MEMBER-TO-MEMBER

Balancing Design Excellence and Building Security at New U.S. Embassies

by Barbara A. Nadel, FAIA

How do you . . . blend openness and security while serving the high-visibility context of an area rich in history. How do you . . . blend openness and security while serving the high-visibility context of an area rich in history.

Summary: Every new U.S. president has the opportunity to redefine America’s image overseas through foreign policy, public diplomacy initiatives, and appointment of the new secretary of state and ambassadors to represent the president and the American government in the global arena. Much of the work of public diplomacy is conducted within U.S. embassies around the world, along with a host of other important functions, from serving expatriates (Americans living abroad), to issuing visas to host country nationals seeking to visit the U.S.

More than any other civic building type, the location, site, architectural design, and exterior image of embassies often serve as the public face of America to the world in host countries. As iconic symbols of democracy and the American government overseas, embassies have the capacity to foster good will among the international community, and enhance the effectiveness of global diplomacy. It is in the national interest to ensure that American ambassadors and Foreign Service officers are able to conduct diplomacy in safe, secure, well-designed, and efficient environments. Pleasant indoor and outdoor public spaces within embassy buildings and compounds are ideal for hosting conferences, diplomatic receptions, and social gatherings for Americans based in the host country. More than any other civic building type, the location, site, architectural design, and exterior image of embassies often serve as the public face of America to the world in host countries. As iconic symbols of democracy and the American government overseas, embassies have the capacity to foster good will among the international community, and enhance the effectiveness of global diplomacy. It is in the national interest to ensure that American ambassadors and Foreign Service officers are able to conduct diplomacy in safe, secure, well-designed, and efficient environments. Pleasant indoor and outdoor public spaces within embassy buildings and compounds are ideal for hosting conferences, diplomatic receptions, and social gatherings for Americans based in the host country.

In addition to these public diplomatic functions, embassies are also workplaces for American federal employees from various Washington-based U.S. agencies, from law enforcement and finance to commerce and agriculture. These offices, along with a communications component, require secure environments. Collectively, the public, diplomatic, and internal security functional requirements form the programmatic framework for embassy planning and design.

Role of security

Fast-changing global geopolitics and violent terrorist acts against Americans and U.S. assets around the world underscore the need for the U.S. government to provide safe and secure workplaces and residences for American ambassadors, Foreign Service, and government personnel overseas. The post-9/11 environment has heightened awareness that terrorist groups from a variety of countries have developed and practice techniques designed to kill Americans, kidnap ambassadors, and attack U.S. facilities in foreign countries. As a result, the need for site, perimeter, and interior security at U.S. embassies is a fundamental design criterion that must be integrated into site and building design.

After the 1983 Marine Headquarters truck bombing in Beirut, the U.S. government adopted security provisions for blast-resistant design. The 1998 East Africa embassy bombings prompted the U.S. Department of State to re-evaluate security measures at all U.S. embassies. The government determined that many diplomatic facilities did not meet security standards and were vulnerable to terrorist attack. Since then, and after the events of September 11, 2001, blast protection techniques, perimeter security, technology, and operational procedures have been refined and implemented at domestic and overseas U.S. facilities. After the 1983 Marine Headquarters truck bombing in Beirut, the U.S. government adopted security provisions for blast-resistant design. The 1998 East Africa embassy bombings prompted the U.S. Department of State to re-evaluate security measures at all U.S. embassies. The government determined that many diplomatic facilities did not meet security standards and were vulnerable to terrorist attack. Since then, and after the events of September 11, 2001, blast protection techniques, perimeter security, technology, and operational procedures have been refined and implemented at domestic and overseas U.S. facilities.

The September 2008 suicide bomber attack on the U.S. Embassy in Sana’a, Yemen, was unsuccessful. The terrorists were unable to breach the secure perimeter, and Americans inside the compound were not harmed, an indication that the design, technology, and operational procedures worked as intended.

Berlin embassy: balancing design excellence and security

Design excellence and providing secure facilities for American personnel working overseas need not be incompatible. The new U.S. embassy in Berlin, designed by Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners with Gruen Associates, illustrates how sensitivity to site, architectural design, sustainability, local building codes, and security criteria can be skillfully merged in a single facility.

In September 2008, at a one-day symposium at the Berlin embassy, participants toured the indoor and outdoor public areas and workspaces and interacted with Americans and Berlin-based journalists on their impressions of the building and its response to the site and design criteria. In September 2008, at a one-day symposium at the Berlin embassy, participants toured the indoor and outdoor public areas and workspaces and interacted with Americans and Berlin-based journalists on their impressions of the building and its response to the site and design criteria.

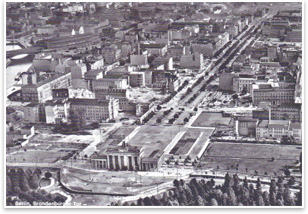

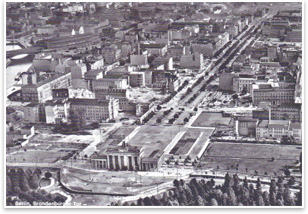

Located at the historic Pariser Platz, in the former East Berlin, the new U.S. embassy is adjacent to the enduring symbol of Germany, the Brandenburg Gate, completed in 1791, and across from the haunting, orderly field of concrete slabs that compose the Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe, designed by Peter Eisenmann, FAIA, completed in 2004.

