| New York City Condominiums to Evoke Traditional Loft Aesthetic Through Modern Expression New luxury lofts in lower Manhattan’s SoHo district capture feel, fenestrations of bygone cast-iron era How do you . . . develop a condominium that combines a city’s architectural tradition with modern amenities? Summary: New York City-based Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects has designed SoHo Mews, a residential condominium in New York City’s SoHo Historic District, as a modern tribute to the distinctive cast iron architectural history of this revered location in downtown Manhattan. The two-building project consists of a nine-story structure and an eight-story structure, with a shared courtyard mews between each. The 175,000-square-foot project will offer 5,000 square feet of commercial space and 68 luxury loft units. Construction began last May. SoHo, New York’s historic “South of Houston” Street district, features 19th century buildings that were originally warehouses and factories. These structures have cast-iron facades with huge windows, some that even curved on building’s corners. Facades are both simple and ornate, and were designed in various colors and styles, including Classical, Renaissance Revival, and French Second Empire. Facade ornaments include Corinthian columns, elaborate segmented arches, dormer windows on rooftops, and bracketed roof cornices. Many of the SoHo facades are still today partly obscured by fire escapes installed during the early part of the last century, when mandated by the fire department. Steetscape facades are linked, a heavy signature of this Manhattan location.

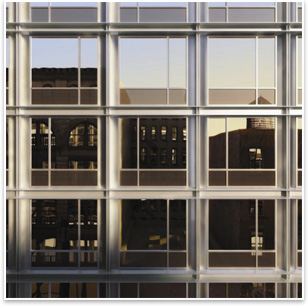

The irony of cast iron—its façade geometries hold up today The shifting of the vertical mullions provides articulation of movement and rhythm to the façade The bifurcated architecture of each building features a stone base, a gray curtain wall of metal panels, and recessed glass, expressing horizontal and vertical channels of floor slabs and columns. While the use of metal cladding on each building gives a modern twist to the SoHo façade, it also recalls when SoHo’s modular fenestrations evolved from cast iron to extruded metal to allow for more glass. The façades divide into two unequal zones of four and three bays, with a slightly off-center middle zone of two window bays. The shifting of the vertical mullions from bay to bay and floor to floor provides articulation of movement and rhythm to the façade, casting plays of light and shadow against clear, frosted, and fritted glass. The windows, storefronts, and entrances of SoHo Mews will also be divided by the structural channels to evoke the district’s historic buildings.

The Soho Mews interior—a grand experience “There’s no place like SoHo. It’s a wonderful place.” “SoHo Mews will be a place for less traditional living,” says Charles Gwathmey, FAIA, Gwathmey Siegel and Associates principal. “Its design is based on the ideas of the artist’s loft, the varied and rich physical scale and architectural massing of a neighborhood, and the dynamic life of the streets. There’s no place like SoHo. It’s a wonderful place.” | ||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Residences that Offer Maximum Pleasure, Minimum Bother

› Update on Condominium Liability Laws

Photo © ArchPartners 2007.

Did you know . . .

• SoHo’s cast iron buildings were built by many architects. Cast iron’s fire-resistant properties, during a period of major urban fires, and tensile strength made it possible to erect large building facades at less cost than comparable stone fronts with speed and efficiency.

• Cast iron is an alloy with a high carbon content that makes it more resistant to corrosion than either wrought iron or steel.

• Green Street in SoHo has the highest concentration of cast-iron facades in the world: 40 buildings on five SoHo blocks.

• The E.V. Haughwout Building in SoHo was a symbol of cast iron’s innovative use. Built in roughly a year’s time, it was home to what The New York Times called “the greatest china and porcelain house in the city.” When the Haughwout Building opened in 1857, it showcased New York City’s first passenger-safety elevator.