Best Practices

The response for many firms has been extensive overtime, a marked increase in average salaries, and less experienced employees promoted early to management level positions. This issue spans the breadth of our industry, and more and more owner, architect, and contractor project managers are running projects for the very first time. Most participants in the developmental, design, and construction business today are experiencing some form of “Walk before you crawl” (or at least walk not long after you crawl) scenario in their offices today. The overall result in some cases is understaffed project teams, with limited experience, struggling to keep pace with project demands. For clients this may result in owner representatives with less experience at managing building programs, understanding construction costs, and working with architects and contractors. Contractor project managers may have less experience at preparing the contractor’s work plan and directing or coordinating the subcontractors. The design professional’s project manager may struggle with document completion and coordination, or coping with client expectations.

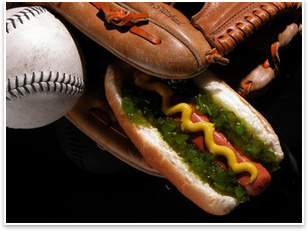

Good news, bad news This article is about ways to cover your bases in these days of increased work and limited employees. We will examine alternatives for improving your work production with your current staff, ways to outsource your work, and ways to minimize future layoffs. Don’t be bashful about evaluating these options and testing them in your firm. You are not alone in your workload status, and your competition is likely already using some of these alternatives. Also, do not be bashful about suggesting alternatives we may not have considered or of offering criticism of those we have. The hole in the workforce But the new work did not come. Times would be lean for several years. Around our town, hundreds of architects and interns lost their jobs, and that devastation replayed through the cities of our nation. Everyone was touched: owners, architects, and contractors alike. From the early to mid 1990s, the industry hired very few employees, some firms continued layoffs in their struggle to survive, and some firms did not survive. Many promising employees sought alternative careers just to have a job. As a result, managers who would have been hired and trained during that time would now be 10-15-year veteran managers who could handle a large or complex project. The recession of the early nineties continues to impact the profession because today, when we desperately need this talent pool, they are not here in the numbers we need.

We all face today’s busy times with a hole in the workforce. Owners, architects, and contractors struggle to maintain this vital management element. Competing firms steal from each other in hiring wars that only serve to drive up base salaries. For all participants in the design and construction industry, this mid-level manager is the most sought after employee. Alternatives

Everyone is now being forced to make decisions about how to cope with the strain on the workforce. The easy way out would be to stop taking on new work, but this approach does not conform to the mindset of our feast or famine industry. The natural response is to keep taking on work and then worry about who is going to produce it. After all, we have always managed to get the work done somehow, haven’t we? Positive action Communicate closely with your client. Products of these working conditions can include missed deadlines and incomplete or uncoordinated work, which can result in owner frustration and disappointment. On the other hand, most clients will understand if you keep them closely informed of your work status. A client who does not know who’s on first on their project will be less confident about the working relationship and may be more difficult to satisfy. Owner expectations may also be more difficult to manage during these times. If you have to tell a client you are going to miss a deadline because you are understaffed, early is better than later, because bad news does not get better with age. Focus on your employees. Strive to improve overall employee comfort level. Everyone wants optimum performance from their staff every day, but when workload is up and staffing levels are down, higher employee comfort and satisfaction can help offset demanding schedules. The long working hours that are required can be tempered with amenities to soothe and reward. Historically, firms have offered unlimited coffee and tea to employees, but lately firms have added baskets of fruit by the front door for employees to snack, gourmet coffee and tea service, chair massages, and the like. One architect came up with an afternoon tea break with warm moist towels to refresh.