The new Berlin embassy supports the civic character of Berlinís governmental district with a strongly contextual modern building. The complex history of the U.S. presence on the site dates back to 1931. In 1995, almost six years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the U.S. Department of State organized a design competition for the new Berlin embassy. The 1998 East Africa bombings and re-assessment of embassy security criteria caused delays of six years. After considerable diplomatic efforts from the U.S. ambassador, the Berlin mayor, and U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, planning for the U.S. embassy resumed in 2002.

Under the direction of the Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations (OBO), the new embassy is a rethinking of the original 1995 competition-winning scheme to meet new security, site, and programmatic conditions. The design compliments the stately Brandenburg Gate and responds to several landmark urban elements near the site, including the grand scale of the re-occupied Reichstag with Norman Foster‘s celebrated dome, the Federal Government complex, and nearby commercial development of Potsdamer Platz. East of the embassy is the DZ Bank, designed by Frank Gehry, FAIA. The French Embassy by Christian de Portzamparc lies directly across from the square.

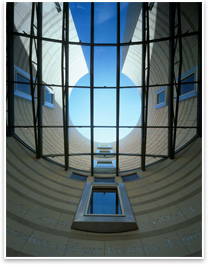

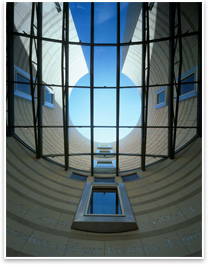

“The U.S. Embassy in Berlin offers an understated response to its historically charged context. Instead of making the entire building into a landmark-or a palace-we preferred to use a loft building archetype as a site for landmark elements like the rooftop Lantern and the carved-out Rotunda. These features are scaled to speak to the Brandenburg Gate‘s Quadriga and the Reichstag Dome, both lighter sculptural forms that animate the skyline around Pariser Platz,” says John Ruble, FAIA, Partner at Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners, recipient of the 2006 AIA Architecture Firm Award. “The U.S. Embassy in Berlin offers an understated response to its historically charged context. Instead of making the entire building into a landmark-or a palace-we preferred to use a loft building archetype as a site for landmark elements like the rooftop Lantern and the carved-out Rotunda. These features are scaled to speak to the Brandenburg Gate‘s Quadriga and the Reichstag Dome, both lighter sculptural forms that animate the skyline around Pariser Platz,” says John Ruble, FAIA, Partner at Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners, recipient of the 2006 AIA Architecture Firm Award.

The British Embassy, around the corner from the U.S. Embassy and adjacent to the renowned Hotel Adlon, was designed by British architect Michael Wilford, who attended the Berlin symposium and led a tour of the building, which includes a rich array of public art, open space, natural light, colorful workplaces, and secure working environments. To accommodate security criteria and standoff, or building setback, the street in front of the British embassy is closed to vehicular traffic.

“The design of the U. S. embassy in Berlin strikes a fine balance between respect for the historic context of Pariser Platz and establishes a vivid U.S. presence,” observes Patrick W. Collins, architectural design branch chief at OBO. The embassy plan provides a secure compound with a traditional courtyard building, which combines a large area of contiguous floor space for maximum flexibility, with narrow building depths to enhance the use of natural light. The courtyard offers a quiet central green in the midst of Berlin’s busiest tourism district and provides a popular venue for community events, such as the annual July 4th barbeque.

According to Ruble: “The embassy was to some extent designed from the inside out. On the outside it directly expresses its interior program, with the representational Lantern of the ambassadorís conference room, and below that the trellised windows of the open, day-lit loft spaces that provide the staff with a 21st century workplace.” According to Ruble: “The embassy was to some extent designed from the inside out. On the outside it directly expresses its interior program, with the representational Lantern of the ambassadorís conference room, and below that the trellised windows of the open, day-lit loft spaces that provide the staff with a 21st century workplace.”

The Berlin embassy’s strong focus on providing a quality workplace is reflected in the building’s green agenda. Energy efficiency and daylighting is enhanced by passive solar shading using window trellises that reduce heat gain and allow filtered light at other times. Rainwater collection and planning to replace built areas are aligned with Berlin’s urban guidelines. Building construction is consistent with current standards for certification by the U.S. Green Building Council. A partial green roof is planted with sedum. The rooftop garden is adjacent to the elegantly designed conference room, with spectacular views of the iconic 18th century Quadriga sculpture atop the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, and the Berlin skyline.

“All too often the public focuses on the exterior of U.S. embassies abroad and judges them credible or not. Embassy buildings serve as the representation of America’s presence abroad. But the organization of the interior presents America at work—how our nation’s government performs its activities abroad. For a nation to truly project greatness, we must have efficient, effective, and collaborative government. The interiors of U.S. embassies should ensure that efficiency and collaboration are facilitated by the organization and design of the building,” observes Ambassador Donald S. Hays (Ret.), who was involved with the interior planning of the new Berlin embassy.

