| From Community Waste to Cultural Asset Tempe Arts Center rises from the ashes and celebrates the “Big Box” theory

Design influence

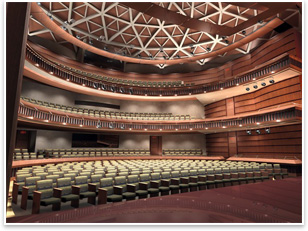

Adds Kane, “One of the big things we did conceptually was to create this large protective roof, and underneath that roof we have a series of venues almost like a little village based on Chaco Canyon Pueblo Bonito: that tight cluster that’s protected on three sides.” In Pueblo Bonito—as in Myers’ Seagram’s Museum—an outer protective wall holds the many rooms within. The spaces between the kivas, or performance rooms, served as the streets and plazas, or lobbies and corridors, for the village. Inherent site challenges

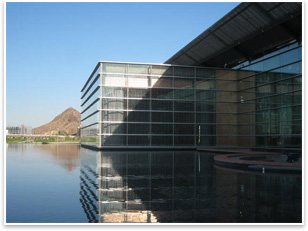

Myers believes that one of the most difficult things about designing a “theater in a park” is maintaining a high level of energy between acts, when people move out into the open spaces. “The worst theaters in my view are the ones that are in parks where everybody goes outside at intermission and you lose that energy and excitement that’s been built up in the first acts,” Myers says. To mitigate that loss of energy, “we pushed the theater close up to the lake and put a reflecting pond that reduced the amount of exterior space immediately off the theater lobby. That’s been very effective, so the lobbies are full of energy, and we don’t lose that dissipation to the outside.” The resulting 55,000-gallon, negative-edge reflecting pool creates a 300-foot-long waterfall at the north edge along Tempe Town Lake.

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Cultural Cornerstone Anchors Grand Rapids Revitalization

› Center for the Arts Will Shine in Sun Valley

› Warsaw Museum Focuses on Jewish History and Tolerance

John Kane notes that one of the interesting aspects of working on this project was its commitment to integrating public art. “Both of our firms and the city really believe in integrated art. They have a 1% for Art program, and they chose three artists to create four integrated public art pieces and one commissioned outdoor sculpture.” The entry marquee and fountain reflection wall were created by California artist Ned Kahn. The lobby carpet was woven by Hopi textile artist Ramona Sakiestewa. The fireplace, named “True North” was created by Mayme Kratz and Mark Ryan.

Design Team

Architect: ARCHITEKTON and Barton Myers Associates, Inc.

Structural engineer: Arup

Mechanical electrical plumbing engineer: Arup

Landscape architect: Design Workshop

Theater design consultant: Theatre Projects Consultants

Acoustic engineer/sound systems: Arup Acoustics (San Francisco)

Civil/survey/site structural engineering: Stantec

Geotechnical engineer: GEC

Lighting designer: Arup

Building envelop consultant: Simpson Gumpertz Heger

Life safety/ADA: Rolf Jensen Associates

Fire protection: Rolf Jensen Associates Arup Fire

Graphics/wayfinding: Adams Morioka

Cost consultant: Davis Langdon Adamson.

Renderings and photos courtesy Architekton and Barton Myers Associates.