6/2006

Building becomes an exhibition itself

by Tracy Ostroff

The California Academy of Sciences (CAS), with its unique suite of exhibitions, including a planetarium, aquarium, and natural history museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, is seeking to become the city’s “greenest” building, a feat the natural history museum turned to Pritzker Prize-winning architect Renzo Piano to help realize. The Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), in collaboration with San Francisco-based Chong Partners, is unifying the academy’s 12 separate buildings into a single 410,000-square-foot structure to provide more space on a smaller footprint and return one acre of land to the park. A hallmark of the project is its two-acre undulating “green” roof, just one of the many sustainable strategies the team is implementing with a goal of a U.S. Green Building Council LEED®-Platinum rating.

“It is like cutting a piece out of the park, lifting it up, and then putting the museum under so we wouldn’t lose any green space,” says Olaf de Nooyer, an RPBW partner. With the natural history museum as a client, de Nooyer says, “the green idea was something that we thought had to be integrated into the design.”

“It is like cutting a piece out of the park, lifting it up, and then putting the museum under so we wouldn’t lose any green space,” says Olaf de Nooyer, an RPBW partner. With the natural history museum as a client, de Nooyer says, “the green idea was something that we thought had to be integrated into the design.”

“One of the first things that Renzo Piano tried to do is something about the scattered amount of buildings in the park to make it into one institute. The way he proposed to do that was with a big roof that would cover all the different buildings. That’s something that has been part of the design almost from day one,” de Nooyer says.

With buildings damaged in the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, when it first started the project, the academy was considering a less significant renovation. But that plan was soon nixed by a feasibility study. “Apart from being expensive, the layout of the different buildings built at different times with different floor levels was a nightmare to make something workable.” The project’s path was also determined with a question posed by CAS Executive Director Patrick Kociolek. “I went to the board and proposed that we ask what a natural history museum is in the 21st century.”

Sustainability: from bottom to top

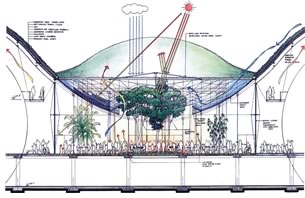

The curving lines of the green roof echo the rolling hills of the San Francisco landscape. “But the shape of the roof is not just formalism—the façade is actually a reflection of parts of the program in the building. The three large undulations reflect the planetarium on the exhibit floor—a very large sphere, which is a rain forest exhibit—and the third part is a Neoclassical vault of the Steinhart aquarium, which is one of the pieces of the old academy we are restoring in this new institution,” de Nooyer says. The floor plan consists of four rectangular buildings on which the roof sits. The three-story cruciform open space is the main exhibit floor.

The roof will be an education area itself, with its nearly 2 million native California plants and other habitats. A 30-foot-wide glass canopy, supported with a steel structure, has photovoltaic cells integrated in the glazing, which will be able to generate 5 percent of the energy for the building. Glass curtain walls and operable circular skylights will allow natural light into the interior exhibit space. Daylight will illuminate the exhibits and the building—except for some of the most sensitive collections and specimens—will be naturally ventilated. The four, three-story facades have louvers and operable windows and sunshades that open and close based on weather conditions, the position of the sun, and the temperature in the building.

De Nooyer and Kociolek say the scientists and researchers are excited about having natural daylight and fresh air in the labs, although they expressed some reserve about exposing the collections and exhibits to UV rays and humidity. “The main part of the exhibits at the academy work well with daylight and natural ventilation,” de Nooyer says. Kociolek agrees, with the caveat that they will be monitoring conditions to make certain.

Kociolek says the academy sees the building as an exhibition. He writes that the academy will use about 50 percent less energy than California codes allow a standard building to consume, with some of the energy derived from clean, renewable sources to reduce pollution. “Besides saving energy,” Kociolek notes, “daylighting and natural ventilation systems will make the interior of the building more comfortable. The design team is also carefully selecting healthy, non-toxic building materials that do not cause indoor air pollution. An improved indoor environment will not only benefit staff and visitors; the academy can also expect higher levels of productivity and lower levels of absenteeism.”

Teasing out green

Teasing out green

The new academy is one of 10 pilot green building projects that the San Francisco Department of the Environment is planning for its public architecture program. “Sustainability and conservation have long been part of the academy’s history, and currently part of our ethic. In the early stages of the project we knew that’s what we wanted to do, but we were less sophisticated about things like LEED and the U.S. Green Building Council,” says Kociolek. De Nooyer says the architects brought to the team the notion of green design.

Kociolek notes that only after a fair amount of design work had gone into it did the academy bring the Rocky Mountain Institute in for an evaluation. At the end of the appraisal they found the building was high into LEED-Gold certification. “We weren’t looking at their checklist; we weren’t trying to identify all the points you can get. We were just saying that every place in the design that we can, let’s make sure that we are thinking about green strategies. Then, much later, we thought about ways to organize the team and communicate in a very nice and succinct way that this building is being designed as a LEED Platinum building.”

