| In a Knotted Tangle of Freeways and Rail Lines, KAI’s Gateway Transportation Center Ties Together Rail and Bus Transit in St. Louis The long-awaited transit center is a hybrid of scale and form

Summary: The Gateway Transportation Center is a wholly contemporary and modest consolidation of rail and bus hubs in downtown St. Louis. It deals with a challenging and constrained site by emulating and engaging the surrounding transit infrastructure. KAI had to find ways to adapt the form and scale of other transit facilities into the very small scale of the St. Louis bus and train station. St. Louis’s new multi-modal bus and train station is a way forward for midsize American cities brought to task by the lessening economic viability of suburban sprawl and their subsequent neglect of public transit. The St. Louis Gateway Transportation Center sits in the shadow of Theodore Link’s grand Richardsonian Romanesque Union Station, but it offers no historicist-obsessed aesthetic hand-wringing or facile references to 19th century public transit. As a modest and scaled-down transit center housing Amtrak and Greyhound Bus facilities, it offers a consolidated, sorely needed urban amenity to a major city that’s essentially been without a permanent train station for 30 years. The final train pulled out of the grand hallways of Union Station in 1978. (It’s now a retail center and pedestrian mall.) The Gateway station has been in the works in one form or another since then and finally opened in November, delayed after years of site consideration and reconsideration, confused and conflicting project scopes and budgets, and the typically low civic priority that midsize Rust Belt cities have given to rail transit. To make do in the interim, St. Louisans shuffled in and out of a dingy temporary structure derided as the “Amshack” that was hidden under a freeway overpass in downtown St. Louis.

Weave of transit It’s a lot for one building to work around and enough for some to abandon the idea of architecture altogether. “You couldn’t find a worse site for such a regionally recognizable facility,” says Donald Koppy, AIA, vice president and director of architecture at KAI.

KAI’s project is stripped of historicist references to St. Louis’s Union Station and the grand public sphere of 19th century Beaux Arts rail travel, due to site constraints that precluded a typically grand rectilinear solution. This lack of civic presence could be read as a retreat from the democratic ideals of rail transit as a shared cultural experience, but it also directly confronts the atrophy of public transit in St. Louis and other cities like it without shame and with an appropriately scaled and humble $27 million facility. KAI is also working on a similar multi-modal transit building in Milwaukee. Jewel in an alley

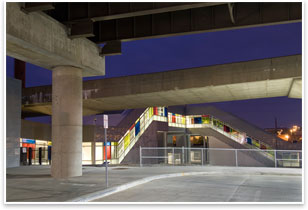

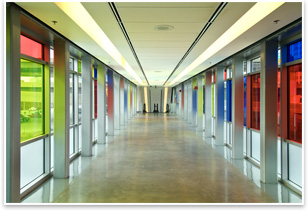

Outside, zinc tiles, white plaster, and multi-colored glass panels are the primary exterior materials on both the main building and the pedestrian corridors that lead to the train tracks. It’s a high-tech machine aesthetic without even a bit of masonry—a dramatic contextual change for St. Louis, which is still defined by brick breweries and the Beaux Arts. The lower section of the main building is largely transparent, with both clear and colored glass panels. This bank of windows extends along the snaking pedestrian corridors that lead to the train tracks in a narrower, focused band. These windows are strongly back lit. “We wanted the color generated from the lighting and glazing to provide luminosity to offset the drabness of the site,” says Pamela Todd, the project’s interior designer with KAI, who worked with its primary designer Brigitte Williams, AIA. Koppy gives the building a decidedly noirish description: “a multicolored jeweled necklace strewn across an alley curb.” The colored glass gives visitors the hard sell on being lively and inviting, but it’s a vast improvement over the grim and gritty gravel lot and shack that made Amtrak passengers wonder where the real train station was. “Before, I felt like I was going to be mugged going there,” says Todd.

The architects at KAI found themselves comparing their small Midwestern train and bus station to Eero Saarinen’s soaringly expressive mid-century Modernist airports. Both the Gateway station and Saarinen’s air travel designs offer similar conceptions of linear dynamic motion. Like Saarinen’s swooping concrete colonnade at Dulles International Airport, the bus and rail station’s canopy reaches skyward from dynamically canted support struts. Koppy even calls the station’s pedestrian corridors “jet ways.” KAI’s train and bus station doesn’t elevate rail travel to a hallowed or romantic place. Instead, it works with its infrastructure-bound site as a piece of infrastructure itself—weaving building through interstate and train tracks with gracious references to some of the best transportation architecture of the 20th century. |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› St. Louis’ Historic Lemp Brewery Converts to Upscale, Mixed-Use Development

› Indianapolis Constructs Greenfield Airport

See what the Public Architects Knowledge Community is Up to.

The AIA’s Rebuild and Renew advocacy plan calls for increased funding of public transit and transportation infrastructure.

Photos:

Images courtesy of KAI Design and Build.

1: The Gateway Transportation Center’s west façade and bus bay canopy.

2: The interior of the bus and train station.

3: The pedestrian corridors duck under freeway exit ramps and over train tracks.

4: The interior of the pedestrian corridors.

5: A birds eye view of the Gateway Transpiration Center.

From the AIA Bookstore: Building Type Basics for Transit Facilities by Kenneth Griffin, AIA (John Wiley and Sons, 2004).

How do you . . .

How do you . . . Had the Gateway station been delayed much longer, it likely would have been a candidate for some of the $8.4 billion allotted for public transit development as part of the federal economic stimulus package signed into law in February. And such a project would have been a model expenditure of taxpayer dollars, and not just because of its formal allusions to the work-a-day pieces of transportation infrastructure that make our cities run. It’s a building that can show a wide swath of Americans how 21st century public transit should operate and look beyond rail’s assumed natural habitat in denser urban typologies along the coasts.

Had the Gateway station been delayed much longer, it likely would have been a candidate for some of the $8.4 billion allotted for public transit development as part of the federal economic stimulus package signed into law in February. And such a project would have been a model expenditure of taxpayer dollars, and not just because of its formal allusions to the work-a-day pieces of transportation infrastructure that make our cities run. It’s a building that can show a wide swath of Americans how 21st century public transit should operate and look beyond rail’s assumed natural habitat in denser urban typologies along the coasts. The building’s massing and relationship to its site is about weaving infrastructure through infrastructure, whether that infrastructure is an inhabitable building or not. There is little civic presence to the building, and from a bird’s eye view, the still scarred and unsodded site seems to be a construction zone where zinc-clad I-beams have been strewn about. In a pragmatic nod to the supremacy of Midwestern automobile transportation, the rail hub isn’t formally privileged over the road. There’s only infrastructure for rail and infrastructure for cars. Project architect Melissa Kreishman, AIA, says KAI’s design is about “fluidity and movement in and around these [infrastructural] objects.”

The building’s massing and relationship to its site is about weaving infrastructure through infrastructure, whether that infrastructure is an inhabitable building or not. There is little civic presence to the building, and from a bird’s eye view, the still scarred and unsodded site seems to be a construction zone where zinc-clad I-beams have been strewn about. In a pragmatic nod to the supremacy of Midwestern automobile transportation, the rail hub isn’t formally privileged over the road. There’s only infrastructure for rail and infrastructure for cars. Project architect Melissa Kreishman, AIA, says KAI’s design is about “fluidity and movement in and around these [infrastructural] objects.”

Little else like it

Little else like it