| Inspired

by the Flag Fort McHenry’s new visitor center will lift all eyes to the Star Spangled Banner

The new Fort McHenry visitor center is designed to evoke the spirit of the American flag and the patriotism of that dramatic night. The new center’s sweeping, curved lines, building materials, and open interior spaces are meant to celebrate the birthplace of America’s national anthem and to educate and inspire its visitors. The center will focus visitors on the fort and the flag flying above it.

“The current building was built to handle 250,000 people annually. Now, we have 620,000 visitors, and as we plan for the War of 1812’s bicentennial, there will be a bubble of 750,000 visitors,“ says Gay Vietzke, superintendent of the Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. The current center cannot meet visitation demands, and last year 30 percent of school groups had to be turned away. “We wanted a building that gives visitors a positive experience, which sets the scene and gets visitors excited about seeing the real building itself,” says Vietzke.

GWWO also designed the new center to focus on the flag flying over the fort. “The building’s brick wall slopes upward, taking the eye up to the flag that flies over the fort. The visitor center and the flag are engaged in a dialogue,” says Reed. “We realized the flag was really the center of the story of Fort McHenry,” explains Reed, of discussions held with focus groups and the National Park Service, which runs the site. “We talked about what the flag means. Everybody has personal and emotional reactions to the flag.” The new building literally connects the flag and the meaning behind it in its own walls. The front elevation is composed of two walls differing in height and angles, one of brick and one of copper, representing the flag’s red and white stripes. The solid brick symbolizes the hardiness and valor associated with the banner’s red stripes. The thinner, more delicate copper façade expresses the purity and innocence associated with the white stripes. The difference in height and the opposing slants of the walls suggest a sense of motion, and as the copper wall recedes from the brick façade it directs the eye upward toward the banner. Landscaping design by Mahan Rykiel Associates of Baltimore complements the center’s curving lines with arcing pathways and paving patterns, along with plantings of differing heights that lead visitors to the entrance and then up to the fort. The drama of revealing the fort

“We tried to put people in the position of being Francis Scott Key,” says Bill Haley, partner and designer with Haley Sharpe Design of Falls Church, Va., and the United Kingdom. “Visitors go into this space and suddenly the space will transform into seeing the inspiration for Key’s poetry.” In the conclusion, the national anthem will play, and, beyond the windows, the fort and the flag flying above it will be revealed. “It makes it more dramatic and alive,” adds Haley. “At the end of the day, it’s a story that has a profound message—it is a powerful piece of poetry and music.”

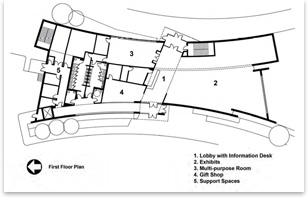

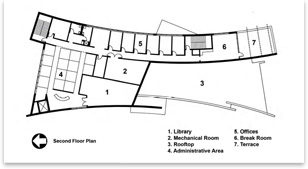

The center also features two entrances on opposite sides to accommodate visitors who arrive by land and by sea. A water taxi delivers 20 percent of the site’s visitors from the harbor, yet most visitors enter from the land side of the stronghold’s peninsula. To connect both entry points, GWWO created a lobby that runs through the building and that also frames the view. “Now, people can stand in the lobby and look down to where Francis Scott Key was,” says Reed. “In the future, park rangers will be able to point directly to where he was located.”

The new visitor center will be constructed outside of the cultural landscape, away from the 1814 reservation boundary, at the east end of the existing parking lot, and the present visitor center will eventually be demolished. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Mount Vernon Graciously Enhances the Visitor Experience

› Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center Provides a Museum Experience

GWWO has created visitor centers nationwide, including an orientation center and museum and education center at Mount Vernon in Alexandria, Va., the recently-opened Monocacy National Battlefield Visitor Center in Frederick, Md., and the Homestead Heritage Center at Homestead National Monument in Beatrice, Nebr. Haley Sharpe Design also has worked on master planning for the historic sites at Jamestown and Yorktown, Va.

Did you know . . .

The British invasion force that descended on Baltimore by land and sea in the summer of 1814 were flush with victory, having just sacked Washington, D.C., including burning the President’s Mansion. (Repainted to hide burn marks, it became the White House.) As her husband fled to Maryland, Dolley Madison relocated to The Octagon, where President Madison signed the Treaty of Ghent, supposedly ending the war, on December 24, 1814. The Battle of Baltimore was the turning point of the war, but the ending point was the Battle of New Orleans, January 8, 1815, in which General Andrew Jackson routed the British a month before the news of the treaty reached Louisiana.