With green so integrated with the design, Kociolek notes, it became difficult to differentiate between the two. He points to the roof as an example. “You see this undulating roof that was a metaphor for this very organic place of science and nature within this rolling landscape. But it also facilitates the natural ventilation on the museum floor. So do you want to charge that to being green or is that just a design element?”

The green design, Kociolek says, has the Board’s support. “When we learned that we were high in the Gold, and there could be a few moves that we could make that would get us to Platinum, the board was enthusiastic about going to Platinum. And as you could imagine for a project of this scale, we have been through a couple of value engineering exercises. Never once has the board wanted to move back from Platinum as a goal. And we have just as many business-oriented and bottom line-oriented trustees as any other board.”

The 21st-century natural history museum

Kociolek says the academy wanted a flexible and changeable museum. “In the 20th-century, maybe even the 19th-century model of natural history museums, it was almost as if people were searching for these eternal truths that you would then embody in a capital project that would last decades . . . for us this is almost the antithesis of science. Science is not static, it’s not creating dogma. It’s about new hypotheses, new data, and the dynamic nature of science. So what we wanted to try to do is to work with people who are used to creating architecture that supports change.”

Rather than traditional exhibit consultants, the academy hired professionals from the retail area to design exhibitions that are changeable and foster synergy between the building and the displays. “We said to Renzo we need this building to multi-task, we need it to change and flex for our scientists, and for different types of programming. We told this group of designers we want to incorporate change into this program frequently. That allows us to get that new scientific information, those new discoveries on the public floor, and to create new ways to invite people back to the museum.”

Piano was particularly drawn to the commission because it melds its function as a natural history museum with a place for research and scientific inquest. “There are institutes where the museum is a museum—just a public event, but where the actual research is done somewhere else. The academy is particular in that a third of their area is research based. They also have a huge collection of specimens from all over the world. It’s incredible what they have, it’s an incredible experience to see it, and it will also be very nice to show it to the public,” de Nooyer says.

Piano was particularly drawn to the commission because it melds its function as a natural history museum with a place for research and scientific inquest. “There are institutes where the museum is a museum—just a public event, but where the actual research is done somewhere else. The academy is particular in that a third of their area is research based. They also have a huge collection of specimens from all over the world. It’s incredible what they have, it’s an incredible experience to see it, and it will also be very nice to show it to the public,” de Nooyer says.

“Those three things together—part exhibit for public, part research, and part collection of the academy are the three main program points of the academy. One of the design ideas for us was to make a building that was like an onion,” de Nooyer explains. “People go into the building and peal off layers and understand things about nature. But they also see parts of the ‘back-of-house,’ the part of the academy that has collected all the specimens and has done all the research. This is one of the strings that pulls through the design.”

Homage to past . . . forward to future

Instead of rehabilitating the old buildings, the designers are paying homage to the old academy by keeping the façade of the African Hall and rebuilding the front of the Steinhart in the spirit of the past, keeping some of the familiar landmarks of the old academy for the community.

The architects started off making the curving roof out of wood beams in an attempt to use natural materials, but that design did not work for city fire regulations. “So we changed it into a steel structure which will be visible,” de Nooyer says. “We’ll combine the steel with concrete for the interior and exterior facades. The three-story-high walls surrounding the exhibits are made of architectural concrete with a very fine reveal system on top of it. We also are using holds in the concrete as a support system for exhibits on these walls. Steel and concrete are the two main materials, along with glass, which we use in the facades. Over the piazza is extra wide glass. We are looking for a very transparent building emphasizing continuity between inside and outside. You can look through the building from one side to the other.”

All these changes are good for the public and the researchers. “There’s another environment that you have to take into account as well, and that’s the intellectual environment,” Kociolek says. “In the old facility, if you took a string and stretched it to the two most distant points in the old building you ended up in scientists’ offices. So at a time when we really need our intellectual capital to come together and create spaces to interact and create dialogue, we had our intellectual capital pushed aside. There is this other environment that this new building is trying to foster and create, which is an intellectual environment that creates places and collaboratories (laboratories to collaborate) and places for scientists to come together, versus the old building, which made us struggle to get that to happen.”

The new building will also be a place of public learning. “The concept of the ‘natural history museum’ originated in the 19th century, a time before the discovery of DNA, atomic energy, modern medicine, before the use of electricity, and long before we realized the wealth of the earth’s biodiversity or the threat of global climate change,” Kociolek says. “We are building a new facility that will enable us to explain science in a way that everyone can understand, that brings the public into the process of discovery and exploration.”

Copyright 2006 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

The architects also worked closely with Arup design consultants on many facets of the project. Arup’s scope of work on the project included structural and building services engineering (mechanical, electrical, plumbing), fire engineering; acoustics consulting, LEED™ sustainability consulting, sustainability advice and design review; and benchmarking and life cycle analysis."

The new academy is scheduled to open in Golden Gate Park in late 2008.

Renzo Piano was named by Time magazine as one of “The People Who Shape Our World,” in the artists and entertainers category. He was the only architect on this year’s list of 100 individuals.

![]()