Saving Our Future by Building on Our Past

Sustainability and green concerns form part and parcel of the soul of historic preservation. As preservation architect James Kienle, FAIA, pointed out in his article “That Old Building May Be the Greenest on the Block” in the February 8 AIArchitect: “Architects must understand that new green buildings are but one of the factors along with historic and natural resource integration that provides the full answer to a sustainable built environment.” In this issue, Pfeiffer Architects explains their mission to renovate Washington State University’s Compton Union Building and preserve its character while achieving LEED® certification. Going back further in time, Henry Wright’s Ramirez Solar House, under the watchful eye of the National Park Service, shows us that sustainability and green-architecture roots extend back to back to the earliest days of the Modern Movement.

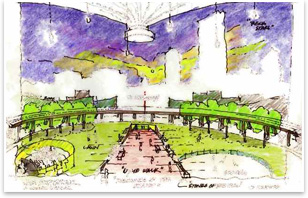

Despite the diversity, this issue comes nowhere close to being the be-all or end-all word on saving Modern buildings. It merely offers a snapshot in time. Integrated practice, the third Institute strategic initiative, typically refers to a process that emphasizes early and ongoing contributions of knowledge and experience from all team members as well as use of building information modeling. It is a priority for the restoration of the AIA headquarters building and seems tailor-made for preservation projects. Robert Pfaffmann, AIA, invites brainstorming from everyone to reshape Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena. As a tool, we see building information modeling as the next frontier for restoration. If you are using it, let us know, and we’ll share your process with our readers in a future issue.

These people work hard, care long, and contribute much. We dedicate this edition to them. Thanks to all who contributed to the issue; we received more great material than we could publish. —The Editors. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

1. The 1972 AIA headquarters building, Washington, D.C., designed by the Architects Collaborative, is about to undergo major restoration work. Photo from the AIA Archives.

2. A fish-eye view of the 1954 Ramirez Solar House, designed by Henry Wright Jr. and currently under the watchful eye of the National Park Service. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

3. The 1956 TWA Corporate Headquarters Building in Kansas City, Mo. by Raymond Bales and Morris Schechter, is the first building to be restored—by el dorado inc.—using State of Missouri and Federal Historic Tax Credits. Photo © Timothy Hursley.

4. A sketch by Robert Pfaffmann, AIA, for the restoration of Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena, designed in the 1950s by architects James A. Mitchell and Dahlen K. Ritchey. Sketch courtesy of the architect.