|

Hurricane Research Center: The Anti-Levee

What if flexible disposability rather than brute force is the best way to build on hurricane coasts?

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

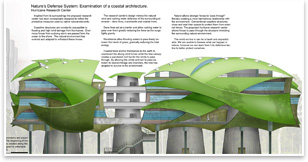

Summary: The Hurricane Research Center looks to native flora for its hurricane-resistant features. Instead of forming a purely oppositional relationship with hurricane winds and flooding like typical levees and concrete bunker hurricane labs, this building is designed to accommodate damaging winds while still maintaining a baseline level of structural integrity. Like leaves on a tree, sections of the research center are designed to rip off without compromising vital structural and shelter elements. These sections are elevated by trunk-like concrete columns anchored to the ground by steel cable roots that lift them above the coastal flood plain. Summary: The Hurricane Research Center looks to native flora for its hurricane-resistant features. Instead of forming a purely oppositional relationship with hurricane winds and flooding like typical levees and concrete bunker hurricane labs, this building is designed to accommodate damaging winds while still maintaining a baseline level of structural integrity. Like leaves on a tree, sections of the research center are designed to rip off without compromising vital structural and shelter elements. These sections are elevated by trunk-like concrete columns anchored to the ground by steel cable roots that lift them above the coastal flood plain.

How do you ... design a hurricane-resistant building that uses biomimicry to respond and give to natural forces?

Brian White, Assoc. AIA, created his Hurricane Research Center in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when debates swirled about repopulating destroyed regions of the Gulf Coast. The massive disaster stung Americans’ confidence in our ability to protect vulnerable coastal regions from flooding and questioned the sustainability of doing so. Clearly, the argument went, hurricanes, people, and the built environment that comes with them cannot co-exist. White’s project responded to this debate by disregarding these underlying assumptions. Brian White, Assoc. AIA, created his Hurricane Research Center in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, when debates swirled about repopulating destroyed regions of the Gulf Coast. The massive disaster stung Americans’ confidence in our ability to protect vulnerable coastal regions from flooding and questioned the sustainability of doing so. Clearly, the argument went, hurricanes, people, and the built environment that comes with them cannot co-exist. White’s project responded to this debate by disregarding these underlying assumptions.

Instead of defending structures against hurricanes with levees and lockbox concrete construction, his Hurricane Research Center responds and gives to natural forces while still retaining a basic structural integrity. It moves beyond the all-or-nothing protection offered by levees and wind-proof bunkers by using pre-fabricated components that mimic natural systems to minimize hurricane damage.

Leaves in the wind

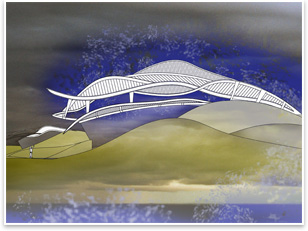

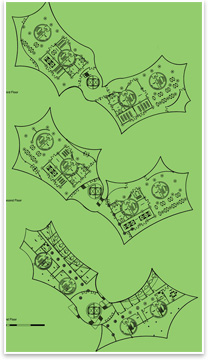

The research center’s hypothetical site is Daufuskie Island in South Carolina, a small barrier island near Hilton Head where hurricanes are common. White’s complex of buildings is composed of a four-level main research center and two separate auditoriums that are nestled into beachfront sand dunes.

The main building is composed of a steel frame with a canvas-like tensile fabric stretched over it. This shape and structure emulates oak tree leaves, with asymmetrical arcs and triangular points. Like tree leaves, these sections are meant to break off during a severe hurricane without sacrificing the building’s overall integrity. Non-vital laboratory functions, like classroom and meeting spaces and extraneous labs, are located here, while fundamental systems and shelter components are located within the building’s four concrete column legs. The main building is composed of a steel frame with a canvas-like tensile fabric stretched over it. This shape and structure emulates oak tree leaves, with asymmetrical arcs and triangular points. Like tree leaves, these sections are meant to break off during a severe hurricane without sacrificing the building’s overall integrity. Non-vital laboratory functions, like classroom and meeting spaces and extraneous labs, are located here, while fundamental systems and shelter components are located within the building’s four concrete column legs.

