Rehabilitation

of Henry Wright’s Ramirez Solar House

by Thomas Solon, AIA

National Parks Service

Summary: The

Ramirez Solar House sits off Raymondskill Falls Road just south of

the town of Milford, Pa., in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation

Area, a unit of the National Park Service. Designed in 1944 by architect

Henry Wright Jr., FAIA; the Ramirez Solar House is believed to be

one of the earliest examples of a passive solar home in existence.

Wright was the son of Henry Wright, town planner, who, in partnership

with Clarence Stein, designed many of the early garden cities, including

Radburn, N.J., and Sunnyside, Queens, N.Y. Henry Wright Jr. was famous

in his own right, notably as editor of Architectural

Forum magazine,

educator, and author of dozens of articles on architecture and engineering,

not to mention as an early practitioner of passive solar research

and design. Summary: The

Ramirez Solar House sits off Raymondskill Falls Road just south of

the town of Milford, Pa., in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation

Area, a unit of the National Park Service. Designed in 1944 by architect

Henry Wright Jr., FAIA; the Ramirez Solar House is believed to be

one of the earliest examples of a passive solar home in existence.

Wright was the son of Henry Wright, town planner, who, in partnership

with Clarence Stein, designed many of the early garden cities, including

Radburn, N.J., and Sunnyside, Queens, N.Y. Henry Wright Jr. was famous

in his own right, notably as editor of Architectural

Forum magazine,

educator, and author of dozens of articles on architecture and engineering,

not to mention as an early practitioner of passive solar research

and design.

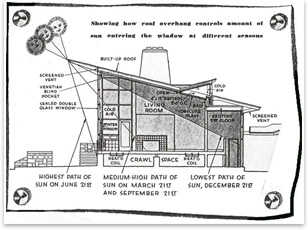

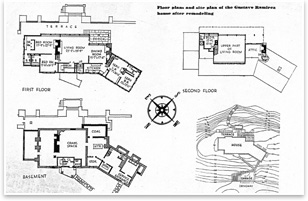

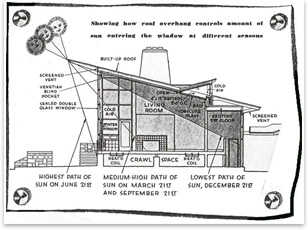

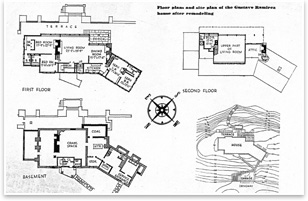

Interest in passive solar heating emerged in Europe in the years

following the First World War where, according to renowned architect

Marcel Breuer, a major goal of the German housing movement was to

save fuel with solar energy. In particular, Wright’s Ramirez

Solar House has a large 18-foot-tall window wall on its southeast

side, permitting the sun’s energy to warm the living room in

winter, and a roof overhang to shade the window wall from the summer’s

mid-day heat. The Solar House is a remodeling of a 1910 summer home

that was already on the site, so it represents not just early passive

solar design but also sustainable renovation. By necessity, wartime

modifications reused much of the original building material. Interest in passive solar heating emerged in Europe in the years

following the First World War where, according to renowned architect

Marcel Breuer, a major goal of the German housing movement was to

save fuel with solar energy. In particular, Wright’s Ramirez

Solar House has a large 18-foot-tall window wall on its southeast

side, permitting the sun’s energy to warm the living room in

winter, and a roof overhang to shade the window wall from the summer’s

mid-day heat. The Solar House is a remodeling of a 1910 summer home

that was already on the site, so it represents not just early passive

solar design but also sustainable renovation. By necessity, wartime

modifications reused much of the original building material.

Wright enhanced the effectiveness of his solar heating design at

the Ramirez House by introducing built-in technological improvements.

The use of such large glass areas in an intemperate climate though,

posed a threat to comfort. A Venetian-blind pocket above the window

wall together with curtain tracks supported blinds and curtains.

These window treatments protected the occupants from glare and provided

some control over excessive solar gain and heat loss. Wright enhanced the effectiveness of his solar heating design at

the Ramirez House by introducing built-in technological improvements.

