| Oslo Opera House: Center Stage for Urban Revitalization

by Tracy Ostroff

Contributing Editor

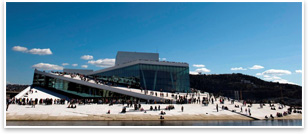

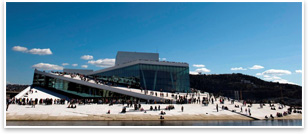

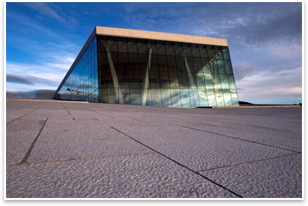

Summary: The architecture of the Oslo Opera House has met with universal critical acclaim for its form and its function. Snøhetta’s Modern design for the building, which rises from the Oslo fjord, is inspired by the Norwegian landscape and is a magnet for the droves of people who come to enjoy not only the performances inside, but the spectacular building itself. It was the architect’s intent to create a space to give new life to the community—a barren, portside warehouse district—through a monumental building from which all other development would flow. Summary: The architecture of the Oslo Opera House has met with universal critical acclaim for its form and its function. Snøhetta’s Modern design for the building, which rises from the Oslo fjord, is inspired by the Norwegian landscape and is a magnet for the droves of people who come to enjoy not only the performances inside, but the spectacular building itself. It was the architect’s intent to create a space to give new life to the community—a barren, portside warehouse district—through a monumental building from which all other development would flow.

How do you ... revitalize a neighborhood with a monumental building?

Snøhetta Director and Partner Craig Dykers says the Norwegian firm reflected deeply about what it would mean to create a monumental building. “We created a holistic experience where the memory of the object includes a journey as much as a destination.” The firm’s building, chosen in an anonymous selection process, is meant to be touched or otherwise engaged, the architect notes, imprinting on its user some version of its sculptural form. Rather than traditional monuments that are disengaged from the user experience, this building encourages the visitor to feel as if they possess it. Snøhetta Director and Partner Craig Dykers says the Norwegian firm reflected deeply about what it would mean to create a monumental building. “We created a holistic experience where the memory of the object includes a journey as much as a destination.” The firm’s building, chosen in an anonymous selection process, is meant to be touched or otherwise engaged, the architect notes, imprinting on its user some version of its sculptural form. Rather than traditional monuments that are disengaged from the user experience, this building encourages the visitor to feel as if they possess it.

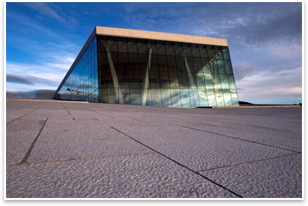

“When you step on something you feel like you own it. You feel that it is yours,” Dykers says. The monumental character is particularly reflected in its roofscape, which offers a horizontal and sloping plane reminiscent of ski slopes for visitors to ascend up to views of the city, the mountains, and the fjord. The dramatic expression and its openness and accessibility allow visitors to traverse the many terraces of the elevated urban plaza. It’s clad in white stone and, according to the architects, provides a holistic and symbolic character to the building while also allowing for a variety of experiences as one moves past and through it.

As the largest single cultural-political initiative in contemporary Norway, and financed with taxpayer dollars, it was important, Dykers says, that people feel connected, both to the building and with the community that surrounds it and the nation beyond. Unlike the Sydney Opera House, which is faced to the harbor, the architects oriented the Oslo Opera House back toward Bjorvika. Still, on top of the roof, in addition to city views, there are vistas that do not connect to the town, but only to the sky or the fjords, or pieces of nature, with each view a characteristic of the whole country.

In the house In the house

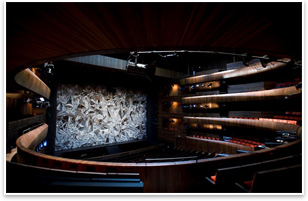

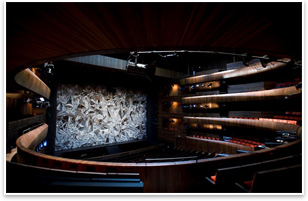

The building, of course, is also a national opera house, a state-of-the-art venue that had to respond to complex engineering challenges and a rigorous design program. The building rises like a glacier from beneath the waters of the Oslo fjord. It sports 36,000 white marble slabs and aluminum on its exterior. Described in the architect’s statement as a “factory,” it has 1,100 rooms grouped in a number of sections. The front-of-house public areas are located in the building’s western section, with access from the area nearby the city’s train station. These include the main foyer, a large horseshoe-shaped performance auditorium with 1,350 seats for the national opera and ballet, and a small, flexible auditorium with 400 seats.

In contrast to the white marble on the outside, the warm oak wood on the inside acts as part of a transition of materials that passes through both the exterior and interior of the building. Dykers likens it to being within the shell of a walnut, “as though a fruit has been peeled and the seed exposed.” He also notes that the wood acts as a resonance material. “In the mind’s eye, the wood assembles the sound in the same way as a violin or guitar chamber,” he says. “In this way, the wood subconsciously connects the function of the building with the material.”

