Over the River, Under the Atrium: Gaylord National Harbor

Gensler and Gaylord Hotels invite you down to the river with their own window on the Potomac

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

Summary: Designed by the Washington, D.C., office of Gensler, Gaylord’s National Harbor Hotel and Convention Center modulates its scale and massing to respond to its site on the Potomac River in Maryland, just south of the District of Columbia. It’s organized around a massive, dual-leveled central atrium that contains literal recreations of historic Chesapeake Bay architecture and landscaping.

How do you ... design a hotel and convention center that draws its massing from its relationship to an adjacent river and contains a central atrium that organizes its circulation and spatial orientation?

For a building so concerned with precisely controlled and programmed interiors, the new Gaylord National Harbor Hotel and Convention center just outside the Washington, D.C., beltway expends a great amount of effort in projecting the visitor’s attention and experience outside the hotel to the Potomac River it borders. From back to front, the building changes its massing, scale, and landscaping to lead guests visually to the riverbank in terraced steps. The building’s vast glass and steel vaulted atrium is a telescopic projection that eyes the river as intently as a Colonial-era navigator in a clipper ship might have done. For a building so concerned with precisely controlled and programmed interiors, the new Gaylord National Harbor Hotel and Convention center just outside the Washington, D.C., beltway expends a great amount of effort in projecting the visitor’s attention and experience outside the hotel to the Potomac River it borders. From back to front, the building changes its massing, scale, and landscaping to lead guests visually to the riverbank in terraced steps. The building’s vast glass and steel vaulted atrium is a telescopic projection that eyes the river as intently as a Colonial-era navigator in a clipper ship might have done.

This 230-foot, dual-leveled expanse of glass and steel offers something for people on the outside peering in to look at as well. Visible from the connecting arterial highway, it dominates its site just south of the District of Columbia on the eastern bank of the Potomac River. The task for its architects at Gensler was to moderate its monumentality. “The trick for us was to take this large, monumental building and always have the scale work from a distance and work from close up, so as you get closer up you ought to find more interest and a little bit deeper story,” says Jeff Barber, AIA, co-manager of the Gensler office in Washington.

At its largest scale, this terracing approach is most obvious as the building steps down from 18 stories to 7 stories moving toward the river. An 11-story volume of hotel rooms sits in the rear. “It’s massed in a way that tries to get the scale to be appropriate from the water on up,” says Barber.

Two thousand hotel rooms wrap around both atriums, from the sides and the rear, making the $865 million, 2.5 million-square-foot Gaylord National Harbor the largest combined hotel and convention center on the East Coast. Below the steel and glass atriums, the hotel volumes are primarily constructed of precast concrete and rough-cut stone at it their base. The shoebox-shaped convention center connects to the complex on the south side of the 42-acre site and also faces the river to the west. Two thousand hotel rooms wrap around both atriums, from the sides and the rear, making the $865 million, 2.5 million-square-foot Gaylord National Harbor the largest combined hotel and convention center on the East Coast. Below the steel and glass atriums, the hotel volumes are primarily constructed of precast concrete and rough-cut stone at it their base. The shoebox-shaped convention center connects to the complex on the south side of the 42-acre site and also faces the river to the west.

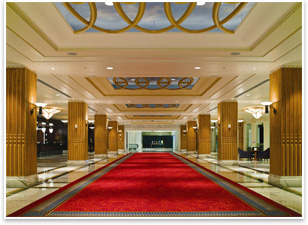

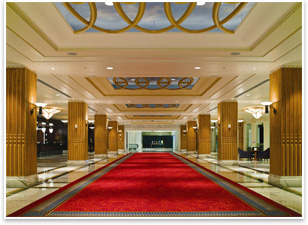

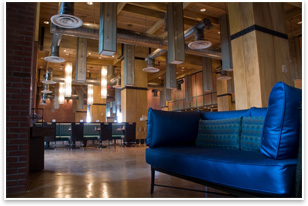

The main entrance to the hotel is on the north side of the building, which opens into lobby space and the hotel’s reception and check-in area. This area (and much of the hotel and convention center) is decorated in Colonial and maritime motifs: golds, navy blues, dark woods, dour 18th century portraits, and smoky white Italian marble.

