Safdie Gives Kansas City Its Newest Cultural Landmark

The Kauffman Center will complement Holl’s Nelson-Atkins Museum

by Gideon Fink Shapiro

How do you … bring high art into the public realm. How do you … bring high art into the public realm.

Summary: The

new Kauffman Center for Performing Arts designed by Moshe Safdie & Associates,

with BNIM Associates, Associate Architects, aims to reaffirm the

role of the arts in public life, and to give Kansas City, Mo., a

pair of world-class performance venues.

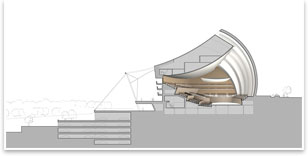

Atop a ridge just south of Kansas City's rejuvenated downtown district, an ambitious 309,000-square-foot, $413 million performing arts center has begun to take shape. When completed in 2011, the Kauffman Center for Performing Arts is likely to outshine its counterparts in many larger cities. Its appearance is striking, its acoustics supposedly flawless. The building's function is both concrete and abstract: Its dedicated 1,600-seat concert hall and 1,800-seat theater must allow the city's symphony, opera, and ballet companies to perform with more refinement and immediacy. In addition, it must inspire public excitement about the arts, attracting larger audiences as well as top performers from around the world.

Following on the heels of Steven Holl Architects' Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art addition, which won a 2008 AIA Honor Award, the Kauffman Center will become Kansas City's next cultural landmark. Yet this sprawling metropolitan area of roughly two million people is distinguished by more than its newfound architectural icons. The city's hilly topography has long set it apart from the flat prairie landscape that surrounds it. The design by Moshe Safdie, FAIA, takes advantage of the hilltop site, which he calls extraordinary because of the broad views it provides, the visibility it affords the new building, and the urban relationships it activates. "The project will be a dramatic portal to connect the downtown with the city," says the architect. Following on the heels of Steven Holl Architects' Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art addition, which won a 2008 AIA Honor Award, the Kauffman Center will become Kansas City's next cultural landmark. Yet this sprawling metropolitan area of roughly two million people is distinguished by more than its newfound architectural icons. The city's hilly topography has long set it apart from the flat prairie landscape that surrounds it. The design by Moshe Safdie, FAIA, takes advantage of the hilltop site, which he calls extraordinary because of the broad views it provides, the visibility it affords the new building, and the urban relationships it activates. "The project will be a dramatic portal to connect the downtown with the city," says the architect.

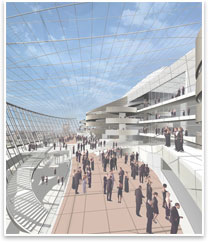

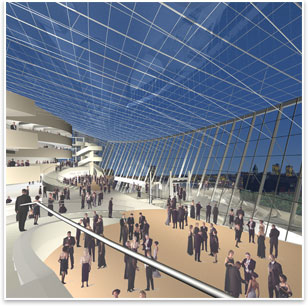

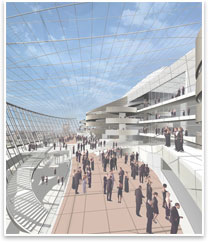

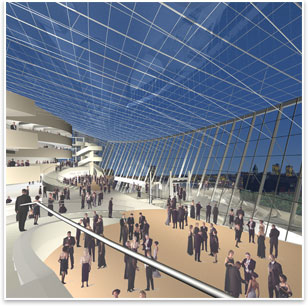

Soaring forms of sculptural quality

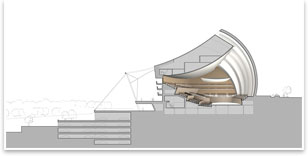

A rippling sequence of vertical arc segments defines the north elevation. Viewed from the central business district, the building's gently curving mass appears to have been sliced at regular intervals, revealing slivers of limestone-colored precast concrete beneath the stainless steel surface. These soaring forms have expressive sculptural quality, but the potential to remake the theater experience is found in the cavernous glazed atrium that runs the length of the south elevation, and in the "vineyard-style" seating plan of the concert hall. Safdie describes the cable-suspended lobby enclosure as a "glass tent" in which the mixing and milling of theater patrons is plainly visible to others outside the building. Jane Chu, the president and CEO of the Kauffman Center, praises Safdie's transparent lobby design as a democratic gesture to allow the whole city to share in the spirit of the arts. It is also a prime example of architecture as advertising: "To be able to see what's going on inside makes people say 'I want to be part of that as well,'" says Chu. Heating and cooling of the lobby will be accomplished through a radiant floor system.

