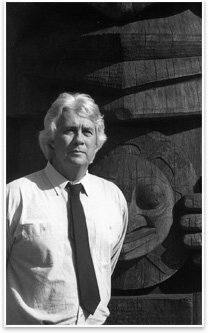

Johnpaul Jones, FAIA Johnpaul Jones, FAIA

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: Johnpaul Jones, FAIA, is a founding principal at the Seattle firm Jones and Jones Architects and Landscape Architects. Jones was the lead design consultant for the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. His firm also was the landscape architect for the San Diego Zoo, one of the first zoos in the U.S. to place animals in cageless, natural habitats. Jones was the recipient of the AIA Seattle Medal of Honor in 2006, and his firm was the inaugural recipient of the ASLA Firm Award in 2003.

Education

I graduated in ’67 from the University of Oregon School of Architecture in Eugene with a bachelor of architecture. It was a good school for me because it mixed a lot of art and architecture and the fields of landscaping and planning and interiors all together.

How did you become interested in architecture?

I was pretty good at art, and when I was in middle school I took a lot of drafting and art classes. When I got to high school they didn’t have any of that, but they had an architectural drawing class and they asked me if I would be interested in that. I did it, and I think that’s what piqued my interest. Then I got a job my last year in high school with an architect in the San Francisco Bay area—Los Gatos—and that really was a turning point.

I’m from Oklahoma and I’m part American Indian. I’m Choctaw and Welch. My dad was born in Wales. My mother is Choctaw. We migrated to California when I was in junior high school. People often ask how I got to Oregon. I was pretty good at sports, too, and I had a water polo scholarship to Berkeley, but I couldn’t get in because I didn’t have a foreign language. I wasn’t very good at that. Somebody recommended the University of Oregon and the architect I was working for said: “We’ll fly you up there to see if you can get in.” And I did.

Paying it forward

The firm I worked for was called Higgins and Root in Los Gatos. Chester Root earned his master’s from Harvard, and the person who had sponsored him there told him: “You don’t have to pay me back—but you sponsor somebody else somewhere.” So he, as part of his sponsorship, sponsored me for a couple of years at the University of Oregon and helped me with my tuition and books and all that stuff. It was nice to have that kind of architectural support in the early days going to architecture school.

In turn, I’ve sponsored an American Indian architect at the University of Oregon and mentored here in Seattle at the University of Washington three, maybe four, years.

Why did you begin your own practice?

Jones and Jones is a true joint practice of landscape architects and architects. There are 50 of us—we’re 25 landscape architects and 25 architects, so we really believe in that. You can do a lot of wonderful things with land and landscape and placing buildings in the environment, both in their urban environment and in the country. I joined my other two partners, who are both architecturally trained, but one of them is a landscape architect. Grant Jones got his master’s at Harvard, and then Ilze Jones got her architecture degree but she’s really a wonderful planner, so it’s a nice joint practice. I love that. In the ’60s, they were saying that architects needed to change and be more adaptive and flexible and get out of the ivory tower. So it was nice to run into the other two Joneses [ed. note: none of the three Joneses are related] and be able to start the practice.

Jones and Jones is commonly recognized for designing spaces that are strongly connected to place. How would you describe your firm’s design philosophy?

I think it’s just being very respectful of the land, the place where the project is located, and the people. That’s kind of general, but from my heritage in the Choctaw world, what I try to do is look at what I call the four worlds that were passed on to me from my mother and grandmother. What that means is that on any project we’re doing, we look at the natural world around us: What’s the topo and the land and the trees, but also where it’s located. What are the equinoxes and the solstices, and where’s the sun at various times in the year? Then we look at the animal world: Who’s using this besides us? We look at the spirit of the place. The last thing we look at is the human world—how to pass on the knowledge and how to make it welcoming.

We all really believe in those strong worlds and put it into our design and planning work, both in landscape and architecture. Consequently, we were the first firm to start putting zoo animals in natural habitats, and we’ve been doing that for 30, 40 years. Our philosophy is really to look at the history of the land. What was it doing before we showed up to do a project here and how does it affect the water quality and the people around it? So it’s wonderful to practice with landscape architects.

You’re probably best known as the lead design consultant for NMAI. For what project would you like to be remembered?

That project. There are close to 500 tribes in North America, and they’re all very different. It was wonderful working on that project to be able to create something that was organic and Indian enough that it could speak to all those diverse people. Centering it on those four worlds I was telling you about really allowed all these diverse tribes to be able to relate to that project and feel like they were welcome in Washington, D.C. And that, I would say, is the paramount thing.

The second one, I would say, is working in the zoological world and creating places that are humane for animals in zoos that had been just terrible. It’s wonderful to be on the forefront of making that what it is now, where people are teaching and learning about the environment and the animals rather than just seeing the animals pace back and forth. I think those two things are key.

What do you think is a good way to get more American Indians interested in architecture as a profession?

It’s a good field for Indian kids to get into. I belong to the American Indian Council of Architects and Engineers, and there are maybe 40 or 50 of us in the whole country. We work at trying to encourage the architecture schools to recruit more. Many kids end up in other programs, but we try to sponsor and provide scholarships at select universities because we don’t have a lot of money. It’s a really good field, and a lot of it has to do with intuition. After you’ve learned everything, your intuition tells you what to do and helps you.

I think Indian kids have a lot of strength in that area that they can put into it, so I’ve been encouraging and mentoring and trying to help as many Indian kids get into the architectural design field. But they represent a very small percentage in the architectural community right now. Some schools, such as the University of Oklahoma, have made direct efforts to recruit Native kids. The University of New Mexico also is doing that, so there are a few schools that really see the value of it.

We have a program here in Seattle where a couple of Native designers go out and talk to the younger kids and bring them in and show them architectural work. I’m going down to the University of Oregon in early December to talk to a bunch of Native kids from the state of Oregon who are interested in getting into architecture school. I think there are 20 or 30 of them. Very few will ultimately want to do it, but it’s an opportunity just to show them what we do and how we can benefit their own tribe and society in general. It’s a good opportunity to help that way and increase the Native involvement in architecture.

What can architects do to help American Indian communities?

A lot. There’s a lot to be involved in. Most people think every tribe has a casino. A good number of them do, and they have some cash flow. Most of them have a constitution that they have to follow and they have to put money into social services, education, cultural stuff, and housing, and all that. There are a lot of opportunities for architects in the Indian community now that have never been there, and they’re just getting under way. So I think good design, planning, and sustainable goals for projects in Indian communities is something that tribes want. They want to get out of the poverty levels that they’ve been in, so it’s a good field for architects to help in. And they need help, so there’s plenty of work.

Final thoughts?

When I give talks, I often say that this country has a great Native American architectural heritage. It’s magnificent, and not a lot of people know that. In architecture school, you usually have to take a year or two of the history of architecture. When I did it in the ’60s, they didn’t even talk about Native American architecture at all. That’s a shame, because there are some wonderful, magnificent native structures and villages still existing here in this country that would be good for people to know about. I’d like to encourage including those Native structures as something that’s worth studying in schools of architecture and having more people learn about. |

Johnpaul Jones, FAIA

Johnpaul Jones, FAIA