Literal history

At the rear of the check-in and reception area are open views to a terrace that leads to the centerpiece of the atrium experience: a “Colonial” village Gensler calls its “town square.” It’s a densely packed mix of indoor park space, retail, and dining. It’s organized symmetrically around a central fountain surrounded by a manmade stream. Flora native to the Chesapeake Bay region (such as ash, ficus, and ferns) are planted throughout. Two full-scale Colonial-era houses, one of red brick and the other clapboard, sit on each side of the atrium along a brick paved pedestrian street. Restaurants, bars, lunch counters, and a spa surround the town square. One, a seafood restaurant, sits next to an artificial dock and wharf where visitors can dine “outside” year round without the bother of opportunistic seagulls or the smell of rotting seaweed. Press materials about the hotel and convention center talk of creating “sensory connections to the cultural heritage of the Chesapeake region.”

This is a starkly literal approach to incorporating geography, history, and culture into a building’s parti, and it’s quite Gaylord’s style. At Gaylord Palms outside of Orlando, the hotel and convention center developer stepped outside of local geography to fuse together three different set pieces. There, guests can stroll through an Everglades swampscape, a tropical island Key West recreation, and a Colonial Spanish village styled after St. Augustine, Fla. At Gaylord Opryland, guests can ride and an indoor Delta flatboat through a tour of its atrium. This is a starkly literal approach to incorporating geography, history, and culture into a building’s parti, and it’s quite Gaylord’s style. At Gaylord Palms outside of Orlando, the hotel and convention center developer stepped outside of local geography to fuse together three different set pieces. There, guests can stroll through an Everglades swampscape, a tropical island Key West recreation, and a Colonial Spanish village styled after St. Augustine, Fla. At Gaylord Opryland, guests can ride and an indoor Delta flatboat through a tour of its atrium.

Barber says Gaylord encourages this kind of historicism. “It doesn’t have to be a negative thing,” he says. “They want the experience for their guests to be pretty direct.”

Amie Gorrell, a spokesperson for Gaylord, says that these literal historical and natural set pieces are appealing to rushed conference attendees who don’t get a chance to leave the hotel and convention center complex.

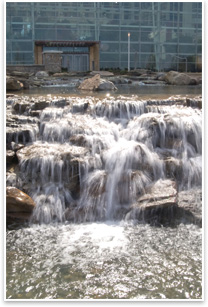

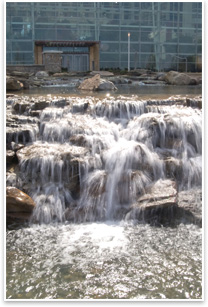

The terraced progression of the space under the atrium also leads visitors’ gazes and bodies to the river. Above the check-in lobby and reception area is another terrace, which sits under the taller of the two atriums and offers the widest views up, across, and out of the atrium. From here, the transition to the more intimate scale of the town square looks drastic. But, from the wide views of the upper and lower terraces to the colonial village, the scale of views and orientation is gradually reduced until the human-scaled town square comes into focus and visitors are led to the glass wall that looks out to the river. Once outside, guests are further enticed to the waterfront by following a stream that leaves the atrium and flows towards another fountain on the riverbank. This fountain is the centerpiece of terraced landscaping that also steps down towards the river, gradually modulating access to the Potomac. The terraced progression of the space under the atrium also leads visitors’ gazes and bodies to the river. Above the check-in lobby and reception area is another terrace, which sits under the taller of the two atriums and offers the widest views up, across, and out of the atrium. From here, the transition to the more intimate scale of the town square looks drastic. But, from the wide views of the upper and lower terraces to the colonial village, the scale of views and orientation is gradually reduced until the human-scaled town square comes into focus and visitors are led to the glass wall that looks out to the river. Once outside, guests are further enticed to the waterfront by following a stream that leaves the atrium and flows towards another fountain on the riverbank. This fountain is the centerpiece of terraced landscaping that also steps down towards the river, gradually modulating access to the Potomac.

