| Next to a Real Oasis, the Water + Life Museums Offer a Refuge of Sustainable Design The natural history of the desert and the human-designed infrastructure to make it livable come together in a landmark project.

Summary: The Water + Life Museums, by Lehrer + Gangi Design + Build, are the first LEED® Platinum certified museums. Both institutions are designed using infrastructural forms and materials that call attention to the industrial effort required to maintain human settlements in the desert and the need to preserve resources. The museum design uses several solar shielding techniques, a massive PV panel array, and radiant floor heating and cooling.

The museum complex also snatched the title away from a much higher profile project: AIA Gold Medal recipient Renzo Piano’s California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco. Were it not for the largest earthworks project ever undertaken in the nation, the museum campus wouldn’t even exist. The two museums that make up the complex are in the Southern California desert, next to Diamond Valley Lake, a reservoir that came about after the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California dug 150 feet into bedrock to build two two-and-a-half mile long dams between two mountain ranges. The reservoir holds 260 billion gallons of water and took two years to fill. The Western Center for Archaeology and Paleontology exhibits rare items unearthed by this excavation, and the Center for Water Education was founded to tell the story of the desert water industry. The building’s formal language is tribute to the incredible effort required to bring water to desert cities—and as Lehrer says “the timeless idea of what it takes to run civilization.”

Lehrer speaks of being inspired by the utilitarian forms of water infrastructure along the Colorado River. “You viscerally get to see the day-to-day, minute-to-minute work of providing water,” he says.

Lehrer says that by adopting a design vocabulary that’s rarely used for aesthetic appreciation by the public, he’s making visitors aware of the nearly invisible water resources industry and then encouraging people to help preserve it. “To change people’s habits, it has to become part of their consciousness,” he says.

Lehrer says he never felt formally or aesthetically handcuffed by the project’s stiff (self-imposed) sustainability mandate. If anything, he says, these restrictions were “incredibly enriching,” because they gave him a framework for refining the design.

This kind of economical design rigor has gotten him recognized before. Lehrer’s firm (Lehrer Architects) won a 2008 Interiors AIA Honor Award for their renovation of their own office. For $125,000 (about $20 per square foot), they converted a dilapidated warehouse into a bright and spacious workplace. AIA Los Angeles gave the Water + Life Museums a 2008 Design Award as well. The museums (which opened a year and a half ago) were the product of a design-build partnership among Lehrer; Mark Gangi, AIA, of Gangi Architects; and his brother Frank Gangi, the project’s construction manager, all based in Los Angeles. Lehrer says the collaboration within Lehrer + Gangi Design + Build meant that the entire process was driven by sustainability and design, not bottom lines. “The fact that we were on the same side is why we ended up getting LEED Platinum for this,” he says.

Lehrer thinks that might be a nice goal. “In architecture, for me, it’s not an option,” he says. “The mission of architecture is—you solve your problems and you lift the soul. That’s the work.” |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› California Academy of Sciences Evolving Green

› Cultural Cornerstone Anchors Grand Rapids Revitalization

› National Law Enforcement Museum to Grace Nation’s Capital

› Sustainability, the Straw that Stirs Las Vegas’ Springs Preserve

Visit Lehrer Architects Web site

Visit Gangi Development’s Web site

Captions

1. Lehrer + Gangi Design + Build’s Water + Life Museums are the first LEED® Platinum certified museums. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

2. The architect wanted the long, narrow 70,000-square-foot museum complex to define the highway experience for visitors traveling past, Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

3. Each museum consists of five 46-foot tall brushed-steel towers that contain exhibit galleries. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

4. To combat solar heat gain from the desert climate, the towers in each museum are heavily insulated and completely opaque. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

5. To combat solar heat gain from the desert climate, the five towers in each museum are heavily insulated and completely opaque. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

6. The buildings’ simple rhythm of orthogonal forms stands in singular contrast with the flowing desert landscape. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

7. The PV array’s 30,000 panels generate almost half of the museum campus’s power. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

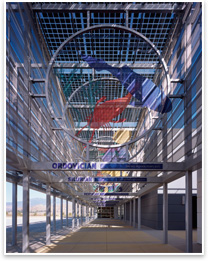

8. Between the towers are interstitial spaces walled by glass and partially covered by graphically decorated banners. Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

9. Between the towers are alternating glass-walled spaces partially covered by replaceable banners that Lehrer calls “theatrical scrims.” Photos © Benny Chan, Michael Lehrer, FAIA.

See what the Committee on the Environment is up to.

Do You Know SOLOSO?

The AIA’s resource knowledge base can connect you to “Desert Architects: Creating Livable and Sustainable Places” an audio/visual presentation from the AIA convention in which four voices of award-winning architecture driven by the constant pursuit for design quality present and discuss several recent projects.

See what else SOLOSO has to offer for your practice.

From the AIA Bookstore:

Building Type Basics: Museums, by Arthur Rosenblatt (John Wiley & Sons, 2000)

How do you . . .

How do you . . .