| SUSTAINABILITY Defusing Boomer Building Time Bombs

Throw-away consumerism was the rage, the American dream that we are now waking from, with a terrible ecological hangover. All around us, Boomer Buildings are crumbling. Many of them are on college campuses, where the pressure to build expediently during the post-war GI-Bill years was the greatest.

The sorry state of most Boomer Buildings today comes just at the point when sustainable design and construction have captured the architectural spotlight. Where in another age Boomer Buildings would be torn down, today architects are finding intelligent and sustainable ways to give them new life. As James Kienle, FAIA, noted in a recent AIArchitect article, re-using old buildings is one of the most sustainable things you can do as an architect. Rehabilitating the Boomers

These examples show that there are lots of ways to bring a Boomer Building back from the brink. Institutions, especially colleges, are willing to invest in a facility when the architect can demonstrate that there are more good years possible in a building’s lifespan without resorting to wholesale demolition and starting from scratch. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

recent related

› Sustainability Is in the Details

Michael J. Crosbie, PhD, AIA, writes extensively about architecture and design and is chair of the University of Hartford’s Department of Architecture. He is the editor of the book Boomer Buildings: Mid-Century Architecture Reborn, (Images Publishing, 2005), which profiles the sustainable work of Mitchell Giurgola Architects. He can be reached at crosbie@hartford.edu.

Captions

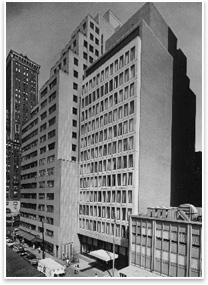

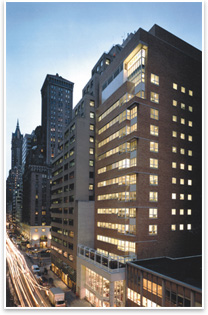

1. and 2. Before and After: The 1964 Lighthouse in midtown Manhattan

was stripped of its 14-stories of skin to allow a new, high-performance

envelope that also opened the building up to greater natural light

and allowed the headquarters to become a glowing “beacon.”

3. and 4. Before and After: On the campus of Queens College in New York, Mitchell Giurgola used the same technique of replacing the façade to turn a 1950s energy hog into a contemporary-use, high-performance building.

The “Before” photos are © Jeff Goldberg/ESTO. The “After” photos are courtesy of Mitchell Giurgola.

Summary:

Summary: Not easy to love . . .

Not easy to love . . .  On the campus of Queens College in New York, the same architects

dealt with a 1950s-era classroom building, an energy hog that contributed

little to the campus’s overall architectural flavor. Brick

walls were spalling, the fin-tube radiator heating system was substandard,

glass curtain walls were un-insulated, and there was neither access

for persons with disabilities nor community gathering space in this

important campus building. Stripping the building back to its concrete

column-and-slab frame allowed a new high-performance envelope to

be constructed that would also better relate to the existing campus

architecture. There was also an opportunity to transform two dilapidated

internal courtyards into verdant landscapes (designed by Thomas Balsley

and Associates) that use low-maintenance plant materials, have become

a haven for wildlife, and offer soft, green views from the building’s

interiors.

On the campus of Queens College in New York, the same architects

dealt with a 1950s-era classroom building, an energy hog that contributed

little to the campus’s overall architectural flavor. Brick

walls were spalling, the fin-tube radiator heating system was substandard,

glass curtain walls were un-insulated, and there was neither access

for persons with disabilities nor community gathering space in this

important campus building. Stripping the building back to its concrete

column-and-slab frame allowed a new high-performance envelope to

be constructed that would also better relate to the existing campus

architecture. There was also an opportunity to transform two dilapidated

internal courtyards into verdant landscapes (designed by Thomas Balsley

and Associates) that use low-maintenance plant materials, have become

a haven for wildlife, and offer soft, green views from the building’s

interiors. On the campus of Keene State College in New Hampshire, Mitchell

Giurgola saved a lab building that was woefully inadequate for contemporary

science instruction (along with a sub-par HVAC system, the building

lacked a centralized pure water system). The architects retrofitted

the existing envelope (which had single-pane glass and no insulation)

while designing a new wing that would permit the installation of

contemporary fume hoods and exhaust systems. In this case, the sins

of the Boomer Building were offset with new construction containing

generous chase space.

On the campus of Keene State College in New Hampshire, Mitchell

Giurgola saved a lab building that was woefully inadequate for contemporary

science instruction (along with a sub-par HVAC system, the building

lacked a centralized pure water system). The architects retrofitted

the existing envelope (which had single-pane glass and no insulation)

while designing a new wing that would permit the installation of

contemporary fume hoods and exhaust systems. In this case, the sins

of the Boomer Building were offset with new construction containing

generous chase space.