| SUSTAINABILITY Putting All the Chips on Sustainability Summary: In our energy-consuming culture, is there anything more over-the-top than casinos? Arrayed in the Nevada arid climate, Las Vegas must rate as one of the least sustainable places on earth. For example, its inhabitants and visitors consume huge amounts of water in an environment where that commodity is particularly scarce—and a good part of it is used to raise grass in the desert. If there was ever a case for xeriscaping—the use of native plants and landscaping that can survive harsh desert conditions, it’s Vegas.

And the industry is starting to pay attention. A recent issue of International Gaming & Wagering Business magazine, a publication for those in the casino trade, presented the idea of sustainable casino development and operation as a bottom-line proposition. In other words, the color of money is the best reason for going green. Maybe this isn’t so surprising. Casinos, after all, are building types designed around the idea of maximizing the take. If sustainability can cut costs, it’s a sure bet.

Others savings might require casinos to rethink the psychology of the space they create. For instance, one of the traditional rules in gaming environments is to remove the customer from the outside world and its distractions. This usually translates into no exterior views—and little if any natural light. More natural light can cut lighting costs (and cooling costs, too, with fewer heat-emitting bulbs) but casinos will want to carefully consider whether outside distractions might reduce time on the gaming floor. The bigger message for architects about green casinos is that different clients consume energy in different ways, and some forms of resource efficiency can yield bigger jackpots based on how the client uses the building, and how the facility generates revenue. Sustainability has to be tailored to the client. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Michael J. Crosbie, PhD, AIA writes extensively about architecture and design and is chairman of the Architecture Department at the University of Hartford. He can be reached at: crosbie@hartford.edu.

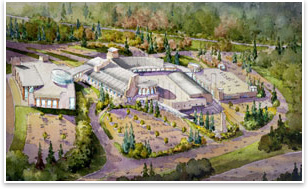

Green casino in New York

Green casino in New York Micro-turbines and natural light

Micro-turbines and natural light