Starting in the nineteenth century, grand performing arts spaces helped define the emerging social and cultural fabric of the modern city. Garnier's 1875 Paris Opéra, for example, embodied bourgeois glamour in Haussmann's Paris. Today, in an age of increasingly sophisticated home theaters and portable media devices, the architectural character of a performing arts center plays a crucial role in enticing patrons. "Going to the theater is an outing," says Safdie, "and it begins with the public space." The airy foyer of the Kauffman Center serves both performance halls simultaneously, creating a social opportunity to see and be seen. Even the acts of arrival and circulation become a kind of ritual performance, as floating staircases lead visitors from one level to another within the vast glass box. Amenities such as the café bar are enfolded within this decentralized ribbon of movement. Starting in the nineteenth century, grand performing arts spaces helped define the emerging social and cultural fabric of the modern city. Garnier's 1875 Paris Opéra, for example, embodied bourgeois glamour in Haussmann's Paris. Today, in an age of increasingly sophisticated home theaters and portable media devices, the architectural character of a performing arts center plays a crucial role in enticing patrons. "Going to the theater is an outing," says Safdie, "and it begins with the public space." The airy foyer of the Kauffman Center serves both performance halls simultaneously, creating a social opportunity to see and be seen. Even the acts of arrival and circulation become a kind of ritual performance, as floating staircases lead visitors from one level to another within the vast glass box. Amenities such as the café bar are enfolded within this decentralized ribbon of movement.

"When you make such exuberant pre-function spaces," Safdie continues, "you can't let down when you enter the main performance spaces." By all accounts the concert hall and theater will have superb acoustics, thanks to the contributions of Dr. Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics. The renowned acoustician also worked on Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and is currently collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron and Jean Nouvel, Hon. FAIA, on new concert halls in Hamburg and Paris, respectively. One thing these concert halls have in common, in addition to having been designed by famous architects, is the use of amphitheater-style seating pioneered in Scharoun's 1963 Berlin Philharmonic Hall, in which the audience fully encircles the stage. Not only does this configuration allow audience members to sit closer to the source of the music, according to Toyota, it also allows them to see each other's faces and thereby experience the performance more communally. "When you make such exuberant pre-function spaces," Safdie continues, "you can't let down when you enter the main performance spaces." By all accounts the concert hall and theater will have superb acoustics, thanks to the contributions of Dr. Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics. The renowned acoustician also worked on Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and is currently collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron and Jean Nouvel, Hon. FAIA, on new concert halls in Hamburg and Paris, respectively. One thing these concert halls have in common, in addition to having been designed by famous architects, is the use of amphitheater-style seating pioneered in Scharoun's 1963 Berlin Philharmonic Hall, in which the audience fully encircles the stage. Not only does this configuration allow audience members to sit closer to the source of the music, according to Toyota, it also allows them to see each other's faces and thereby experience the performance more communally.

For classical musicians, concert hall architecture and acoustics play a huge role in their ability to perform at their best. Mitchell Newman, first violinist and 22-year veteran of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, says that, for instance, Disney Hall has enabled the orchestra to reach new artistic heights. "What we can do in this hall is explore great contrasts in color and dynamics, hear each other clearly, and know that what we produce is heard by the audience as we hear it." For classical musicians, concert hall architecture and acoustics play a huge role in their ability to perform at their best. Mitchell Newman, first violinist and 22-year veteran of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, says that, for instance, Disney Hall has enabled the orchestra to reach new artistic heights. "What we can do in this hall is explore great contrasts in color and dynamics, hear each other clearly, and know that what we produce is heard by the audience as we hear it."

