| Architecture in Second Life Is a World All Its Own A teaching tool, a practice aid, and a game-changing reinterpretation of design—Second Life is leading architecture into a new realm of possibilities

Summary: The online interactive software program Second Life has become an emerging place of architecture research that ranges from a practice tool to an open-ended exploration of design context and expression. Especially in architecture schools, its immersive 3D environments allow users to conceptualize and design a space quickly, thus opening it up for investigation by other users, which allows designers to see how it will be used and how people will circulate through it. Imagine you’re an architecture professor, and you want to demonstrate to your class how the size and proportion of windows in a façade can alter one’s perception of its height. You bring in a model with one set of windows per floor. With a wave of your hand, each window stretches across two levels. With another wave, they are compressed two to a level. The students still aren’t quite getting it, so you fly with them to a full, proportional building you recently designed and you manipulate the window proportions again, while the students hover in the sky at varying distances, taking notes. A fantasy of omnipotence? More like an everyday lesson plan. It’s already happening, in a place called Second Life. Unreal expression

Vasquez de Velasco and his students have been using Second Life to design a hotel and surge hospital with the Las Americas Network. Proving Second Life’s ability to obliterate geographic distances, Las Americas is composed of students from Ball State and from 30 architecture schools across Latin America. Ball State’s Institute for Digital Intermedia Arts and Animation (IDIAA) helped to execute Las Americas design ideas, while BSA Lifestructures, an Indianapolis firm with a robust health-care practice, reviewed and evaluated students’ work. The Las Americas design (which was based on a real site in Indianapolis) is meant to be a luxury hotel that can be converted into a hospital in an emergency. Considering the lack of limits on design expression in Second Life, the hospital and hotel is still quite traditional—a tall, ovular volume with attached “wind sails” that channel air currents. But Vasquez de Velasco says the highest calling of design in Second Life is to create a vernacular unique to this virtual medium. Most spaces in Second Life, he says, are “largely replicas of space in reality. What we have been exploring is to try to develop an environment that not only takes advantage of the conditions of cyberspace or a virtual work, but becomes in part an expression of that kind of environment.” In other words, Vasquez de Velasco’s quest is to design virtual buildings that are less “practical” in real-world terms and express their “virtualness” more transparently. “What we are pursuing here is to be contextual, as we always do with architecture,” he says.

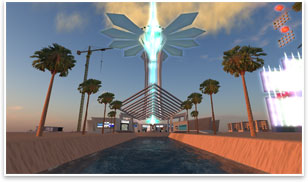

Vasquez de Velasco says Second Life is a good environment for “kinetic architecture” that moves, mutates, and dynamically reacts to the actions of the user. The Las Americas Virtual Design Studio in Second Life is an apt example of simulated architecture with no pretensions of belonging in the real world. Based on a design by College of Architecture and Planning student Brandon Hoopingarner, it’s a pavilion with a (literally) floating gabled roof skeleton and spire. An electric blue bolt of light runs through the spire, topped by floating pentagonal petals. As an open-sourced, virtual setting, Second Life can be used by far-flung multinational design firms to create a workspace “nowhere in particular,” says Vasquez de Velasco. Conversely, designs in Second Life can be experienced more concretely than with other rendering software that may be able to create 3D images, but forces passive viewers to experience space on a predetermined path. The presence of proportionally accurate humanoid avatars allows people to explore, investigate, and experience space before a single shovel has touched the dirt. Very quickly, Second Life users can go from idea conception, to design, to spatial exploration.

This prevents initial designs from being directly translated into other design applications needed to bring a project into construction. One day, say architects familiar with Second Life, there will be an unbroken chain of design stretching from schematic design to construction drawings, all within an open sourced and interactive 3D environment. Second Life collaboration Beaubois sees parallels between Second Life’s digital 3D design capabilities and building information modeling (BIM) software. The collaborative interactivity of Second Life is similar to the Onuma Planning System, a Web-based software program that integrates various other software applications for use in BIM, developed by Kimon Onuma, FAIA, which he’s displayed at various BIMStorm events. “I’m not looking only at virtual environment technology as the be-all-end-all solution,” Beaubois says. “I’m looking at how that works in an office situation where you have word processing, spreadsheets, specifications. I always evaluate software from one point of view: How does this help architects do what they need to do?”

