Modernism’s

Siren Song, Restored

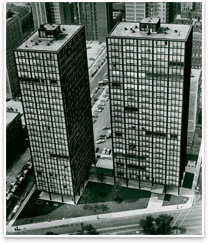

How do you . . . renovate a historic residential Modernist masterpiece? Pity poor Mies van der Rohe. When he and his throng of mid-20th century European expatriates washed up on American shores, their goal was to create a new Modernist language beyond style and trend, timeless in its perfection—an architecture of eternal ideas and ideals.

But what was once hoped to be timeless has aged, and iconography guarantees no shield against the passage of time. So when Krueck & Sexton Architects of Chicago were given the opportunity to renovate the two buildings, their goals were to protect Mies’ timeless vision and to transform its cultural vitality into a bulwark against the creeping comodification of architecture. “By taking good care of it, we’re ensuring that we’re going to pass this fantastic artifact on to the next generation to take care of,” says Krueck & Sexton’s Rico Cedro, AIA. “By being good stewards of the building as a cultural artifact, we’re also being good stewards of it as an environmental artifact.”

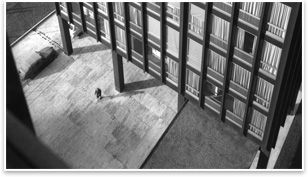

Cedro’s firm principals Mark Sexton, FAIA, and Ronald Krueck, FAIA, both attended the Illinois Institute of Technology where Mies taught from 1938 to 1958, and the firm had previously renovated the college’s architecture school, S.R. Crown Hall, which Mies designed, in addition to other Mies buildings in Chicago. Krueck & Sexton were hired by the buildings’ residents to fix insensitive renovations that have distorted the original lighting scheme and significantly deteriorated the travertine plaza to the point where water has infiltrated the parking garage below ground. The renovation will replace the aged travertine stones with more historically accurate matches, restore the original translucent glass in the lobbies, and repaint the structure in its signature Mies black.

“We could see every erasure that was made on the drawings,” says Cedro. “We could see where they struggled with certain details and others that seemed to be quite effortless.”

Cedro says such dogmatic dimensions and proportions of 860–880 were an unforgiving and exacting palate for renovation. “What was given to us in terms of dimensions we really had to stick to,” he says. “Because it’s a minimal structure, there’s not a lot of space to do things.” As a result of these renovations, Cedro says his firm learned more than they might have expected about the day-to-day operations and performance of the building. They encountered ventilation and building envelope problems that can’t be addressed with the current round of more superficial renovations, but Cedro says knowledge of sustainability practices helped him to understand how all the buildings’ functions and systems are related. Preservation without isolation Especially with residential projects, the architects restoring 860-880 have to preserve without isolating—to preserve in a way that allows the building to be an active partner in the dynamic social patterns that come with a structure that is inhabited 24 hours a day. The building “acts as a player upon them; they act as a player upon it,” says Cedro. “When you really spend a lot of time up close on a great work of art, it’s like spending three or four years restoring a painting. You really get to know all of it very intimately in all of its glories and all of its flaws too, and I think the flaws reveal part of the story of the building.” |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

thoughts and theory

big buildings

smaller scale

special issues

recent related

› Crown Hall Gets 50th Birthday Present

› Their Vision, Their Words, Our World

› Largest Modernism Exhibit Ever in U.S. Opens in DC’s Corcoran Gallery

Visit the Krueck & Sexton Architects Web site.

Read former New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp’s appraisal of Mies’ work in an Art Institute of Chicago exhibit from 1993—“Chicago Architecture and Design: 1923–1993.”

Credits:

1. and 2. Photos © Hedrich Blessing.

Photos 3, 4, 5, and 6. courtesy of the architect.

The fix

The fix

Dogma in the dimensions

Dogma in the dimensions