| The New Acropolis Museum: The Parthenon Gets a Bold New Neighbor Bernard Tschumi’s New Acropolis Museum embrace’s antiquity with contextual modesty and strident confidence

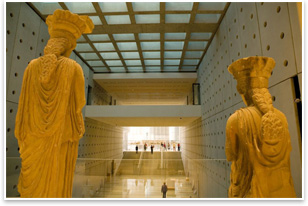

Visit Bernard Tschumi Architect’s Web site. See what the Committee on Design Knowledge Community is up to. 1. The New Acropolis Museum. Photo by Christian Richters. A grand opening Tschumi, says this museum is the “anti-Bilbao” project. “This museum could not exist anywhere else,” he says. “Bilbao is fantastic, but Frank [Gehry] is able to do a variation of that anywhere else. In our case, the museum could not exist without the collection and without the site.” Tschumi also says he was not out to build “another Met.” “I love the Met,” he says. “We all do. But museums are increasingly part of entertainment. This museum is totally the opposite. This museum is about the interaction between the sculptures and the architecture itself, without huge graphic devices and other elements that try to add to the perception. We tried to stay very minimalist, very sober.” The museum’s collection includes 4,000 objects, mostly sculptures, 300 of which are considered major masterpieces. Next month will be the first time the collection will be exhibited together in one place. In shaping the displays, however, the firm did not work with exhibitor designers. “The curated history remains extremely hands-off,” Tschumi says. “The columns and walls are made of concrete, very slightly sandblasted, so they have a very soft feel. The sculptures themselves, which are hard marble, really stand out against a very neutral background.” The new museum sits less than 1,000 feet southeast of the Parthenon. It is surrounded by 75,000 square feet of landscaped gardens and connected to other monuments in the Acropolis through a series of pedestrian walkways.

Tschumi is particularly proud of the conceptual clarity of his design, which follows a chronological order and revolves around the superimposition of three parts. Visitors start at the lower level, where the main lobby entrance is located. The discovery of archaeological remains during pre-construction led Tschumi to incorporate the site into the design. Walking on glass floors, visitors can catch glimpses of the ancient city that once existed at the foot of the Acropolis as they move on up to the mid-section of the museum. The second level, a double-height exhibition space, houses the permanent collection. The pieces from the Archaic period in this section add to the chronological experience. The program peaks at the Classical period in the top section of the building, which houses the Parthenon Gallery. This glass-enclosed, sky-lit space is rotated 23 degrees from the rest of the building.

Tschumi realized the building would have to be oriented a certain way to accommodate the archaeological remains on the lower level. At the same time, he wanted to align the structure with the Parthenon so the sunset and the experience in the new building would match the original experience in the Classical monument. Because the ruins and the Parthenon required different alignments, the upper part of the building, which also has the same dimensions as the Parthenon, is slightly rotated. In the Parthenon Gallery visitors can take in expansive views of the Acropolis and the modern city. The Athens fragments of the Parthenon Frieze have been installed on the rectangular concrete core of the gallery in the same arrangement and orientation they had in the Parthenon. It is Tschumi’s hope and belief that the missing fragments, currently at the British Museum in London, will come back to Athens now that the city has a space to exhibit them. Finally, as visitors move out of the top-floor gallery, the chronology ends back on the second level with pieces from the late-Roman period. In addition to permanent and special exhibit spaces, the museum includes a 200-seat auditorium, a multimedia space, a store, catering venues, a public terrace, and support facilities. Modesty and arrogance meet great challenges Tschumi says his firm was aware of the existence of archaeological remains at the project site when he entered the competition. His design addressed the issue by lifting the structure on more than 100 slender pillars and incorporating the ruins into the museum—not an easy task considering the high risk of earthquakes in the area. “The surprise we encountered was that, as we started construction, inevitably we kept finding more and more ruins, but we were able to expand the original concept,” he says.

But perhaps the greatest challenge of all was to create a structure significant enough to house some of the great monuments of antiquity in curated displays, but humble enough to share the stage with living history. “Greek civilization is the foundation of much of Western culture, and the archeological treasures of the Acropolis collection are a priceless part of our common cultural heritage,” says Erik Ledbetter, director of international programs for the American Association of Museums in Washington, D.C. “This stunning new structure will both conserve those treasures and make them accessible, to the benefit of us all.” Tschumi, of course, is mindful of the significance of the commission: “To be asked as an architect to build something in full view of the Parthenon is just thrilling,” he says. “At the same time, I often say you have to be both very modest and very arrogant to take on such a challenge.” “I guess I am both,” he says with a laugh. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Summary:

Summary: A chronology in three parts

A chronology in three parts “People have talked about it as Deconstructionism,” Tshcumi says. “But I see it as totally logical.”

“People have talked about it as Deconstructionism,” Tshcumi says. “But I see it as totally logical.” Also a challenge was the region’s hot climate, especially when dealing with a collection largely made up of sculptures, which are best appreciated in natural light. Tschumi addressed the issue by making wide use of glass designed to protect the sculptures and keep light flowing through the building. Referring specifically to the use of glass above the archaeological remains, Tschumi praises the role his client, Dimitris Pandermalis, president of the Organization for the Construction of the New Acropolis Museum, played in both guiding decisions and allowing the architect to work with great freedom.

Also a challenge was the region’s hot climate, especially when dealing with a collection largely made up of sculptures, which are best appreciated in natural light. Tschumi addressed the issue by making wide use of glass designed to protect the sculptures and keep light flowing through the building. Referring specifically to the use of glass above the archaeological remains, Tschumi praises the role his client, Dimitris Pandermalis, president of the Organization for the Construction of the New Acropolis Museum, played in both guiding decisions and allowing the architect to work with great freedom.