Making sense out of space

A glance upward at the atrium roof reveals a rich mix of textures and weights, some thick and brawny, others lithe and airy. The primary structural members are broad arching bow-truss tubes that span the north side of the atrium to the south side. Rods suspended below the bow trusses connect at each end to prevent the tubes from sagging. The vertical glass wall on the front face of the atrium is supported against wind loads by thinner, vertical bow trusses. An orthogonal grid holds the flat glass panels in place.

The hotel’s two elevator cores stand sentry on either side of the taller atrium. Once guests are delivered to their room, they’ll enjoy views into the atrium from their balconies. Barber talks about giving visitors views into multiple scales at once, and cut into the hotel corridors are glass-walled observation decks that look into the atrium—a rarity for hospitality companies that often want to squeeze guests into every possible nook and cranny. This, along with the orienting centrality of the atrium, is one way that Gaylord National Harbor seeks to make its multi-scaled spaces approachable and comprehensible. “Although it’s an extremely large building, it’s meant to be easy to understand,” Barber says. The hotel’s two elevator cores stand sentry on either side of the taller atrium. Once guests are delivered to their room, they’ll enjoy views into the atrium from their balconies. Barber talks about giving visitors views into multiple scales at once, and cut into the hotel corridors are glass-walled observation decks that look into the atrium—a rarity for hospitality companies that often want to squeeze guests into every possible nook and cranny. This, along with the orienting centrality of the atrium, is one way that Gaylord National Harbor seeks to make its multi-scaled spaces approachable and comprehensible. “Although it’s an extremely large building, it’s meant to be easy to understand,” Barber says.

Beyond the river

The bar-shaped convention center attached to the hotel offers 470,000 square feet of meeting space that is deeply customizable. Glass walls along the west façade give meeting attendees views to the river, and numerous skylights are generously cut into the ceiling.

Barber says the lopsided asymmetry created by attaching the convention center to one side of the otherwise symmetrical hotel gives the complex another way to approach and interact with the river. And once guests are there, they should have plenty to do. A dock with water-taxi service will connect the complex to downtown Washington and numerous bars, restaurants, retail shops, and hotels are coming together adjacent to the site. In the future, Barber hopes this point of access to the Potomac River will become just one node of waterfront development in a metropolitan area full of them.

“This is the tipping point of people realizing that we have a waterfront,” he says. |

For a building so concerned with precisely controlled and programmed interiors, the new Gaylord National Harbor Hotel and Convention center just outside the Washington, D.C., beltway expends a great amount of effort in projecting the visitor’s attention and experience outside the hotel to the Potomac River it borders. From back to front, the building changes its massing, scale, and landscaping to lead guests visually to the riverbank in terraced steps. The building’s vast glass and steel vaulted atrium is a telescopic projection that eyes the river as intently as a Colonial-era navigator in a clipper ship might have done.

For a building so concerned with precisely controlled and programmed interiors, the new Gaylord National Harbor Hotel and Convention center just outside the Washington, D.C., beltway expends a great amount of effort in projecting the visitor’s attention and experience outside the hotel to the Potomac River it borders. From back to front, the building changes its massing, scale, and landscaping to lead guests visually to the riverbank in terraced steps. The building’s vast glass and steel vaulted atrium is a telescopic projection that eyes the river as intently as a Colonial-era navigator in a clipper ship might have done. Two thousand hotel rooms wrap around both atriums, from the sides and the rear, making the $865 million, 2.5 million-square-foot Gaylord National Harbor the largest combined hotel and convention center on the East Coast. Below the steel and glass atriums, the hotel volumes are primarily constructed of precast concrete and rough-cut stone at it their base. The shoebox-shaped convention center connects to the complex on the south side of the 42-acre site and also faces the river to the west.

