Dallas’s West End Still Mending

by Jonathan Moore

Summary: With the renovation of the historic Old Red Court House nearly complete, along with a new nearby park, Dallas County is breathing life back into the area around Dealey Plaza—an effort that dates back to the 1970s renovation of the Texas Schoolbook Depository, a building with a history of its own. Summary: With the renovation of the historic Old Red Court House nearly complete, along with a new nearby park, Dallas County is breathing life back into the area around Dealey Plaza—an effort that dates back to the 1970s renovation of the Texas Schoolbook Depository, a building with a history of its own.

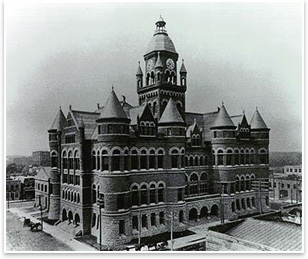

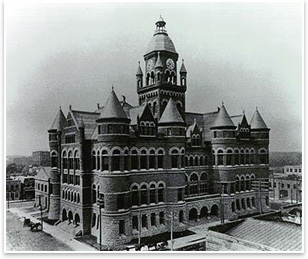

Old Red, as the courthouse is known, built in 1893 and designed by the Little Rock firm of Orlopp and Kusener, has long been a defining part of the downtown Dallas skyline. Now, with the replacement of its clock tower—removed in 1919 because of insufficient wind-load resistance—the building will once again pose its intended profile. It is also the venue for Dallas’s newest museum. The city’s most-visited museum, however, is just a bit down the street.

Even though it is more likely that Old Red was the last building President Kennedy would have noticed on that warm pre-Thanksgiving Day afternoon in 1963, it is the relatively nondescript Sixth Floor Museum, with its “sniper’s nest” exhibit that is the center of attention in this part of town. In the late 1970s, Dallas County began attempts to revitalize the West End area of the city by acquiring the Texas Schoolbook Depository, renovating it for office use, and creating an exhibit of that infamous sixth-floor corner area. It has since become one of the most-visited museums in Texas, says James Pratt, FAIA, whose firm worked on the renovation of the Old Red Court House. Even though it is more likely that Old Red was the last building President Kennedy would have noticed on that warm pre-Thanksgiving Day afternoon in 1963, it is the relatively nondescript Sixth Floor Museum, with its “sniper’s nest” exhibit that is the center of attention in this part of town. In the late 1970s, Dallas County began attempts to revitalize the West End area of the city by acquiring the Texas Schoolbook Depository, renovating it for office use, and creating an exhibit of that infamous sixth-floor corner area. It has since become one of the most-visited museums in Texas, says James Pratt, FAIA, whose firm worked on the renovation of the Old Red Court House.

That dark day in ’63

The Depository Building is almost unremarkable, save for its double-paired indented ionic columns and arched windows, which line the top two floors. But for the shots that rang out to begin the abrupt end to the Kennedy presidency, the name and building would be forgotten. Instead, they are forever seared into our national conscience. Constructed in 1901 as a merchandise showroom for the Southern Rock Island Plow Company, the Depository Building had encountered various stages of use. And, following the assassination, the building’s very survival was often in doubt as it became an architectural and civic symbol of a chapter in American history that left Dallas besieged with a torrent of unwelcome publicity.

More than a dozen years later, there was a grudging but palpable realization that the Depository Building’s legacy must be addressed. For any true healing process to begin, civic leaders and Dallas County officials realized that facts and emotions had to be dealt with honestly and openly. Private citizens and county officials realized that an exhibit would best convey the assassination story, not only as a random tragic event, but also placing it in the larger and often unpredictable historic context. The general agreement was that this site should be a unique educational exhibit. The building had survived a series of owners, several instances of vandalism, and public indifference before passage in 1977 of a local bond referendum secured the building for renovation. Adaptive reuse concepts were chosen to convert this building into dual purpose administrative offices for Dallas County (floors one through five) and a new Sixth Floor Museum (floors six and seven) chronicling the assassination. More than a dozen years later, there was a grudging but palpable realization that the Depository Building’s legacy must be addressed. For any true healing process to begin, civic leaders and Dallas County officials realized that facts and emotions had to be dealt with honestly and openly. Private citizens and county officials realized that an exhibit would best convey the assassination story, not only as a random tragic event, but also placing it in the larger and often unpredictable historic context. The general agreement was that this site should be a unique educational exhibit. The building had survived a series of owners, several instances of vandalism, and public indifference before passage in 1977 of a local bond referendum secured the building for renovation. Adaptive reuse concepts were chosen to convert this building into dual purpose administrative offices for Dallas County (floors one through five) and a new Sixth Floor Museum (floors six and seven) chronicling the assassination.

Creating a cathartic experience

“Denial is the antithesis of activity,” notes historian Conover Hunt in her book JFK for a New Generation. “The idea of providing interpretive text, photos and audio programs about the assassination at Dealey Plaza [became] an invitation to action.” A cultural historian and museum consultant for over 30 years, Hunt served as the Sixth Floor Exhibit’s first project director and chief curator. The team also included:

- Coordinating architects James Hendricks, FAIA, and Tony Callaway, AIA, (Hendricks & Callaway Architects), who worked on an add-on lobby space, visitor’s center entrance, and museum gift shop

- Preservation architect Eugene George, FAIA, reconfigured the sixth floor to its 1963 appearance

- Staples & Charles, Ltd., an Alexandria, Va.-based interpretative planning and design firm, coordinated and arranged the wealth of information into presentable exhibits.

The official opening of the exhibit was President’s Day 1989. “Cooperation and intellectual curiosity imbued every facet of this challenging project,” says George, a native Texan and preservation architect. George viewed the sixth floor as a system of static space. “The initial layout already existed,” he says.

A moment frozen in time A moment frozen in time

Taking advantage of the building’s proportion and scale, George retained a retro interior mosaic highlighted by original warehouse timbers, window frames, and brick walls. This allowed museum consultant Staples & Charles to achieve their goal of transforming 9,000 square feet of dead space into interpretative exhibit, documentary film, and audio space. One of the most eerie scenes, and a primary focal point for visitors, is the infamous sniper’s perch—an approximate 14-foot square glass-enclosed area along the corner front window facing the plaza below. Complete with replica boxes of textbooks, the area was re-created as it appeared when police and investigators arrived on the scene just minutes after the shooting. “The sniper’s perch reflects the ‘straight history’ approach we wanted for this museum,” Hunt says.

For Dallas, coming to terms with events beyond their control has had positive cathartic effects. “It’s an important facet of architecture,” George says, “a part of practice where design is instrumental in recreating history so future generations can better understand the past and how it affects us today.” |