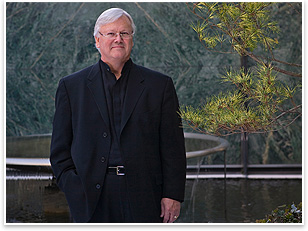

| Adrian Smith, FAIA, RIBA

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: Adrian Smith, FAIA, is a partner with Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, and was formerly a design partner in the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where he worked on some of the world’s most recognizable structures, such as the Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai; Rowes Wharf in Boston, and the Burj Dubai in the U.A.E., soon to be the world’s tallest structure. Projects under his design direction have won more than 90 awards for design excellence, including five international awards, eight national AIA awards, 22 AIA Chicago awards, and two Urban Land Institute Awards for Excellence. His work has been featured in major museums in the U.S., South America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. He is the author of two books on his architecture. Summary: Adrian Smith, FAIA, is a partner with Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, and was formerly a design partner in the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, where he worked on some of the world’s most recognizable structures, such as the Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai; Rowes Wharf in Boston, and the Burj Dubai in the U.A.E., soon to be the world’s tallest structure. Projects under his design direction have won more than 90 awards for design excellence, including five international awards, eight national AIA awards, 22 AIA Chicago awards, and two Urban Land Institute Awards for Excellence. His work has been featured in major museums in the U.S., South America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. He is the author of two books on his architecture.

Education

University of Illinois at Chicago, Bachelor of Architecture, 1969

Currently reading

I am currently reading the new James Patterson best seller, Sundays at Tiffany’s, and The Creative City by Charles Landry.

Favorite place to get away

My favorite place to get away is the south of France. However, I have not had time to get away since I started our new firm. Trips to Dubai and Abu Dhabi have been all consuming of my time lately. I have a country house in Lake County on 20 acres adjacent to a preserve that we can occasionally go to for weekend retreats.

How did you become interested in architecture?

I first became interested in architecture when I was in high school in California. I had always been interested in art and math as a child, and mechanical drawing introduced me to perspective and drawing buildings. I started researching architecture and read some books by Frank Lloyd Wright and started to travel around to see his buildings. I became enamored of his philosophy, his drawings, and his buildings. These had a strong influence on me for a while, and it was through this interest that I decided to study architecture as a profession. I also remember that as a child living in Chicago and a teenager coming back to Chicago, how struck by and in awe I was by the Chicago skyline. I think this was the point at which I became interested in skyscraper design.

Early professional background

I had an internship with Perkins + Will in Chicago in 1966. In 1967, I began my career at the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. While I was still a student at UIC, I worked on the John Hancock Tower—I was responsible for some parts of the basement and third-floor mechanical rooms of the tower—detailing some grills and laying out a tight mechanical room. In 1972, I moved to London to work on a project SOM had in England, the WD & HO Willis Hartcliffe projects in Bristol. I came back to Chicago after the project was completed and worked with Walter Netsch, Myron Goldsmith, Fazlur Kahn, and Bruce Graham. In the late ‘70s, I collaborated with Bruce Graham on the Banco de Occidente project and with Ricardo Legoretta and Luis Barragan on the Grupo Industrial Alfa Headquarters. It was through this relationship that I formed my philosophy of Contextualism and sensitivity to sustainability. I was elected a design partner at SOM in 1980.

How is your current work different from your career at SOM?

My current work and the projects we’re working on at AS+GG (we have 23 projects in the office right now) is very much an evolution of my earlier work at SOM. My work has always embraced Contextualism, the idea that a building should be a natural extension of its context and respond to the climate and culture of a region. Contextual architecture celebrates a region’s history by utilizing local materials and historically successful design concepts—often natural ventilation and light—but they interpret these forms and materials in a very modern way, so as to add to the vocabulary of a landscape. These projects are often extremely efficient and work with the climate of a local environment instead of against it.

My current work continues to explore these concepts, although now we’re looking beyond simply integrating passive energy systems to incorporating new technologies and building systems so that the architecture is modern from both an aesthetic and performance perspective. But it’s not an additive process; you have to look at each project holistically. You still need to start with a strong understanding of climate and environmental context, and then work to integrate both passive and active systems into the design to create a symbiotic relationship with the building’s environment.

Tall landmark structures such as the Burj Dubai and forthcoming Pearl River tower have a particular responsibility to be as sustainable as possible. How do the sometimes opposing technologies required for creating tall and sustainable buildings come together?

The technologies aren’t really opposing. Tall buildings are inherently sustainable because they can accommodate a larger number of people on a smaller land footprint. They also encourage sustainable transit. Elevators are one of the most sustainable modes of transit, and people who live in high-rises in dense areas walk and take public transportation much more than people who live outside of the city. But super-tall buildings can have other advantages over lower-rise structures in the quest to be sustainable. Because it is so large, the Burj Dubai has an innovative condensate collection system that captures enough water to fill 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools every year, water that will be used for irrigation purposes on site. Pearl River actually changes the behavior of wind at the building’s site and takes advantage of the power generated to power the building. Tall buildings have larger surface areas and direct access to sunlight, making it easier to take advantage of natural daylight and capture solar energy. The structural systems also require a certain depth, which increases the potential for geothermal energy. Wind energy is greater the higher one goes into the atmosphere and harvesting wind energy becomes more viable in taller buildings. The air temperature 100 stories up is also about 10 degrees Fahrenheit cooler, and we are finding ways to use this cooler air to help condition the building in warm climates.

What would be your dream project?

A mile-high, zero-energy vertical city.

Best practice tip for colleagues

Collaborate with other professionals, both within the profession of architecture as well as unrelated-field professionals. |