Public art in the Berlin embassy is an outstanding collection of works by Christo, Alexander Calder, Andy Warhol, and a vibrant wall drawing by Sol LeWitt. These contemporary works by acclaimed American artists reinforce American values of advancing art and architecture at home and around the world.

The Back Story:

In September 2008, the AIA formed the 21st Century Embassy Task Force, composed of architects, engineers, and landscape architects familiar with embassy design; former ambassadors; and representatives of the American Foreign Service Association, American Academy of Diplomacy, U.S. General Services Administration, OBO, and the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies. The goal of the task force is to take a fresh look at the way embassies are planned, designed, and built and revisit some of the policies surrounding embassy design over the last eight years, when Standard Embassy Design (SED) was in place at OBO. As task force chair, article author Barbara Nadel, FAIA, collaborated with Andrew Goldberg, Assoc. AIA, senior director of AIA Federal Relations, to develop and distribute a survey to the task force members in October 2008.

In November 2008, the AIA hosted a half-day symposium to facilitate an open dialogue among OBO, design professionals, and the diplomatic community. Discussions included whether OBO should implement a Design Excellence and Peer Review program for embassies, modeled on a similar program in place at GSA for federal buildings. The response to the survey and the symposium has been enthusiastic and positive, Nadel reports.

In mid-December 2008, as the AIA representative to the U.S. Department of State OBO Industry Advisory Panel, Nadel will present several high-level recommendations and a report documenting the task force findings. These recommendations will be considered for implementation by OBO Ad Interim Director Richard J. Shinnick, his successor in the Obama Administration, along with the presumptive secretary of state, New York Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton.

If accepted by OBO and the State Department, the recommendations and report of the AIA 21st Century Embassy Task Force will represent the first steps in providing new leadership opportunities for architects to advance design excellence, sustainability, and secure facilities, and to showcase contemporary American artists in new U.S. embassies around the world.

|

How do you . . .

How do you . . . More than any other civic building type, the location, site, architectural design, and exterior image of embassies often serve as the public face of America to the world in host countries. As iconic symbols of democracy and the American government overseas, embassies have the capacity to foster good will among the international community, and enhance the effectiveness of global diplomacy. It is in the national interest to ensure that American ambassadors and Foreign Service officers are able to conduct diplomacy in safe, secure, well-designed, and efficient environments. Pleasant indoor and outdoor public spaces within embassy buildings and compounds are ideal for hosting conferences, diplomatic receptions, and social gatherings for Americans based in the host country.

More than any other civic building type, the location, site, architectural design, and exterior image of embassies often serve as the public face of America to the world in host countries. As iconic symbols of democracy and the American government overseas, embassies have the capacity to foster good will among the international community, and enhance the effectiveness of global diplomacy. It is in the national interest to ensure that American ambassadors and Foreign Service officers are able to conduct diplomacy in safe, secure, well-designed, and efficient environments. Pleasant indoor and outdoor public spaces within embassy buildings and compounds are ideal for hosting conferences, diplomatic receptions, and social gatherings for Americans based in the host country.

In September 2008, at a one-day symposium at the Berlin embassy, participants toured the indoor and outdoor public areas and workspaces and interacted with Americans and Berlin-based journalists on their impressions of the building and its response to the site and design criteria.

In September 2008, at a one-day symposium at the Berlin embassy, participants toured the indoor and outdoor public areas and workspaces and interacted with Americans and Berlin-based journalists on their impressions of the building and its response to the site and design criteria. “The U.S. Embassy in Berlin offers an understated response to its historically charged context. Instead of making the entire building into a landmark-or a palace-we preferred to use a loft building archetype as a site for landmark elements like the rooftop Lantern and the carved-out Rotunda. These features are scaled to speak to the Brandenburg Gate‘s Quadriga and the Reichstag Dome, both lighter sculptural forms that animate the skyline around Pariser Platz,” says John Ruble, FAIA, Partner at Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners, recipient of the 2006 AIA Architecture Firm Award.

“The U.S. Embassy in Berlin offers an understated response to its historically charged context. Instead of making the entire building into a landmark-or a palace-we preferred to use a loft building archetype as a site for landmark elements like the rooftop Lantern and the carved-out Rotunda. These features are scaled to speak to the Brandenburg Gate‘s Quadriga and the Reichstag Dome, both lighter sculptural forms that animate the skyline around Pariser Platz,” says John Ruble, FAIA, Partner at Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners, recipient of the 2006 AIA Architecture Firm Award. According to Ruble: “The embassy was to some extent designed from the inside out. On the outside it directly expresses its interior program, with the representational Lantern of the ambassadorís conference room, and below that the trellised windows of the open, day-lit loft spaces that provide the staff with a 21st century workplace.”

According to Ruble: “The embassy was to some extent designed from the inside out. On the outside it directly expresses its interior program, with the representational Lantern of the ambassadorís conference room, and below that the trellised windows of the open, day-lit loft spaces that provide the staff with a 21st century workplace.”