A visual centerpiece within the Kauffman Center concert hall will be the 5,548-pipe organ custom-built by Casavant Freres of Quebec, Canada. Next door in the proscenium theater, Safdie says, thousands of transparent balustrades will glow when illuminated, "almost like the whole room is a chandelier." An adjacent black-box community theater and banquet hall may eventually be realized as planned, pending additional funds. Meanwhile, the facility under construction promises to enhance not only the quality of live performances, but also the aura they project into the city beyond.

|

How do you …

How do you …

Starting in the nineteenth century, grand performing arts spaces helped define the emerging social and cultural fabric of the modern city. Garnier's 1875 Paris Opéra, for example, embodied bourgeois glamour in Haussmann's Paris. Today, in an age of increasingly sophisticated home theaters and portable media devices, the architectural character of a performing arts center plays a crucial role in enticing patrons. "Going to the theater is an outing," says Safdie, "and it begins with the public space." The airy foyer of the Kauffman Center serves both performance halls simultaneously, creating a social opportunity to see and be seen. Even the acts of arrival and circulation become a kind of ritual performance, as floating staircases lead visitors from one level to another within the vast glass box. Amenities such as the café bar are enfolded within this decentralized ribbon of movement.

Starting in the nineteenth century, grand performing arts spaces helped define the emerging social and cultural fabric of the modern city. Garnier's 1875 Paris Opéra, for example, embodied bourgeois glamour in Haussmann's Paris. Today, in an age of increasingly sophisticated home theaters and portable media devices, the architectural character of a performing arts center plays a crucial role in enticing patrons. "Going to the theater is an outing," says Safdie, "and it begins with the public space." The airy foyer of the Kauffman Center serves both performance halls simultaneously, creating a social opportunity to see and be seen. Even the acts of arrival and circulation become a kind of ritual performance, as floating staircases lead visitors from one level to another within the vast glass box. Amenities such as the café bar are enfolded within this decentralized ribbon of movement. "When you make such exuberant pre-function spaces," Safdie continues, "you can't let down when you enter the main performance spaces." By all accounts the concert hall and theater will have superb acoustics, thanks to the contributions of Dr. Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics. The renowned acoustician also worked on Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and is currently collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron and Jean Nouvel, Hon. FAIA, on new concert halls in Hamburg and Paris, respectively. One thing these concert halls have in common, in addition to having been designed by famous architects, is the use of amphitheater-style seating pioneered in Scharoun's 1963 Berlin Philharmonic Hall, in which the audience fully encircles the stage. Not only does this configuration allow audience members to sit closer to the source of the music, according to Toyota, it also allows them to see each other's faces and thereby experience the performance more communally.

"When you make such exuberant pre-function spaces," Safdie continues, "you can't let down when you enter the main performance spaces." By all accounts the concert hall and theater will have superb acoustics, thanks to the contributions of Dr. Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics. The renowned acoustician also worked on Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and is currently collaborating with Herzog & de Meuron and Jean Nouvel, Hon. FAIA, on new concert halls in Hamburg and Paris, respectively. One thing these concert halls have in common, in addition to having been designed by famous architects, is the use of amphitheater-style seating pioneered in Scharoun's 1963 Berlin Philharmonic Hall, in which the audience fully encircles the stage. Not only does this configuration allow audience members to sit closer to the source of the music, according to Toyota, it also allows them to see each other's faces and thereby experience the performance more communally. For classical musicians, concert hall architecture and acoustics play a huge role in their ability to perform at their best. Mitchell Newman, first violinist and 22-year veteran of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, says that, for instance, Disney Hall has enabled the orchestra to reach new artistic heights. "What we can do in this hall is explore great contrasts in color and dynamics, hear each other clearly, and know that what we produce is heard by the audience as we hear it."

For classical musicians, concert hall architecture and acoustics play a huge role in their ability to perform at their best. Mitchell Newman, first violinist and 22-year veteran of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, says that, for instance, Disney Hall has enabled the orchestra to reach new artistic heights. "What we can do in this hall is explore great contrasts in color and dynamics, hear each other clearly, and know that what we produce is heard by the audience as we hear it."