SUSTAINABILITY SUSTAINABILITYThe Duty to Beauty Summary: Sustainability always seems exempt from the crime of banal building. Why is this? I think it has something to do with mom and apple pie. Second-rate (and worse) pieces of architecture that claim the mantle of sustainability always have a “Get out of Jail Free” card safely tucked away. “It’s an awful design,” goes the logic, “but it’s sustainable, so we’ll let it pass.” There’s reluctance to slam something that’s trying to do good. Mom, apple pie, and sustainability—who dares to complain?

“An aesthetically inferior work of architecture,” says Wines, “no matter how environmentally correct in terms of green technology, cannot justify the investment, enhance a client’s public image, or qualify as sustainable design, simply because people will never want to keep a boring building around.” Great architecture and green architecture are one and the same—you cannot have one without the other. Attention to design has its Darwinian dimension: the higher a building’s architectural quality, the more likely we are to conserve, save, and recycle it.

By now, most of us can recite in our sleep the essential technical elements of green architecture: build with local materials, use recycled or recyclable materials, use diverse energy sources to lessen our dependence on fossil fuels, cut out anything emitting chemicals that deplete the ozone layer, take advantage of the latest environmental technology. As do many other leaders in green architecture, Wines has such a slide in his lecture. But he also has another slide containing a list that broadens and deepens architecture’s mission to be truly sustainable: include social and psychological sources of content, respond to the spirit of the age of information and ecology, absorb cultural diversity wherever you build (beyond Euro-centric traditions), transform green technology into an aesthetic language, integrate ideas drawn from the surrounding context, create a design language for the 21st century. These goals move us beyond merely specing the right green widget. Architects have a greater role to play.

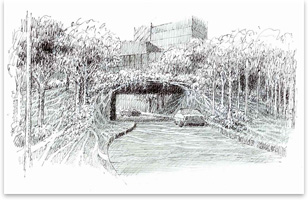

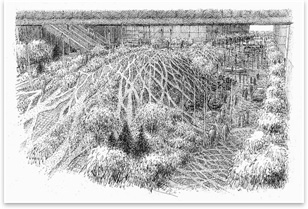

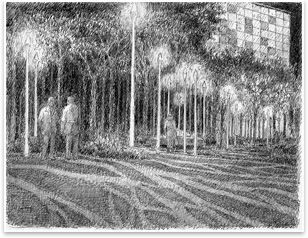

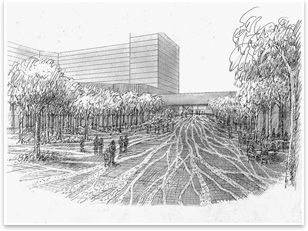

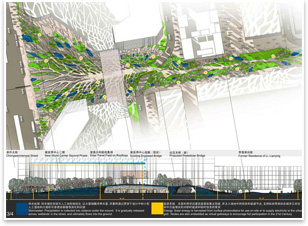

Esthetically, the design relates the shape of the site to expanding tree branches and river tributaries—images prevalent in Chinese art and iconography. Ribbons of concrete are framed by green swaths for planting groves of trees. Overlaid as part of the design are irregularly shaped enclosures defined by plantings, earth mounds, water catchments, seating areas, rain shelters, various paving textures, and buds of LED lights on tree-like lampposts.

|

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Michael J. Crosbie, PhD, AIA, writes extensively about architecture and design and is chairman of the University of Hartford’s Department of Architecture. He can be reached by e-mail .