| INTEGRATED PRACTICE Building Google Earth

The firm planned a few conventional celebratory activities—a lecture series, a second firm monograph—and one very unusual one: they decided to create digital models of about 40 of the firm’s buildings and submit them to Google Earth. Anyone can create Google SketchUp models of buildings or other artifacts of the built environment and place them in the Google 3D Warehouse, where they are available to be displayed on their actual sites in Google Earth by anyone who knows how to find the model files. But DMSAS decided to take the next step and formally submit their models to Google for incorporation into Google Earth itself, so that anyone in the world who happens to view, say, downtown Fort Worth would see detailed models of the buildings DMSAS designed there. (Google Earth is freely available to anyone and can be downloaded from their Web site.) The project was the brainchild of firm principal Thomas H. Greene, AIA. He and the firm had long been in the habit of using Google Earth for projects and prospective projects. “I would look at a place where we might have a prospective project,” he says. “It might be a riverfront site in Arkansas, for example. I would study the town, the topography, and get a feel for the place.” These “virtual site visits” had become so routine that Greene frequently used Google Earth “to scope out vacation plans.” While studying downtown Minneapolis on Google Earth—a city that is particularly well-modeled—it occurred to Greene that there was no reason why architects couldn’t model and submit their own buildings, and many reasons why they should. Reasons why you should The Google Earth interface allows submitters to create a “collection,” thumbnail images that can be easily scrolled and that allow users to fly around the Earth from one building in the collection to another: a digital portfolio, with each building displayed in its actual geographic context. “People who look at D.C. in Google Earth will see mostly monuments,” says Greene. “Until more buildings are modeled, our buildings will stand out among those few.” The rest of the city—or any other city—will consist of gray massing models, the default placeholders that Google Earth uses to represent 3D buildings.

Julian Goldman, the intern architect who developed the firm’s first Google Earth model, adds: “When people search for information on the Internet, instant gratification comes into play. If you can find vast amounts of information about a firm on the Internet, it feels more present or accessible. When I’m looking for a store or service, if it doesn’t have an Internet presence, then as far as I’m concerned, it doesn’t exist. The speed with which detailed information about our firm can be accessed online is enhanced by being in Google Earth.” Some practical tips It takes about three to four months for Google to place models into Google Earth once they are submitted. In the meantime, authors can place models in the Google 3D Warehouse, but people interested in viewing them have to know that the models are there and “retrieve” them to display them in Google Earth. Models submitted to Google Earth become the property of Google. Anyone can download a 3D SketchUp model and modify it or use it for another purpose. This may be a matter of some concern to architects, but DMSAS believes that the benefits outweigh the risks. The SketchUp models themselves are so “sketchy” as to be of little value for design by anyone who may be intent on stealing a design concept. They gain little more information in the process than they could gain by visiting the building and photographing it, or looking at photographs in a book or magazine. DMSAS regards the information in their Google Earth models as being closer in nature and type to publishing than to digital design information. And, after all, anyone can create SketchUp models of any building and submit it to Google Earth. Architects who model and submit their own buildings get to control the message.

As DMSAS looks forward to its next 30 years, submitting models of their buildings to Google Earth will become a routine part of their marketing and public relations efforts. They also see additional benefits. “We continue to build where we’ve built before,” says Greene. “Putting projects into the urban context is a big part of what we do here. We design not just buildings, but the environment around them. In the past, we’ve had the opportunity to reuse physical models of city blocks developed for previous projects. Getting our buildings into the massing of a whole urban area in Google Earth is appropriate to our way of thinking.” Copyright 2008 Michael Tardif |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› AIA Teams Up with Google to Launch New Architecture Layers in Google Earth

› BIM: Reaching Forward, Reaching Back

› BIM Storm Hits LA

Michael Tardif, Assoc. AIA, CSI, Hon. SDA is a design technology analyst and consultant in Bethesda, MD.

Photos:

Image 1: A typical page in the Google 3D Warehouse shows an image of the selected building (in this case, Sundance East in Fort Worth by DMSAS), the text description that accompanies it, a hyperlink to the firm’s Web site, and the Google collections to which that building belongs, including the firm’s own Google 3D Warehouse portfolio.

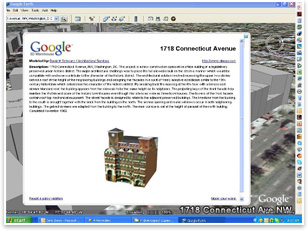

Image 2: A 3D model in Google Earth of 1718 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C., by David M. Schwarz Architectural Services, Inc.

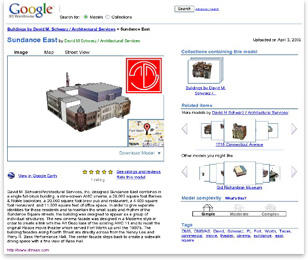

Image 3: The icon above the model in Google Earth links to a text description. In the upper left is a hyperlink to the firm’s collection of models in the Google 3D Warehouse, in the upper right a hyperlink to the firm’s Web site.

The statements expressed in this article reflect the author’s own views and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the American Institute of Architects. Publication of this article should not be deemed or construed to constitute AIA approval, sponsorship, or endorsement of any method, product, service, enterprise, or organization.

Summary:

Summary: