Modern Buildings: A More Nuanced Notion of Worth

Many communities within the U.S., however, have proved unable to move beyond a rather fixed definition of history. For a general audience to whom Colonial and even Colonial Revival styles seem historic and beautiful, there is little public support for the preservation of structures that challenge established community notions of beauty and history. This has very real implications for the integrity of the built fabric of cities. As an architectural style, Modern buildings tend to confront most directly the less-nuanced appreciations of historical value. Because these buildings largely rejected the role and place of more classical building elements, it is difficult for some communities to see them as being historic, because they do not visually reference the styles inherent in the communities’ idea of history. The result is that many cities and towns throughout the U.S. are ill-equipped to include Modern structures in their understanding of the historic built environment.

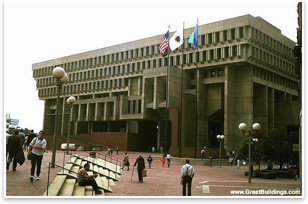

In short, while the historic preservation community has been able to widen what it considers historical, communities at large have generally not been able to do this. The fundamental question then becomes why: Why have communities generally set their conception of the types of structures that may be considered historical? Example: Boston City Hall In general, the conflation of history and beauty has tended to prevent an evolving sense of the kinds of buildings that may be considered historic; that is, seen as containing historical value to the community. Many communities retain ideas about what constitute historical structures that reflect older trends in historic preservation. These ideas, when confronted with newer architecture, do not provide an adequate framework through which to integrate the contributions made by these newer buildings to the larger historical narrative reflected in the built fabric. The implication is that some communities, in conflating history with beauty, have fixed, mutually reinforcing definitions of history and beauty. Structures that present a different aesthetic and a more general, evolving historical sense are not seen to be historical. Consequently, these structures are not afforded the protection offered by historic preservation. Not all Modernist structures are worth saving. They do deserve consideration, nonetheless, because they form a valid documentary source for specific moments in time, just as other, more accessible structures are. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

1.

Photo © Howard Davis.

2. Photo by davebluedevil

This article is a synopsis of Seth Tinkham’s master's thesis just completed at the University of Heidelberg on the preservation of Modern, particularly Brutalist, buildings, which features Boston City Hall as a case study.