| Student Housing Made to Last 2fORM Architecture translates a developer’s interest in sustainability into a quality student housing development How do you . . . design sustainable and durable privately developed student housing? Summary: The Steelhead Townhouses, designed by Eugene-based 2fORM Architecture, are everything privately developed student housing usually isn’t–modern and memorable, thoughtfully designed specifically for students, built sustainably using high-quality materials, and in harmony with the surrounding neighborhood.

The “pleated” windows at the Steelhead Townhouses. Several years ago, developer Dan Neal saw an opportunity opening up in Eugene, Ore. The student population in the city was growing, but housing options were not. The West University neighborhood, just a couple of blocks from the University of Oregon and within walking distance of services and amenities, all of a sudden became the object of second thoughts. “What you have in the West University area is a common pattern,” says Neal, “old housing stock, a haphazard combination of single family homes and older multifamily structures. Most are not well maintained or have design features that are not memorable.” Neal owned some properties in the area and decided to turn them into student housing. The project would require replacing an older structure on a rather narrow lot among other houses and apartment complexes. In dealing with an urban infill site, it was especially important to Neal to come up with a solution with a scale in keeping with the surrounding neighborhood. Following the lead of cities such as Portland and Seattle, and with Eugene becoming denser and more urban, Neal wanted to add an appealing work of Northwest urban architecture to the city. But before he started, he met with the West University neighborhood association to discuss the project. He says the community embraced the opportunity to see old structures replaced with thoughtful design.

The townhouses feature a diverse mix of materials. “This project cost more money than a cookie-cutter box,” he says. “But I don’t want to build something that is not a reflection of my personal values, and I place a high value on excellence in design. We wanted to create something memorable and distinctive.” Because he was interested in building an energy-efficient structure and a building mindful of the surrounding community, Neal was able to take advantage of a Eugene tax exemption program that rewards sustainable development projects in the downtown area. This helped offset the higher costs of premium design and high-quality, durable materials. Designing with residents in mind Speaking specifically about the Steelhead Townhouses, Shugar explains that the design process began with conversations with recent graduates about what makes a good student apartment. That information helped the architect plan the layout of the units, but first he had to deal with the site.

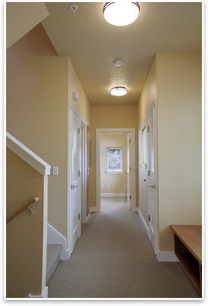

The Steelhead Townhouses in Eugene, Ore. The solution he devised placed the building along one side of the lot. The other side became an open walkway with a low garden wall for seating, which added a communal dimension to the project. “The path had to be more than just a walkway,” says Shugar. “We wanted a community space, regardless of how wide it was, and a place where neighbors could see each other.” Along the same courtyard, each apartment has a semi-private outdoor area next to the front door, which leads into an open space that can be configured as a dining or living area. Shugar decided to isolate the kitchen and placed it beyond this open space on the first floor, toward the back of the unit, to keep food and smells away from the living area. Between the kitchen and the open area is a stairway leading to the two upper levels, each with two bedrooms, one on each side, and a shared bathroom. The second floor also includes a laundry area.

The interiors of the Steelhead Townhouses. Neal wanted the units to have as much natural light as possible and to have spacious and more interesting bedrooms than those in most student apartments. Spaciousness was achieved through vaulted ceilings, 14 feet high at their highest point and nine at their lowest, but also through an unusual window design that added interest and light. “We have angled windows that look like pleats,” Neal says. “They’re visually striking and they let light in from two directions in every single room, so they all seem like corner rooms, even though a small percentage of the bedrooms in the building are, in fact, corner rooms.” The façade of the building is a striking combination of three elements: stucco, cement fiberboard shingles, and corrugated metal. The architect chose a cream-colored stucco base because he wanted a strong material with built-in color close to the ground to weather heavier traffic and frequent moves. The upper third of the building is lined with pre-finished cement fiberboard shingles in a dark brown color resembling wood. And spanning the height of the building, starting on the second floor, are the corrugated-metal-clad bay windows designed to withstand weather conditions with minimal maintenance over time. In addition to the large angled windows, which also afford tenants greater privacy by diverting straight views into neighbors’ units, natural light flows in through a skylight located above the staircase. Shugar designed the units to also allow for cross-ventilation, with bedrooms on both the east and west sides of each apartment. Kelly Rupp was an advertising student at the University of Oregon when he lived at the Steelhead Townhouses. He says his apartment there couldn’t even be compared to other student housing in the area, partly because it was brand new at the time, but also because of its features. Beyond the spacious living room and the convenience of having a laundry center inside the apartment, Rupp says he enjoyed meeting neighbors in the common outside area. Even his one complaint had to do with something he found attractive—the natural daylight that flooded the apartment in the morning sometimes would wake him up. “The windows are huge,” he says. “The apartment gets a lot of light, so I don’t know that I ever really needed to turn lights on during the day.” The architect was able to lower the environmental impact of the townhouses in other ways as well. In addition to allowing plenty of natural light into the apartments, the building features photovoltaic panels, which supply electricity to the units and save on energy costs, and it treats stormwater runoff on site, which lightens the load on the municipal system during times of heavy rains. The building has nine units, eight of which are 1,500 square feet and have four bedrooms and two bathrooms. The remaining unit, located on the south end of the building, is what the architect refers to as a “five plus” unit, and it is nearly 2,000 square feet. This larger apartment has five bedrooms and a sixth space that may be used as a studio (this to accommodate a Eugene city ordinance dating back to the 1970s that doesn’t allow more than five unrelated people living together). The larger unit has three bathrooms and a private deck. Each townhouse has a bike storage unit on the south end of the building, and car parking is also available, with access through an adjacent alley. A long-term investment Materials were chosen with an eye toward durability—custom kitchen and bathroom cabinetry made using formaldehyde-free wood products, granite countertops, paints low in volatile organic compounds, and carpets with recycled content. The only choice that Shugar reflects upon with mixed feelings is the decision to use granite kitchen countertops. The product chosen was shipped from China; it is very inexpensive and also durable, but the architect knows very little about how it’s manufactured. In general, though, Shugar says the approach was to spend a bit more for much better quality. The exterior of the building was designed with the same principles in mind: long life and low maintenance. Neal estimates the useful life of the corrugated sheet metal chosen for the exterior to be about 50 years. The pre-finished cement fiberboard shingle, a product manufactured by Nichiha, a Japanese firm with U.S. headquarters in Georgia, is also very durable. Shugar chose it because it’s a thicker type of cement board shingle than the kind produced by other manufacturers. Also the project includes three window types (fiber glass, aluminum, and aluminum-clad wood), but no vinyl windows. Shugar says he stayed away from vinyl because of the manufacturing processes involved and the longer durability of other products. Clearly the client, a Eugene-native, plans to keep the properties for a long time. Going against a common practice among private developers of student housing, he does not plan to turn the apartments around as soon as major upgrades become necessary, which is why he has invested in durability. “It’s good for the community, good for the students, and good as an investment,” Neal says to make the case. “Who doesn’t want something that lasts?” |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Street Dixon Rick Gets Re-Inspired by the Campus the Inspired America

See what the Communities by Design Knowledge Community

is up to.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “TrailerWrap: A Study in Creating the Habitable Mobile Home,” by Alan Ford, AIA.

See what else the Architects Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

Images courtesy of 2fORM Architecture.