There are no oppositional walls of concrete or masonry, standing against the tide on only the strength of their mortar, and the research center’s shape is organically aerodynamic; an abrupt formal change from hurricane lab construction as it exists today.

“These things aren’t supposed to resist hurricane forces,” says White, an architect with FreemanWhite in Charlotte. “If you’ve seen people design hurricane-resistant buildings, they try to make gigantic concrete blocks. I found that in nature that’s not what happens. In nature, the elements transform themselves to allow forces to pass through them. They’re not trying to be a wall in front of a tidal wave.”

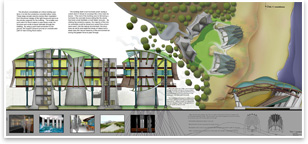

A series of open steel tubes provide natural ventilation, daylighting, and hurricane pressure equalization. As White points out, the reasons roofs are often sheared off of houses in hurricanes isn’t only because of high wind speeds. These high wind speeds lower the air pressure outside of the house, sucking roofs upward. Running the height of the building, the tubes emerge out of the top of it with concave triangular solar scoop panels that channel sunlight into the facility, which radiates via perforations in the tube throughout the building’s interior. As hurricane winds blow over the tubes, these perforations allow air pressure to equalize between the inside and outside. A series of open steel tubes provide natural ventilation, daylighting, and hurricane pressure equalization. As White points out, the reasons roofs are often sheared off of houses in hurricanes isn’t only because of high wind speeds. These high wind speeds lower the air pressure outside of the house, sucking roofs upward. Running the height of the building, the tubes emerge out of the top of it with concave triangular solar scoop panels that channel sunlight into the facility, which radiates via perforations in the tube throughout the building’s interior. As hurricane winds blow over the tubes, these perforations allow air pressure to equalize between the inside and outside.

Tied to the ground

Four lighthouse-like concrete columns that White calls “trunks” lift the building up 30 feet in the air to protect its facilities from floodwaters and to allow winds to pass over, under, and through it, if the leaf-like sections break off. The building’s most critical systems and spaces (HVAC, plumbing, vital lab spaces, and emergency shelter) are contained in these volumes.

White chose this as the building’s final line of defense after looking at pictures of devastated neighborhoods in the Gulf region. Invariably, some of the only structures left standing were concrete water towers. He sees these parts of the building as a nucleus for recovery efforts. “If people are trapped they can come there and use it as a shelter, or after the fact they can use it as a base camp,” White says.

Both the concrete trunks and steel and fabric building envelope are to be prefabricated, White says, which should aid in rapid reconstruction. Because the island is geographically isolated (it’s inaccessible by car or truck) and sparsely populated, the labor and transportation savings that prefabrication affords is even more significant.

Each “trunk” is anchored by steel cables modeled after tap roots, which reach deep into the earth. Like plant roots, they allow an amount of sway and tension without snapping.

The two clam shell-shaped auditoriums that sit in front of the research center are tucked into sand dunes and designed to be deluged with water, flooding them completely or even ripping off the roof.

A compromise A compromise

The Hurricane Research Center is willing to compromise with nature, to make concessions and sacrifices for the sake of the entire building, but ultimately to stand pat against hurricane-force winds and water. It’s not governed by the binary succeed/fail measures that every simple levee and wall operates by; an appropriate response considering how levees have become a symbol of infrastructural failure after the post-Katrina flooding of New Orleans.

White’s model, which he says could be adapted into an entire building typology, lessens its environment impact by taking advantage of the efficiencies of off-site construction and gains further sustainability bonuses from its use of natural light and ventilation. It’s a fitting set of eco-friendly priorities for a building that incorporates biomimicry as exhaustively as the Hurricane Research Center. And the conceptual ideas about nature it suggests are just as progressively green. A levee asserts that nature can be subordinated. The Hurricane Research Center suggests that it must be respected. |