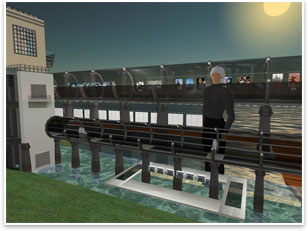

Beaubois regards his work with Second Life as open ended research done in the stead of architects too busy to radically re-evaluate how they design. “I can afford to fail,” he says. “I can try something that doesn’t work.” But is what goes on in Second Life really architecture? Beaubois isn’t sure that it is. As fascinating as questioning the line between simulation and actuality is, everyone knows where the restraints and consequences of reality really begin. “It’s kind of like saying that modifying your avatar is doing plastic surgery,” he says. Which place? Dakota Skies hosted an architecture design competition that was endorsed by AIA North Dakota (Staiger is its executive director.) This competition was inspired by a series of six “chaplets” commissioned by North Dakota artist Marjorie Schlossman. Schlossman asked architects to design small, reverent pavilion-like spaces that she would paint. Staiger (and her Second Life avatar Dakota Dreamscape) opened the competition in November, asking designers to create virtual chaplets. With Linden cash prizes as rewards, she received 11 entries from all over the world, and the four best designs (as judged by Staiger and Schlossman) were on display for a month. The best chaplet designs embrace Second Life’s virtual context wholeheartedly, like the design by avatar “Marcan Aridian”: an ephemeral tiled cube of pink, grey, purple, and white planes with circular portholes cut out—a new exploration of the Modernist maxim of “almost nothing.” Staiger will be opening a new design competition in February called “The Power of Place,” which will explore the influence place has on architecture and culture. But which place? Real or virtual? That doesn’t seem to matter to her. “It certainly is the built environment,” she says. “It’s just in a different realm of the universe.” |

||

Copyright 2009 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› BIMStorm Settles over Alexandria, Va.

› BIM 2011: A Five Year Forecast

› See what the Technology in Architectural Practice Knowledge Community is up to.

Do you know the Architect’s Knowledge Resource?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “BIM in the Architect-Led Design-Build Studio” by James Walbridge, AIA. Walbridge’s article is a case study of a large BIM-designed residential estate project at his firm.

See what else the Architect’s Knowledge Resource has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore:

BIM Handbook: A Guide to Information Modeling, by Chuck Eastman, Paul Teicholz, Rafael Sacks, and Kathleen Liston. (John Wiley and Sons, 2008).

Captions:

Image 1:The Las American Virtual Design Studio in Second Life. Image courtesy of Guillermo Vasquez de Velasco, Assoc. AIA.

Image 2: A chaplet designed by Marcan Aridian. Image courtesy of Bonnie Staiger, Hon. AIA.

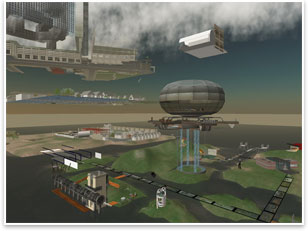

Image 3: Tab Scott reviews model and full scale design of a pedestrian bridge. Image courtesy of Terry Beaubois

Image 4: Tab Scott reviews student construction details in Second Life. Image courtesy of Terry Beaubois

Image 5: Overview of three years of MSU-CRLab work in Second Life. Image courtesy of Terry Beaubois

How do you . . .

How do you . . .

In Second Life, designers don’t have to worry about the forces of gravity, weather, or energy-use criteria (unless they want to). John Fillwalk, IDIAA’s director, says this lack of constraints makes building program the dominant organizing feature for any design. All avatars can fly, so stairs are the first things to go.

In Second Life, designers don’t have to worry about the forces of gravity, weather, or energy-use criteria (unless they want to). John Fillwalk, IDIAA’s director, says this lack of constraints makes building program the dominant organizing feature for any design. All avatars can fly, so stairs are the first things to go. There are limits to Second Life’s design flexibility. Its geometry system of “prims” (short for “geometric primitives”) doesn’t translate well to other design applications. The prims system allows users to select basic geometric shapes (cube, sphere, cone, etc.) and alter them to their wishes. “The geometry in Second Life pretty much wants to originate in Second Life and stay in Second Life, so the pipeline for 3D models is really limited,” says Fillwalk.

There are limits to Second Life’s design flexibility. Its geometry system of “prims” (short for “geometric primitives”) doesn’t translate well to other design applications. The prims system allows users to select basic geometric shapes (cube, sphere, cone, etc.) and alter them to their wishes. “The geometry in Second Life pretty much wants to originate in Second Life and stay in Second Life, so the pipeline for 3D models is really limited,” says Fillwalk. Beaubois anticipates a future when software like Second Life becomes a place where all design and construction professions can collaborate openly and transparently. “Those are the kinds of things I think this technology can support—really good design decisions with the true collaboration that all architecture has,” Beaubois says.

Beaubois anticipates a future when software like Second Life becomes a place where all design and construction professions can collaborate openly and transparently. “Those are the kinds of things I think this technology can support—really good design decisions with the true collaboration that all architecture has,” Beaubois says.