Plan for the future. Get serious about training. Although training should be a continuing concern, it is especially important when you are asking less experienced employees to take on assignments for the first time. AIA member surveys have consistently indicated project management training as one of the most requested topics at conventions and conferences. Training is available through the AIA eClassroom and many of the larger firms are contracting with training companies to provide management and leadership training on a continuing basis. Project manager boot camps designed specifically for architects are available from several sources. Larger firms are moving past the basic human resources structure to organization development. This program takes employee needs to a higher level by including HR, skills, and leadership training and employee performance assessment into a coordinated strategic initiative. This approach has existed for many years in large blue chip corporations, and the design and construction industry is now discovering its applications and benefits. One firm’s initiative is called, People and Organization Development, and it is designed to improve all employees throughout their working experience. A curriculum has been developed for each job description so that skills training are better understood and career paths are more visible. A curriculum was also developed for future leaders, which include management and leadership training. A shorter-term improvement that can assist in maintaining management quality is to stack your management structure. A strong, experienced project manager with lesser experienced managers assigned to them can oversee more projects through monitoring, mentoring, and teaching. This approach can be effective for all participants under all industry conditions, and it is reminiscent of the old chief draftsman whom we talked about last month. Going outside

Workforce levels tend to follow workload, and, in busy times, many practitioners find themselves scrambling to balance the two. Since tapped-out employee resources tend to reduce the chances of walk-in candidates, a stronger program for employee recruiting is often pursued. Architecture schools produce a consistent and predictable workforce at the entry level, and structured school visits and recruiting can be beneficial. Larger firms use school recruiting for summer internships, which can facilitate full-time job offers at graduation time.

A potentially more benevolent approach to staffing is employee sharing. Firms in the same geographical area with differing work loads have been known to loan out employees. This retains their employee through lean times while benefiting the other firm with an experienced, temporary employee. It is advisable, however, that the two firms be good friends and have the same work philosophy. (For more on strategic alliances, read chapter 6.3 in The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 13th edition, a synopsis of which is available on AIA.org.) All of these staffing approaches can benefit from the assistance of a strong human resources department, and recruiting typically at least touches a part of HR and organization development. Yet another option is the use of consultants. Another architecture firm can be used to share in the work. However, unless the firm was proposed at the onset, consideration should be given relative to the owner’s awareness of the team makeup. If the entire workforce is severely depleted, as is the case in many U.S. cities, some of these ideas may not be workable, which leads us to another emerging option. Going further outside More than 35 invited experts, practitioners, AIA leaders, and representatives of organizations and software companies aired questions, shared perspectives, and discussed the challenges.

Findings and recommendations of the AIA Offshore Outsourcing Roundtable were published in a report that is available from the AIA International Committee Web site. Steps to control workload Go, no-go marketing. When your workload exceeds your labor capacity, it is wise to focus your marketing strategy on those projects for which you are most qualified and on which you are most proficient and profitable. Times such as these are not always best for exploring new markets. Some firms have developed “go, no-go” criteria to concentrate their efforts on the most reasonable commissions. Such measures can include minimum project size, specific locales, specific building types, or repeat versus new clients. One firm with a high repeat client percentage decided to work only for their existing clients unless a new client’s project was a preferred project type, a minimum size, or included broader market area potential.

Increasing fees. Some firms have increased fees in a polite attempt to avoid turning down a commission, and stories abound of clients having accepted the higher fee without complaint or hesitation. This has resulted in an opportunity for many owners, architects, and contractors to experience increased profits, but it has done little to help manage workloads. On the other hand, the higher fees have helped soften the blow of increased overtime work and rising salaries. Extending delivery times. Some firms have taken the direct approach and have quoted extended delivery times, either by setting a later start date or by increasing the amount of time required to produce the work. Historically, when a developer, architect, or contractor has been awarded a commission, the expectation is that the work will commence fairly soon. If staff is not available to start “soon,” then repositioning the project’s start or completion time may be the only reasonable way a firm can accept a new commission. Turning down work. This option tends to run counter to the culture of architects who have endured the “feast to famine” reality of the design and construction business. Nonetheless, in this time of limited resources, saying no to a new project may be the only viable option. Many architects come from a background of “never say die,” and, like us, are struggling to cope with a business environment where turning down a new project can ever be a viable option. We know that we are not alone with our feelings. However, we are confident that many of you have considered or will consider projects that you probably should turn down because of your workload. Even if, “…we have always managed to get the work done somehow, haven’t we?” Conclusion

