Military Advanced Training Center Rehabilitates the Whole Body by Zach Mortice

Summary: Ellerbe Becket’s Military Advanced Training Center in Washington, D.C., offers soldiers recovering from amputee wounds suffered in Iraq and Afghanistan a variety of state-of the-art environmental simulators and gait-monitoring systems that help them regain their former abilities and re-enter civilian life. Spurred on by a rapid design and construction schedule, upcoming base closings, a modest budget, and the technically intricate and functional nature of the site, the architects opted for a simple and bare bones design.

On budget, ahead of schedule

This rushed schedule, modest budget, and the extremely functional programmatic details of the site pushed the facility's design towards unassuming simplicity. The rectangular 31,000-square-foot, two-story building is adjacent to the Brutalist tiered and shelved main hospital. The MATC’s low horizontal profile and matching beige tones make it seem as if it could be slid into the hospital’s horizontal volumes. A skywalk connects the top floor of the MATC to the main hospital’s prosthetics clinic. The courtyard below is shaded by the hospital’s cantilever. (The military’s now-scuttled decision in 2005 to move the entire Walter Reed campus to the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., by 2011, as well as revelations last February by the Washington Post of decrepit and substandard conditions on the medial campus both post-date the decision to build the MATC.)

The MATC gait lab uses a system of 23 cameras that record patients’ movements on six force-plate treadmills. While the treadmills measure how limb-loss patients alter their stride and apply their weight, the cameras record how the rest of their body moves, allowing therapists to deconstruct completely how amputees deal with missing legs and assemble personalized prosthetics and treatment regimens. A firing range simulator (equipped with some weapons altered for upper extremity amputees) lets patients re-establish their tactical skills. Scoville says that this feature is a boon even to soldiers who may not want to return to the military. “For some of them, there are psychological benefits to knowing that they’re capable of still doing their old job even if they plan never to do it again,” he says. “It’s a sense of self that you restore by allowing them to do that.”

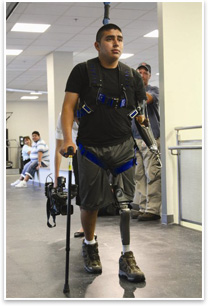

In these projected scenarios, therapists can add level after level of environmental stressors to test how well patients are able to cope with potential surroundings. To a typical urban streetscape, the therapists could “start adding cars and traffic, then we start adding cars that backfire—things that can trigger some PTSD [post traumatic stress disorder],” says Scoville. The top floor of the MATC is a large room with a 208-foot ceiling-mounted track walking system that runs along the perimeter. It harnesses amputees re-learning how to walk so that physical therapists don’t need to hover near them in case they fall. Long rows of windows flood the upper level with natural light. One end looks out to a gymnasium they’ll use when they leave. “That’s kind of the next step,” says Scoville. “They get the vision of the future.”

Lyon and Wilson are both deep into long stays (a typical amputee rehabilitation program is about a year long), and the vast majority of their time in hospitals has been at Walter Reed. It’s this type of adversity and the courage needed to move past it that causes Anglim humbly to downplay his own contributions to the project. It may not be architecture with a capital A, he says, but “it’s the environment inside that’s important.” |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||