The use of such large glass areas in an intemperate climate though,

posed a threat to comfort. A Venetian-blind pocket above the window

wall together with curtain tracks supported blinds and curtains.

These window treatments protected the occupants from glare and provided

some control over excessive solar gain and heat loss.

To more effectively reduce heat loss, Wright used insulating glass.

This was a relatively new product at the time that was manufactured

by creating a metal-to-glass hermetically sealed air space between

two sheets of glass. Introduced by Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass in 1935,

Thermopane glass reduced heat loss by 50 percent. It also tolerated

much higher inside relative humidity by overcoming the problem of

condensation that usually occurs with a single sheet of glass. To

warm the downdrafts of cold air falling against his window wall,

Wright installed removable “winter windows” eight inches

behind the bottom five feet. These inner windows channel downdrafts

of falling air to concealed radiators below. Before reaching the

floor, the warmed air is deflected into the room. In addition, he

installed under-floor radiators, crawlspace heating coils, clerestory

radiators, etc.—all using the original steam heating system

for economy. (These details were thoroughly documented by Architectural

Forum and House Beautiful magazine in 1944 and 1945.) To more effectively reduce heat loss, Wright used insulating glass.

This was a relatively new product at the time that was manufactured

by creating a metal-to-glass hermetically sealed air space between

two sheets of glass. Introduced by Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass in 1935,

Thermopane glass reduced heat loss by 50 percent. It also tolerated

much higher inside relative humidity by overcoming the problem of

condensation that usually occurs with a single sheet of glass. To

warm the downdrafts of cold air falling against his window wall,

Wright installed removable “winter windows” eight inches

behind the bottom five feet. These inner windows channel downdrafts

of falling air to concealed radiators below. Before reaching the

floor, the warmed air is deflected into the room. In addition, he

installed under-floor radiators, crawlspace heating coils, clerestory

radiators, etc.—all using the original steam heating system

for economy. (These details were thoroughly documented by Architectural

Forum and House Beautiful magazine in 1944 and 1945.)

The Wright way The Wright way

Henry Wright recognized that insolation is a mixed blessing—that

winter’s advantages are equaled if not exceeded by summer’s

disadvantages. He called, then, for the use of correct orientation

and selective shading devices to achieve year round comfort. His

aim was always comfort and economy, not 100 percent solar heating. “In

the process, the whole design of the house is modified,” Wright

said of solar heating. His interest in solar heating design opened

the door to “variable” elevations such that “The

house began to look like a ‘glass house’ only if it were

seen from one or two sides at the most.” This is an apology,

of sorts, to the average reader of Tomorrow’s House who had

not yet accepted Modern architecture or been weaned from traditional

styles. So, although Wright confessed to being a “convinced

Modernist,” he was hesitant to “drape an old fashioned

plan in a cubistic exterior.” Yet he denounced “the fakery

of bygone handicraft techniques.”

Instead he promoted the honest use of forms, materials, and technologies

that, when combined, formed a unified response to all that nature

had to offer. “From here on in, anyone who plans a house without

giving serious consideration to the operation of the solar house

principle is missing a wonderful chance to get a better house, a

more interesting house, and a house that is cheaper to run,” predicted

the authors of Tomorrow’s House. In light of this generation’s

focus on sustainable design and holistic resource management, the

relevance of Wright’s work is as clear as the noonday sun.

What next? What next?

The house has been unoccupied for more than 20 years. The probable

use for this historic property is foretold by a proposal to create

a sustainable design center. Frederick Schwartz, FAIA, has been

working with the Park Service to adopt and use the building. Schwartz

is an ardent advocate of green building, past winner of the prestigious

Rome Prize for Architecture, activist, and humanist whose career

has been dedicated to some of America's most visible public projects.

His visionary thought for the THINK team for the World Trade Center

site and his globally acclaimed new South Street Ferry Terminal

have established Frederic Schwartz Architects as among the most

creative architects working in New York City today. He is forming

a nonprofit for the express purpose of preserving this early example

of a Modern building and has offered to assist with preparing the

construction documents for the rehabilitation of the structure.

|