| Best Practices Innovation in Design for Aging Requires Shared Vision

Summary: In Design for Aging Post Occupancy Evaluations, a new book evaluating lessons learned from projects featured in the AIA’s last four Design for Aging Facilities Reviews, authors Jeffrey W. Anderzhon, Ingrid L. Fraley, and Mitch Green discuss the consensus planning process necessary for incorporating innovative design elements that will allow people to age in place gracefully. Innovation in Design for Aging Requires Shared Vision The evaluations in Design for Aging Post Occupancy Evaluations were done on structures that were fully vetted, through rigorous processes, by both owner and architect, and with justifiable reasoning behind decisions and compromises made. Still, it is unfair to make broad generalizations on the basis of these evaluations alone.

Generalized common evidences A certain inner strength is necessary within the champion if an innovative project is to come to fruition and be successful. It is far too easy to fall back on traditional solutions that have served well in the past and to take comfort in the belief that such a solution will continue to serve residents in the future. True advancement in care provision programs and environments is the result of thinking beyond traditional limits and embracing a passion to take something that has been done well and make it even better. It should also be noted that the presence of a strong advocate or champion can also quickly lead a project astray, especially if that person is unwilling to understand fully and systemically the ramifications of a wrong-headed decision. This usually coincides with a reluctance to admit that the approach may indeed have been wrong-headed.

Consider the implications of innovation Time is money. Without question, quality and innovation take time to envision and bring to reality. In our economically driven work, time translates quickly to resources, and preparation is the passport for this journey. The innovations highlighted in this book were accomplished with a great deal of preparation time in research and in thought about the correct course of action to ensure full value gained from the committed resources. This is not to say that successful innovation cannot occur on an accelerated schedule, only that the innovative thoughts should be completely researched, fully formed, and well considered. Within a collaborative environment, this can be accomplished expeditiously, and innovations can be tested by all involved and completed in a timeframe that incorporates a comfortable and affordable build-out schedule. Conclusion 2: Allocate the time to form fully the vision and collaborate with those who will move that vision into reality. Test the vision, or specific parts of the vision, in an existing environment to discover and address any implementation challenges or unforeseen consequences that arise.

Care innovations are often overlooked. A partially subsidized lunch for staff goes a long way toward improving morale, for example. Implementing “to the table” service provides an opportunity for residents in assisted living to see, smell, and select menu items, thereby increasing resident satisfaction and caloric intake. The presence of a concierge not only provides additional social service but also by strengthening person-to-person relationships, improves the staff’s ability to see and sense when something is wrong or someone is ill. Employee relationships can benefit from a department of “people and culture” rather than human resources in which increased ethnic diversity, cultural difference, and communication techniques are recognized and used rather than ignored. Conclusion 3: Innovations do not have to be expensive, only sensible. Specific issues

And most importantly:

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Lessons from the Latest Design for Aging Review

Reprinted from Design for Aging Post-Occupancy Evaluations: Lessons Learned from Senior Living Environments Featured in the AIA’s Design for Aging Review, authors by Jeffrey W. Anderzhon, AIA; Ingrid L. Fraley, ASID; and Mitch Green, AIA, and published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

To purchase Post-Occupancy Evaluations ($63 AIA members/$70 retail) visit the AIA Book Store.

For information on the AIA Design for Aging Knowledge Community, visit their Web site.

Captions:

0605p_bp2: Colorado State Veterans Home at Fitzsimons by Boulder Associates.

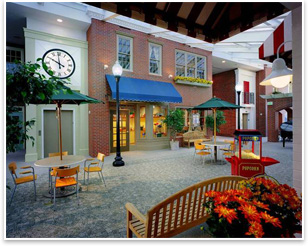

0605p_bp3: The Main Street at The Village at Waveny Care Center, an indoor town center inspired by downtown New Canaan—note the easily read clock tower. Photo courtesy RLPS Architects/Larry Lefever Photography.

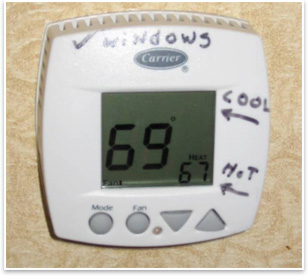

0605p_bp4: Innovation without user integration necessitated scribbled signage to explain how to use a digital thermostat. Photograph by Jeffrey Anderzhon.

How do you . . .

How do you . . .

Conclusion 1:

Conclusion 1: Make innovation sensible

Make innovation sensible