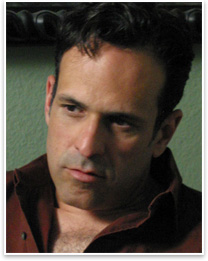

| Michael Selditch

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: Michael Selditch worked for 14 years as an architect, first in the office of Mitchell/Giurgola, then as a sole practitioner. In the early 1990s, he used his skills as an architect to switch his career to television and film. Among the shows he has worked on are Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, Project Runway, Gourmet’s Diary of a Foodie, and 30 Days. His newest television series is Architecture School, a six-part reality show that follows Tulane School of Architecture students as they design and build homes for struggling New Orleanians. The Sundance Channel series began on August 20 and airs at 9 p.m. on Wednesdays. Summary: Michael Selditch worked for 14 years as an architect, first in the office of Mitchell/Giurgola, then as a sole practitioner. In the early 1990s, he used his skills as an architect to switch his career to television and film. Among the shows he has worked on are Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, Project Runway, Gourmet’s Diary of a Foodie, and 30 Days. His newest television series is Architecture School, a six-part reality show that follows Tulane School of Architecture students as they design and build homes for struggling New Orleanians. The Sundance Channel series began on August 20 and airs at 9 p.m. on Wednesdays.

Education

I went to Penn State for my undergraduate degree in their architecture program and then to University of Pennsylvania, where I got an MArch.

Current read

I just finished reading Infidel by Ayaan Hirsi Ali. She’s amazing! What an incredible story this woman has. It’s unbelievable. It makes me as a white male in America feel like a jerk that she has gone through what she has. It makes me feel like I had it so easy.

Why did you become an architect?

When I was about 10 years old, a neighbor of ours was having a house built, and I used to go with them every week to watch the progress. I was completely fascinated by it and, from looking at the drawings, I would try to imagine what the house would be. From that time, even as a little kid, I felt like I was able to imagine what it would look like and the whole thing just really excited me. I was absolutely certain at that time that was what I wanted to be, so it still surprises me to this day that that’s not what I’m doing.

From architect to film maker and TV producer

I was always a big fan of Louis Kahn—especially from going to Penn—and all of the great architects who studied with him, like Romaldo Giurgola. I always loved his work. When I left Penn in ’85, it was a really good time to get a job. The economy was good, and I wound up getting a job in Giurgola’s office and worked there for almost four years. I met a lot of great people there, including Michael Manfredi and Marion Weiss of Weiss/Manfredi, who are really close friends of mine and are doing amazing things in their firm. It was a great time and I really enjoyed what we were doing.

After four years of working in the office, I was starting to get a bit disillusioned with the profession of architecture. Architecture itself I still loved. It was the profession that was frustrating to me. I had done some things on my own—little things on the side—and working with contractors and having them get between me and the client was very frustrating. Actually, getting things built the way I saw them was a constant frustration, so I took a break from the office world and started teaching.

I spent my entire last year at Mitchell/Giurgola going out to Los Angeles for meetings once a week. I decided that I was going to try to teach, applied for schools in New York and in L.A., and got a job at Woodbury University in Los Angeles. The school was about 100 years old, but their architecture program was only six or seven years old at that time, so I was only the second full-time faculty member. There, I met some key people with whom I’m still very close. One of them is Stan Bertheaud, an architect from New Orleans who was also teaching at Woodbury. He and I later became writing partners. He was studying screenwriting at USC in addition to teaching architecture, so he was on that verge of changing professions as well.

That was one of the things that opened my eyes to a second love that I always had, film, which I also had as a child. When I was 10 years old I was making little Super 8 films. That was always there with the architecture but it never overpowered the architecture because I was so certain that I wanted to be an architect. When I came back to New York, I started teaching at Pratt at the School of Visual Arts and freelancing more doing my own projects. Then I started designing sets at the same time, because I had this film interest and I thought: “How can I get in there?” I didn’t want to go back to school because I still had a lot of school loans and thought: “I can design sets.” I started designing sets for little independent films and that was how I learned the process of how you make a film.