Two thousand hotel rooms wrap around both atriums, from the sides and the rear, making the $865 million, 2.5 million-square-foot Gaylord National Harbor the largest combined hotel and convention center on the East Coast. Below the steel and glass atriums, the hotel volumes are primarily constructed of precast concrete and rough-cut stone at it their base. The shoebox-shaped convention center connects to the complex on the south side of the 42-acre site and also faces the river to the west. This is a starkly literal approach to incorporating geography, history, and culture into a building’s parti, and it’s quite Gaylord’s style. At Gaylord Palms outside of Orlando, the hotel and convention center developer stepped outside of local geography to fuse together three different set pieces. There, guests can stroll through an Everglades swampscape, a tropical island Key West recreation, and a Colonial Spanish village styled after St. Augustine, Fla. At Gaylord Opryland, guests can ride and an indoor Delta flatboat through a tour of its atrium.

This is a starkly literal approach to incorporating geography, history, and culture into a building’s parti, and it’s quite Gaylord’s style. At Gaylord Palms outside of Orlando, the hotel and convention center developer stepped outside of local geography to fuse together three different set pieces. There, guests can stroll through an Everglades swampscape, a tropical island Key West recreation, and a Colonial Spanish village styled after St. Augustine, Fla. At Gaylord Opryland, guests can ride and an indoor Delta flatboat through a tour of its atrium. The terraced progression of the space under the atrium also leads visitors’ gazes and bodies to the river. Above the check-in lobby and reception area is another terrace, which sits under the taller of the two atriums and offers the widest views up, across, and out of the atrium. From here, the transition to the more intimate scale of the town square looks drastic. But, from the wide views of the upper and lower terraces to the colonial village, the scale of views and orientation is gradually reduced until the human-scaled town square comes into focus and visitors are led to the glass wall that looks out to the river. Once outside, guests are further enticed to the waterfront by following a stream that leaves the atrium and flows towards another fountain on the riverbank. This fountain is the centerpiece of terraced landscaping that also steps down towards the river, gradually modulating access to the Potomac.

The terraced progression of the space under the atrium also leads visitors’ gazes and bodies to the river. Above the check-in lobby and reception area is another terrace, which sits under the taller of the two atriums and offers the widest views up, across, and out of the atrium. From here, the transition to the more intimate scale of the town square looks drastic. But, from the wide views of the upper and lower terraces to the colonial village, the scale of views and orientation is gradually reduced until the human-scaled town square comes into focus and visitors are led to the glass wall that looks out to the river. Once outside, guests are further enticed to the waterfront by following a stream that leaves the atrium and flows towards another fountain on the riverbank. This fountain is the centerpiece of terraced landscaping that also steps down towards the river, gradually modulating access to the Potomac. The hotel’s two elevator cores stand sentry on either side of the taller atrium. Once guests are delivered to their room, they’ll enjoy views into the atrium from their balconies. Barber talks about giving visitors views into multiple scales at once, and cut into the hotel corridors are glass-walled observation decks that look into the atrium—a rarity for hospitality companies that often want to squeeze guests into every possible nook and cranny. This, along with the orienting centrality of the atrium, is one way that Gaylord National Harbor seeks to make its multi-scaled spaces approachable and comprehensible. “Although it’s an extremely large building, it’s meant to be easy to understand,” Barber says.

The hotel’s two elevator cores stand sentry on either side of the taller atrium. Once guests are delivered to their room, they’ll enjoy views into the atrium from their balconies. Barber talks about giving visitors views into multiple scales at once, and cut into the hotel corridors are glass-walled observation decks that look into the atrium—a rarity for hospitality companies that often want to squeeze guests into every possible nook and cranny. This, along with the orienting centrality of the atrium, is one way that Gaylord National Harbor seeks to make its multi-scaled spaces approachable and comprehensible. “Although it’s an extremely large building, it’s meant to be easy to understand,” Barber says.