These challenging conditions will visit us from time to time as they did in the early to mid seventies when few architecture graduates could find jobs, and again as they did in the mid-eighties and early nineties when layoffs were the rule. But since we have had a strong economy and plentiful work for more than a decade, a large portion of our work force has never felt the sting of “famine.” We have presented a few options for managing these busy times, and we hope you find them helpful. But be forever mindful that change is always on the horizon, and those ideas may morph with other concerns and present new challenges. What challenges? Will the workload of today perpetuate and become a way of life? Many of us have been looking for signs of a turndown in work for years, and as we write this article, it does appear that signs are on the horizon. Of course, we may only be seeing what we wish to see. Mixed in among the challenges of delivering today’s work and looking out for tomorrow’s work is the certainty that BIM and integrated practice are going to alter not only how we deliver our services, but our relationships with owners and builders as well. Metaphorically, these can be confusing times. Who’s on First? Naturally! As you sign the owner-architect agreement for that new project and ponder, maybe even worry a little, about how you are going to cover your bases, be grateful that it is a time of feast, take comfort that you are not the only one facing the same or similar challenges, and remember to be careful out there. This series will continue next week in AIArchitect when the subject will be name of April article here. We will … etc. If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk- or project-management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them through AIArchitect. James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS Architects. He serves on the AIA Risk Management Committee and he chaired the Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 14th edition Revision Task Group. Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, has served as a project delivery leader for several international firms where his responsibilities included construction documentation, project management, and loss prevention activities. He serves on the AIA Practice Management Advisory Group. This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions and illustrations apply to specific situations. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Raiders of the Lost Art: The Vanished Treasures of Architecture

› Top Gun: Targeting and Resolving Problematic Issues

If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk- or project-management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them through AIArchitect.

James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS Architects. He serves on the AIA Risk Management Committee and he chaired the Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 14th edition Revision Task Group.

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, has served as a project delivery leader for several international firms where his responsibilities included construction documentation, project management, and loss prevention activities. He serves on the AIA Practice Management Advisory Group.

This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions and illustrations apply to specific situations.

A reality in the design, development, and construction industry is that we are only as good as our project team. Accordingly, we strive to assign and staff our projects in a way that will be most beneficial for the client and the scope of work. However, in this extended active economy, available personnel for owners, architects, and contractors alike have been significantly tapped. Even the small practitioner who relies on occasional contract labor may have difficulty in finding help when that larger commission arrives.

A reality in the design, development, and construction industry is that we are only as good as our project team. Accordingly, we strive to assign and staff our projects in a way that will be most beneficial for the client and the scope of work. However, in this extended active economy, available personnel for owners, architects, and contractors alike have been significantly tapped. Even the small practitioner who relies on occasional contract labor may have difficulty in finding help when that larger commission arrives. Meanwhile, those of us involved with risk management are waiting for the inevitable ballooning of claims that has happened in the past when such conditions were experienced.

Meanwhile, those of us involved with risk management are waiting for the inevitable ballooning of claims that has happened in the past when such conditions were experienced. The damage from this unfortunate event was exacerbated by the emergence of CAD. These managers would have developed their careers on the computer, and they would be mentoring and teaching younger CAD operators how buildings go together. Their absence plays a part in why the experience quotient in our profession has turned upside down as we espoused in the August 2005

The damage from this unfortunate event was exacerbated by the emergence of CAD. These managers would have developed their careers on the computer, and they would be mentoring and teaching younger CAD operators how buildings go together. Their absence plays a part in why the experience quotient in our profession has turned upside down as we espoused in the August 2005

The

The  With your existing clients, you might wish to pursue those who value you and your services most highly and decline those who reject the concept of brand loyalty or who have been historically difficult to work with.

With your existing clients, you might wish to pursue those who value you and your services most highly and decline those who reject the concept of brand loyalty or who have been historically difficult to work with.