So, there was a period of 10 years when I was dabbling in both, still freelancing doing house additions and stuff on my own, still teaching architecture, and doing this set stuff. In that process, I made my own short film and then another short film, and so that was growing at the same time.

Why did you leave the profession?

In ’99, which was my 10th year of doing both and trying to find a place in the film industry, I got a job producing a television show that was a documentary or docu-drama. Now we’d call it a reality show. That was enough of a job that I could actually make a living on it and not have to rely on doing architecture projects. I don’t think I realized how unrealistic that is to have two careers going full force at the same time, but there was so much in me that I just didn’t want to let go of it.

I think what I learned as an architect and in architecture school guides me as to how I do what I do now. For example, the idea of looking at the enormous big picture and the tiny little detail at the same time and being able to switch your brain back and forth between those things is something that I really developed in architecture school, and it’s something that a lot of people in industries like this aren’t always able to do. They can’t focus on all of those different scales at the same time.

Right now, I’m running a 13-episode series. I’m the executive producer on it so I’m running the whole thing: the pre-production, the production, and the post-production. It’s very parallel to architecture with the design phase, doing the construction documents, and then the construction. As an architect, I’m able to think about the whole building and the little handrail detail at the same time, and in this case think about the whole series and how each episode has to be consistent—even though I have 10 producers out in the field with 10 different cameramen—and then have the end result feel like it’s from the same television series. It’s a very similar way of thinking.

What inspired you to create Architecture

School?

Stan Bertheaud and I have always talked about writing something with architects or architecture school in it, because we both taught so much—and the whole process in school is something that people don’t really know about. But even more so, I think that I was always frustrated that people don’t really get what architects do. I was constantly surprised when I was an architect when people just didn’t understand what an architect did. It seemed so obvious to me. When I got into television I always felt like architecture was not portrayed anywhere. In movies it’s always inaccurate. The guy’s always really glamorous, driving a great car, and never seems to work. It’s so inaccurate. It’s always been a desire to somehow fuse the two fields together and let people really see what architects do. Why do we need them? What do they think about? What’s important to them and that sort of thing.

Stan and I always talked about a bunch of different projects, and one of them was simply to do a documentary where we went into a school and watched what they did. I found myself in Sundance’s office a couple of years ago having a standard meet-and-greet and something that we were talking about made me think about the architecture discussion that Stan and I always had. On the fly, I pitched this architecture school idea and they were really into it.

We looked at eight different schools and talked about the pros and cons of each. Sundance is very much into having a strong social message to their projects, so we went towards the New Orleans idea. Reed Kroloff was the dean at that time at Tulane. What a great guy Reed is! He immediately saw the potential of this. I think there was a trust element because I was an architect. If it were just some producer coming in from L.A. saying “we want to do a show on your school” I don’t know if they would’ve been quite as open as they were. But I said to them: “This is not a reality show, it’s a documentary. It’s not about kids sitting around in a hot tub or fighting with each other and kicking them off the island.” It all came together and just made a whole lot of sense. I’ve been in this television world for almost 10 years now, and it’s the project that I’ve always known I needed to do—and do from a place of understanding the subject matter really well.

Advice for architecture students

It’s funny. When we were in school, we heard the same things that I heard these kids talking about at Tulane all these years later. I remember the first day of school hearing our dean say don’t expect to be making any money. I remember at the time thinking I don’t care. I love this. Money doesn’t matter to me. And I’m hearing it from these kids today. It’s the same thing. Well, when you get out in the real world and have to pay your bills, it gets to be a drag when you feel that you should be making more money in what you’re doing. It becomes really frustrating.

I think the advice that I would give these kids is to try to get out there and work as early as you can while you’re in school. Try to get some of the experience that’s more like when you’re a working architect than in school. School is great. School is 99 percent about design. In the real world, architects maybe are spending 5 percent of their time on design, and then there’s a whole bunch of other real things that have to be dealt with like running a business, getting clients, or dealing with a client, which you don’t have in school either. Not that you shouldn’t do it that way, but that you understand that there’s a huge difference between being in school and being in practice.

|