| |

Best Practices

Lessons from the Latest Design for Aging Review

Summary: Designing

communities for people in their retirement years is especially challenging,

notes AIA President Kate Schwennsen, FAIA, in her foreword to the

newly published AIA Design for Aging

Review. “Environments

for our aging population can support the intense, active lives desired

by this increasingly large portion of the U.S. population.” She

joins with other design-for-aging experts to offer 21 guiding principles.

“Those of us who design and develop

these communities must follow principles common to all livable communities,” Schwennsen

encourages, offering five: “Those of us who design and develop

these communities must follow principles common to all livable communities,” Schwennsen

encourages, offering five:

- Design on a human scale, allowing residents as much independence

as possible

- Provide choices and variety in paths, programming, unit types

and sizes, and community programming to create lively neighborhoods

and accommodate residents in different stages of their lives

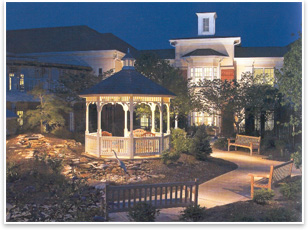

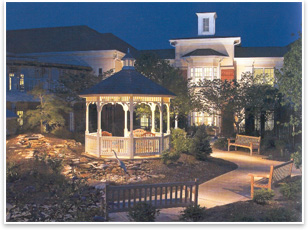

- Include vibrant public gathering spaces to encourage face-to-face

interactions, celebrations, and resident participation

- Create neighborhood identity, a sense of place that is unique

to the particular environment; larger communities often contain

multiple identifiable neighborhoods, encouraging ownership and

easing wayfinding

- Make design excellence in site planning, space planning, materials,

technology, construction methods, systems design, and all other

means at the architects’ disposal, “the foundation

of successful and healthy communities.”

Principles of scenario and strategic planning

“We must look to the future in a more disciplined and visionary

way,” continues William L. Minnix Jr., DMin, president and CEO

of the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, in

his foreword to the Design for Aging Review. “Using principles

of scenario and strategic planning, AHA is advancing its vision of

affordable, ethical aging services through articulation of what we

call Five Big Ideas that can transform aging services in the near future.” These

goals are to:

Innovative design is important to achieving these goals

- Expand managed caring

- Reinforce housing with supportive services

- Enable technology applications

- Transform the culture in nursing homes

- Manage the transition of elders.

Innovative design is important to achieving these goals, Minnix

stresses. Expanding skill sets entails every member of the design

and construction team devoting themselves to “a common vision

of education, research, regulation, and practice.” Supportive

services are key to consumers’ desire to age in place, which

can be enhanced by technological innovation, he adds. Transformation

of culture includes conscious creation of small-scale neighborhoods. “Private

and communal space and the familiar features of home, for instance,

can foster a sense of community life,” Minnix writes. Innovative design is important to achieving these goals, Minnix

stresses. Expanding skill sets entails every member of the design

and construction team devoting themselves to “a common vision

of education, research, regulation, and practice.” Supportive

services are key to consumers’ desire to age in place, which

can be enhanced by technological innovation, he adds. Transformation

of culture includes conscious creation of small-scale neighborhoods. “Private

and communal space and the familiar features of home, for instance,

can foster a sense of community life,” Minnix writes.

“In addition, we can help frail older people navigate through

the acute care, post-acute care, and long-term care systems and improve

their transitions by applying design concepts that support and improve

life and by facilitating efficient staffing, information systems,

and communication.”

Evident trends in senior living Evident trends in senior living

The Design for Aging Review jury statement introduces trends that

emerged in general from the projects submitted, which, they say,

represent several movements in senior-living design and care models:

- Growing use of sustainable building design strategies, particularly

those that affect health outcomes; clients, as well as architects,

are increasingly interested in sustainable design

- Further development of the house, household, or neighborhood

concept to reduce scale and provide a residential care model; in

addition, architects and clients address the scale of spaces in

community buildings

- Redefinition of services to reposition facilities for current

and future markets (e.g., offering diverse dining experiences that

mimic typical retail options)

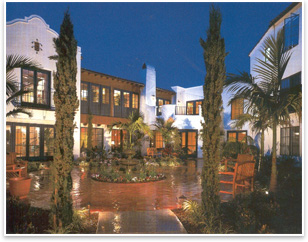

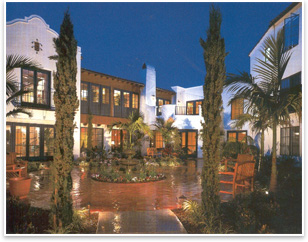

- Blending of local culture and geography with the building design

(e.g., providing a wine tasting room in a facility located in

wine country)

- Repositioning of continuing care retirement communities to respond

to changes in care models and financial arrangements (e.g., different

expectations from different generations of seniors, resident

ownership vs. deposit arrangements)

- Use of a Main Street design approach to provide variety to retail,

dining, worship, hair salons, and other services offered within

a continuing care setting

- Incorporation of technology in meeting resident needs (e.g.,

electronic records, wireless computer systems, systems to support

differently abled populations, and monitoring systems that allow

residents to remain independent for as long as possible)

- Design of senior living projects to accommodate community-based

services, making it possible for the community at large to participate

with seniors and vice versa, as residents choose

- Adaptation of outdated facilities to support new care models

and provide physical environments on a smaller, more residential

scale

- Integration of exterior architectural elements with interior

design and function through design team collaboration from the

project’s

onset

- Use of exterior spaces, such as gardens and covered porches,

as elements for organizing the design (reflecting the importance

of integrating building interiors and exteriors).

In conclusion, the jury expressed its wish that designers of facilities

for an aging population “continue to address factors such as

the cultural transformation of long-term care; evidence-based design

initiatives; connection to the community at large; the need for affordable,

mixed-income communities and services; and the need for creative

rejuvenation of outdated facilities and care models.”

|

|