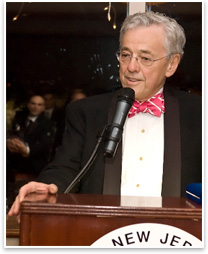

| J. Robert Hillier, FAIA

Education: I went to Princeton undergraduate and then continued on into graduate school at Princeton. I have an MFA and a BA in architecture. Early professional career: I went to work for a design-build company that designed projects and constructed probably half of those. It was phenomenal training, because I learned about how buildings are costed out and was therefore able to make sure when I started my own practice that every project could meet the budget. I was right out of school, but I was the lead designer because it was a small firm. Fortunately, the owner of the company took me under his wing and became a terrific mentor. He took me to every client meeting and presentation, so early on I was able to get a good taste of what it’s like to be an architect. The other partner in the company had a son who was about two years older than I. After three years, I realized that the plan was for the two of us to become partners, and I didn’t feel very comfortable about that. I had a dentist who had bought a wonderful Modern house and wanted to renovate it. His budget was $60,000 and the fee was 10 percent, so I was going to make $6,000. At the time, my salary was $6,000 a year so I decided it was a better deal to go out on my own. At 27, I started my own firm. Greatest professional achievement: Building the firm as a good, solid sustainable business. We’ve done a lot of really good design and I’m proud of all those projects, but I think the biggest source of pride is having built a firm that has tremendous employee loyalty and has been very much like a family and has been able to grow to 350 people, and now, since the merger [with RMJM in June 2007], to 1,100 people. Current focus at RMJM Hillier: To be candid, I was probably too much of a big personality [to continue managing the firm after the merger], and I think it’s better with the new partners that I simply focus on doing some major projects, which I’m enjoying very much. I don’t have any day-to-day responsibilities with the firm. My main job is keeping the clients I have happy and finding new clients. Dream project: I’ve got one really phenomenal dream project right now which is a senior housing project that I hope to design, build, and develop in Princeton. It’s along the lines of an Italian village in that it’s extremely condensed—it only uses 26 percent of the site and leaves the other 74 percent in its natural state. It’s going to be LEED certified, but it’s my dream project because I think it can be a forerunner to what housing ought to be for active adults and seniors. Not the usual corny Colonial stuff, but something really special. So far, we’ve got a waiting list of 25 people for 140 units, and that’s just from the newspaper articles. We haven’t even started marketing it. Hobby: One thing that I’ve been doing for 30 years—my wife calls it my Saturday job—is niche developments, where there’s an unusual architectural opportunity and also a chance to enhance the neighborhood and meet a market need. I recently did a new duplex, which we call an urban insertion. It was replacing a vacated derelict duplex in downtown Princeton. I teamed up with the family who owned the property and did the building with them as a development project. I’ve been doing development this way for about 30 years and have probably done over 200 housing units around Princeton. Best practice tip to colleagues: I think the key to success is that you have to be a good designer, you have to be able to sell good design, and you have to be able to sell yourself. They’re all bundled up together. I think that architects tend to be a little reticent about doing that, and because they don’t work at selling themselves and selling the design, they tend to resent the client because the client weighs in with opinions. The fact that they haven’t been able to sell their design is why the client is weighing in with opinions. I think too frequently a schism develops between the client and the architect, and architects need to know how to manage that. I think it’s the key. I had one old sage architect tell me that if you don’t have a client, you don’t get to do architecture. You’ve got to protect the clients, keep the clients, and keep the clients happy. You have to keep them happy not just by doing what they say, but by doing really great design and having them understand and endorse and embrace it. Sources of inspiration: The first inspiration was my professor in school, Jean Labatut, who taught me so much about the geometry of site planning and how to make sense out of things, especially in the site planning. The second inspiration was Ray Bowers, who was the architect who had the design-build business. He taught me how to keep it really simple for clients so that they get it, and if they get it they’ll go for it. The third was a developer named Herb Kendall who taught me the value of marketing. When I first started the practice, the AIA had rules whereby it was absolutely disdainful if you did any marketing. I still recall the time when I sent out a postcard to 300 of my closest friends that we had won a project in Rhode Island, and I was called in front of the AIA Ethics Council because I was doing advertising. When you look now, 40 years later, at the way marketing is done in the architecture profession, you realize what a huge change has taken place. It was Herb Kendall who taught me that you could be the greatest artist in the world, but the world won’t beat a path to your door unless you do some marketing. Marketing is everything from public relations to public speaking to making sure that everything that you’re doing gets known and that you get known. There are two other inspirations I should mention. First, I always have admired Skidmore, Owings & Merrill as a firm, and I wanted Hillier Architecture to be as much like them as possible. I admire them because they do great work. They’ve survived over 70 years and they have never lost their design presence or their design edge. In other words, they’re a big firm that never had to water down their design. The other inspiration is Norman Foster, who single-handedly has built a huge firm. The fact that he could take a high design firm and build it to some 450 or 500 people is pretty impressive. Reading material: I enjoy reading novels and socio-economic books like The World is Flat. Those kinds of books make a lot of sense, and I find a lot of my clients relate well to them. But, if there’s a good page-turner mystery, I’ll read that in a minute. |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Building a Brand

› Goucher Athenaeum Marks Place of Worldly Learning

For more information about the Michael Graves Lifetime Achievement Award, visit the AIA New Jersey Web site.

To learn about RMJM Hillier, visit their Web site.