The

Pittsburgh Civic Arena: Memory and Renewal

by Rob Pfaffmann, AIA

Pfaffmann and Associates

Summary: This

article contains excerpts from an abstract prepared for the 2008

DOCOMOMO conference, “The Challenge of Change,” adapted

for this special edition of AIArchitect to explore what we have truly

learned from our past. It challenges the current belief that Modern

planning and design interventions are obsolete through a proposal

to reuse the Pittsburgh Civic Arena as an anchor for a new urban

plan that interweaves the multiple historic layers with Modern planning

themes. Summary: This

article contains excerpts from an abstract prepared for the 2008

DOCOMOMO conference, “The Challenge of Change,” adapted

for this special edition of AIArchitect to explore what we have truly

learned from our past. It challenges the current belief that Modern

planning and design interventions are obsolete through a proposal

to reuse the Pittsburgh Civic Arena as an anchor for a new urban

plan that interweaves the multiple historic layers with Modern planning

themes.

Urban renewal in Pittsburgh: success and failure Urban renewal in Pittsburgh: success and failure

The history of urban renewal in Pittsburgh is a story of success

and failure. Pittsburgh’s environmental reform movement is

most often cited, but less known are the sometimes innovative but

often failed efforts to redesign large areas of the city following

Modern design principles. Much of the legal basis for urban renewal

laws (eminent domain) in America was created in Pittsburgh during

the 1940s and ’50s.

A debate is now taking place in planning and architecture professions

in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. Pittsburgh,

the city experiencing the second greatest population loss outside

of New Orleans, also is challenged with the reconstruction of large

areas of the urban fabric devastated by urban renewal and economic

decline. Whether it is Pittsburgh’s Point State Park/Gateway

Center, East Liberty, or the Civic Arena/Lower Hill, each project

is a product of its time and prevailing view about urban design, architecture,

and economic renewal. The nature and extent of civic discourse and

examination of the failure to fully execute proposed plans is an

important component of these questions.

The profession/policies of American historic preservation have identified

the need to stand back from current popular views of a design or

style (the “50-year rule”). At the turn of the 19th century,

many believed that the “excesses” of the Victorian era

were not worth saving. That attitude translated into wholesale demolitions

of important fabric of our cities. Until Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses

clashed in the 1960s, many only saw these issues as ones of style,

not as a foundation for healthy city development. Pittsburgh, because

of its environmental and economic troubles, became a place where

Modern design principles were used extensively in the urban renewal

process. The profession/policies of American historic preservation have identified

the need to stand back from current popular views of a design or

style (the “50-year rule”). At the turn of the 19th century,

many believed that the “excesses” of the Victorian era

were not worth saving. That attitude translated into wholesale demolitions

of important fabric of our cities. Until Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses

clashed in the 1960s, many only saw these issues as ones of style,

not as a foundation for healthy city development. Pittsburgh, because

of its environmental and economic troubles, became a place where

Modern design principles were used extensively in the urban renewal

process.

What does it mean to “undo the past”?

Today, across Pittsburgh, major projects that propose to “undo

the damage of urban renewal” are well under way. As Pittsburgh’s

political leadership undertakes this effort, current urban design

and planning trends (New Urbanism, Contextualism, etc.) are assumed

to be preferable to the past Modern schools of thought regarding

planning and design.

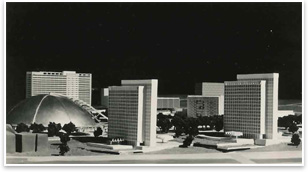

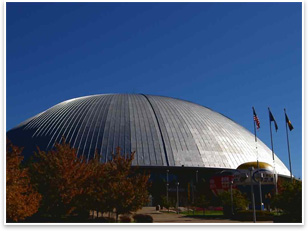

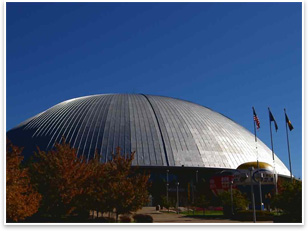

Pittsburgh’s Hill District, which is one of the nation’s

most important historic African-American communities, was extensively

destroyed for the Civic Arena, a project led by Edgar Kaufmann (Fallingwater’s

owner) and designed by architects James A. Mitchell and Dahlen K.

Ritchey. We must explore what we have truly learned from our past

and challenge the current belief that Modern planning and design

interventions are obsolete through a proposal to reuse the Civic

Arena as an anchor for a new urban plan that interweaves the multiple

historic layers with Modern planning themes.

Taking a cue from Jacobs: “Cultural or civic centers, can

probably in a few cases employ ground replanning tactics to reweave

them back into the city fabric. The most prominent cases are centers

located on the edges of downtowns . . . One side of Pittsburgh’s

new civic center, at least, might be rewoven into the downtown, from

which it is now buffered,” she wrote in The

Death & Life

of Great American Cities in 1962. Taking a cue from Jacobs: “Cultural or civic centers, can

probably in a few cases employ ground replanning tactics to reweave

them back into the city fabric. The most prominent cases are centers

located on the edges of downtowns . . . One side of Pittsburgh’s

new civic center, at least, might be rewoven into the downtown, from

which it is now buffered,” she wrote in The

Death & Life

of Great American Cities in 1962.

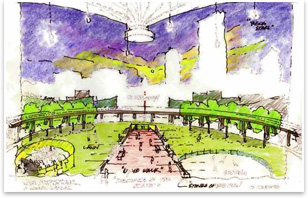

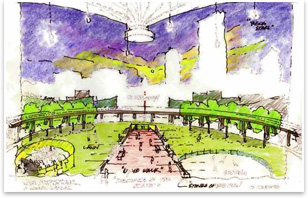

Brainstorming: ideas to build upon

- Reinvent Mellon Arena as an innovative community anchor.

- Take a holistic approach to the entire Hill: a supermarket,

more affordable housing over a parking deck buried below an expansion

of Crawford Square with loft houses, and the restoration of the

New Granada Theater and the Crawford Grill.

- Make Wylie Avenue a key pedestrian connection to downtown,

where you actually walk right through the arena civic space, learning

about old and new Wiley Avenue as you go. The path would continue

through a new park surrounded by state-of-the-art, mixed-use buildings

with large floor plates.

- Rebuild Fifth Avenue into a strong, pedestrian- and transit-oriented

place that emphasizes historic façades and high-quality

Modern infill urban construction for the new economy, emphasizing

small businesses and relationships to higher education.

- Make sustainable design, innovative urban design, and historic

preservation the anchors, to compete for people wanting authentic,

different places to live, work, and play. Divert storm-water runoff,

build geothermal fields, create new public open space, and inspire

new park-front property development.

This is only a set of ideas. You the reader must transform it, mess

with it, and make it truly a product of community collaboration! |