Diversity:

What the Numbers Tell Us Summary: In June 2004, AIA Convention delegates resolved to strengthen the demographic diversity of the design profession, including “access to the profession and career advancement for minorities, women, and other groups.” Honoring that resolution, AIArchitect offers a series by renowned architecture author Stephen A. Kliment, FAIA. In this first installment, Kliment sets the stage for his upcoming examinations of trail-blazing African-American architects and their work. Below is a synopsis of the article. For the full text, click on the PDF link located in the column on the right. “Merely engaging in high-minded debates about theoretical

future reductions while continuing to steadily increase emissions

represents a self-delusional and reckless approach. In some ways,

that approach is worse than doing nothing at all, because it lulls

the gullible into thinking that something is actually being done,

when in fact it is not.”

African-American architects licensed to practice in one or more of the states at press time numbered 1,558, of whom 185 are women. This represents a mere 1.5 percent of the architects registered in the U.S., or about an eighth of the 12.1 percent African Americans represented among the U.S. population as a whole. As one would expect, these practitioners range across a vast spectrum of firm size, ownership, employment status, gender, personal history, location, self-appraisal, and aspirations. Some came from humble beginnings, grew up attending all-black schools, were discouraged from embracing architecture as a career, yet persevered through architecture school and into practice. Others, from more privileged backgrounds, found their way with fewer bumps but not without facing various forms of discrimination in school and beyond. Some own their own firms; others have achieved full partnership in large, majority-owned firms. Still others have found careers in public service—permanently or as a stepping stone to private practice. A small contingent—a little more than 100—teach full-time in architecture schools; many taking on supplemental design projects.

Black architects as individuals |

||

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Dr. Sharon Sutton, FAIA: Diversity Matters

› EVP/CEO Christine McEntee: “I’m Listening”

› Demographic Data Analysis Affirms Anecdote and Perception

A full-text,

printer-friendly version of this article is available.

Download the PDF file.

Captions

1. “The Builders,” by Jacob Lawrence, 1947. Photo:

The Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation/Art Resource, N.Y.

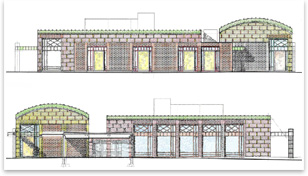

2. For the Africana Studies and Research Center expansion by Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbott, principal architect Ralph T. Jackson, FAIA, uses texture and color to establish the program’s identity and presence on the Cornell campus.

In upcoming episodes of this series, there will be much for black and majority architects to feel good about, the author assures us. Look for a parade of significant innovative work by an array of quality-conscious black practitioners, along with stirring stories on how some had a smooth path to success, some overcame steep professional, social, financial, and personal hurdles. In November, expect a look at fascinating black trailblazers. Subsequent episodes will explore African identity and historic African architectural roots that counterbalance the dominant Eurocentric teaching and criticism. The reader will also get a glimpse at the critical role patrons and patronage hold in shaping the prospects of black architects, the role of black women in the profession, and the three great drivers that if applied will shape the prospects of the African American architect for the better for generations to come.

Note: Where figures designate only African Americans, it is so stated.

Otherwise, the term minorities includes

Asian and Hispanic/Latino groups and a breakdown was not available.

Al

Gore’s objection to lots of talk but little action has

something in common with the urge to say the right things about the

challenges facing African-American architects. But all this does

little actually to advance the cause of greater opportunity for black

architects.

Al

Gore’s objection to lots of talk but little action has

something in common with the urge to say the right things about the

challenges facing African-American architects. But all this does

little actually to advance the cause of greater opportunity for black

architects. The mood today

The mood today