Preserving Modern Architecture: What, Why, Where, and How?

The sheer quantity of resources, coupled with the relative youth of buildings often not yet recognized as historic, present unprecedented challenges. This article examines some of the existing mechanisms used by preservationists to identify and assess the building stock that makes up Modern architecture.

Conferring official recognition is usually based on two elements: significance and integrity. A building’s significance and its overall integrity are the basis for conveying official recognition and designation whether locally, regionally, nationally, or internationally. That recognition may result in even more positive and active forms of protection. Assessing significance—that is, identifying those elements of a building or site that make it more important than others and thus worthy of protection—relies on a historic narrative that places the property in an architectural, historical, social, and cultural context. In essence, a case must be made that the building or site is worthy of preservation. Historically, the significance of a building or site is established by its uniqueness: that it is rare, special, or the last or best of its kind. This value system, which establishes peerlessness—to some extent merely the result of survival—as an important signpost of significance thus allows one-of-a-kind status to become a selection criterion almost by default. A value system based on singularity remains applicable to the iconic buildings of Modern architecture, but the preservation field has expanded its mandate to include broader criteria and assessments for significance beyond age and rarity. Additionally, the field has incorporated groups of buildings, different building types and sites, and cultural landscapes—whether geographically contiguous, such as neighborhoods, or in some other thematically related form. This thematic relationship may involve individual structures that are grouped together as a collection because of their social, cultural, historic, architectural, or technical significance. Alternatively, each structure may not be of iconic significance individually but may be noteworthy collectively. Where the significance is in the collectivity, the entire group can be designated following standard preservation processes. Where each and every one of the structures is important, then a process to select the most important ones within the theme can, if necessary, be established.

When this general process for determining significance and assessing integrity is applied to the preservation of Modern architecture, and when it is applied to other kinds of architecture, some major differences occur. Compared with older, more traditional buildings and sites, three factors make the determination of significance for Modern architecture richer, but also more complex:

And this complexity also affects the assessment of integrity. In the assessment of more traditional buildings, the amount of original fabric remaining has been emphasized either related to its original construction or its period of significance. Integrity has concerned itself largely with material authenticity. For the assessment of more contemporary structures, the assessment criteria have to be expanded to include a broader definition of authenticity and the concept of design intent. It is not just how much remains of the original material that is important, but how much of the original design is recognizable and visually cohesive as well. Determining significance

Reflecting the eligibility reasoning in many national and international guidelines, the U.S. criteria for evaluating historic properties for listing districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects on the National Register note that they should represent a quality of significance in U.S. history, architecture, archeology, engineering, and culture that possesses integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association that includes association with significant historical events or with the lives of significant persons. Although Modern buildings will likely meet one or more of these general criteria, these traditional definitions of significance have been expanded by, for instance, DOCOMOMO and others, with such considerations as innovation—whether in aesthetic, social, or technical terms—as a way to represent better the value of Modern architecture. Thus, the assessment of significance and eligibility takes into consideration the prevalence of technical and social innovations embraced by architects of the period. The quantity of buildings also creates the very practical dilemma of how to study, analyze, and determine what to save. Even as research and academic scholarship grows, not enough of that scholarship has found its way into easily accessible sources or the preservation literature to aid in establishing the historic context and significance criteria to be applied to the first step of the standard preservation process. For that purpose, one of the most frequently used tools in tackling the recent building stock is the theme or thematic study—essentially a comparative analysis of data used to arrive at a hierarchy of significance and a basis for decision making.

(Ed note: the third topic of Identification and Documentation: Thematic Surveys by Topic and Theme is covered extensively in Chapter 5 of Preservation of Modern Architecture.) Conclusion Whereas significance and the justification for preservation can be argued to a large degree on the basis of existing criteria or the interpretation thereof, the relationship among integrity, design intent, and authenticity as it relates to Modern architecture is as yet largely unexplored and remains to a large degree subjective. Clearly, the balance among these three fundamental elements is one that needs to be considered carefully and extensively in the future. Copyright 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

Preservation

of Modern Architecture, by Theodore H.M. Prudon will be published this

spring by Wiley & Sons. This excerpt is reprinted with permission.

Preservation

of Modern Architecture, by Theodore H.M. Prudon will be published this

spring by Wiley & Sons. This excerpt is reprinted with permission.

Special thanks to Wiley Architecture and Design Acquisitions Editor John Czarnecki, Assoc. AIA, for his help in obtaining this material.

Photos:

All images courtesy John Wiley & Sons.

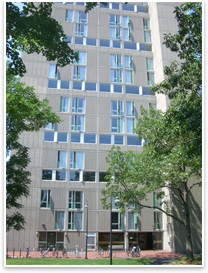

Images 1 &2: The Francis Greenwood Peabody Terrace in Cambridge, Mass., by José Luis Sert, commissioned 1962, completed 1964. Bruner/Cott & Associates was the architect for the 1993-95 renovation. Extensive spalling of the poured in place concrete resulted primarily from corrosion of rebars and the insufficient concrete cover because the original design aimed at economizing on materials. Unlike earlier patching, the 1993 renovations carefully analyzed the existing concrete to find the best visual match possible. By shaping the patches more clearly, the haphazard look characteristic of the earlier repairs was avoided. Photos copyright Theodore Prudon.

Image 3: The original Broadway elevation of the Julliard School of Music, by Pietro Belluschi in association with Eduardo Catalano, completed in 1969, which is currently undergoing substantial renovation and rebuilding (pictured in 1998). In the background, note the bridge over 65th Street connecting the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts north plaza to Julliard. Photo copyright Theodore Prudon.

Image 4: The travertine cladding of the Julliard School (pictured 2007) has been removed in preparation for the construction of the new cantilevered addition, and the bridge over 65th Street has been removed. Photo copyright Flora Chou.

Image 5: General exterior view of the Lingotto Factory assembly plant, Turin, Italy, by Giacomo Matté Trucco, commissioned in 1914, which underwent two distinctive changes in the renovation begun in 1989 by the Renzo Piano Workshop. The original steel framed multi-paned windows were replaced with a similar but not identically gridded set of windows. On the exterior, a roll-down fabric shade was added. Photo copyright Theodore Prudon.