“Many operas, especially national operas, focus almost entirely on the characteristics of the public space. In this opera we have focused on both the back and front of house areas. We have given dialogue to the interaction of these two worlds in the expression of the exterior where the functional forms and the sculptural identities interact. We hope the building will be a joy to work in as much is it an exciting experience for the theatergoer,” Dykers notes.

Incredible response Incredible response

Liv-Beate Skavdahl, the Oslo Opera House director of marketing, says: “This really is a big success. More than 300,000 people have come to visit us [50,000 came in the first week alone], mainly walking on the roof. People did not realize it would be this great and this magical.”

She also reports that the new building, “totally changed the people’s view of architecture and the importance of the arts in Oslo, and now in Norway.” She says that in a survey commissioned after the building opened, 55 percent of Norwegians say the opera is for everyone. That’s compared to 5 percent who responded positively in a previous study. She also noted that 57 percent of people say they feel welcome in the new opera house; that it is no longer the province of the “culture elite,” a term that has negative connotations for many in the Nordic country.

“This is going to be the inspiration for the redevelopment of the entire area,” Skavdahl says of the 415,000-square-foot space, which also includes bars, restaurants, and shops that draw visitors regardless of whether performances are taking place. With the King of Norway opening the facility in April amidst a gala celebration, and the tremendously positive response, there is news that two other museums—the Munch Museum and the city’s Stenersen art museum—as well as the national library, will be located in the district. City planners are also routing a tunnel under the fjord to better connect the east and west sides of the city.

Take and give Take and give

When a unanimous jury awarded Snøhetta first prize in the design competition for the new Oslo Opera House, they said: “The design takes from the city and gives back to the city.” With its roof and park-like amenities, where people do tai-chi in the morning and swim in the afternoon, the Oslo Opera House is an example of how a beautifully designed building can become the cornerstone of urban revitalization.

To some, the Bjorvika district was an unlikely candidate for one of the world’s premier performing arts venues. In the U.S., the area might be considered on the “wrong side of the tracks,” with the Oslo equivalent of the tracks being the centuries-old Askerhus Castle, where, to its west, spreads a thriving community—full of wine bars, galleries, restaurants, and other businesses. Now people think to take their Sunday walk, a cherished ritual in Norway, to the other side of the city, Skavdahl notes, to their opera house.

Skavdahl says that a forward-thinking politician advocated the site with the notion that if the city and national officials put the opera house in Bjorvika, a lot of other good things would follow. There are now plans for shops, corporate buildings, and housing development. Perhaps as important, Skavdahl says, since the politicians, public, and designers have embraced the opera house as a key driver of the eastern side of Oslo, the debate about other projects has become much more civil and elevated. “Usually, finding the site is a long, long process, but suddenly it is a good climate. It will be a lot easier in the future to work out these differences.”

No master plan No master plan

The theory behind the Oslo Opera House and the redevelopment of the Bjorvika region is that all future development would have to react to the building, facilitating an organic process that would spur other revitalization efforts, Dykers says. “This is really a revolutionary way of working.” Although he says it may be a risky way to work, it is no more risky than other master plans where there is no complete buy-in.

He is a little overwhelmed by the positive reaction to the building. “Good will goes a long way,” he says of his firm’s efforts to give back to the community a space all could enjoy, not just those who go with ticket in hand for a performance. (Those tickets, Skavdahl reports, are 80 percent sold out through the end of the year, ahead of expectations.)

As the first element in the planned transformation of Bjorvika, the building has indeed given new life to the community and to the ecology of the area. If nature is an indication of what the future holds for this ballet and opera, there is good reason for optimism. Dykers says the day the building opened, two swans appeared. The next day two ducks also graced the landscape, in an area where there had previously been very little wildlife.

Of their building, the architects say in their project description: “The dividing line between the ground ‘here’ and the water ‘there’ is both a real and a symbolic threshold. This threshold is realized as a large wall on the line of the meeting between land and sea, Norway and the world, art and everyday life. This is the threshold where the public meets the art.” |

Summary:

Summary: Snøhetta Director and Partner Craig Dykers says the Norwegian firm reflected deeply about what it would mean to create a monumental building. “We created a holistic experience where the memory of the object includes a journey as much as a destination.” The firm’s building, chosen in an anonymous selection process, is meant to be touched or otherwise engaged, the architect notes, imprinting on its user some version of its sculptural form. Rather than traditional monuments that are disengaged from the user experience, this building encourages the visitor to feel as if they possess it.

Snøhetta Director and Partner Craig Dykers says the Norwegian firm reflected deeply about what it would mean to create a monumental building. “We created a holistic experience where the memory of the object includes a journey as much as a destination.” The firm’s building, chosen in an anonymous selection process, is meant to be touched or otherwise engaged, the architect notes, imprinting on its user some version of its sculptural form. Rather than traditional monuments that are disengaged from the user experience, this building encourages the visitor to feel as if they possess it. In the house

In the house Incredible response

Incredible response Take and give

Take and give No master plan

No master plan