08/2005

Your Grandfather’s Working Drawings

by Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, and James B. Atkins, FAIA

Architects and their instruments of service have become a target for disputes and litigation at an increasing rate in recent years. Rarely is there a major project where the drawings and specifications are not subjected to scrutiny by parties claiming to be harmed by the documents or looking to find a source of harm within them.

Design professionals are greatly challenged by this turn of events, and we ask why and how it is happening. What has changed about architecture and our services? Do professionals have fewer skills than in years past? Or is it that contractors are not as experienced or skillful and thus unable to build from architectural drawings? Are CAD drawings inherently less thorough than documents of the past? Perhaps the appearance of accuracy implied by CAD has changed owners’ and contractors’ expectations? Or is it that there are simply too many lawyers?

This article will explore the profound impact of CAD on the

way that our drawings are produced today. It will begin by looking at

the purpose of our drawings and their intended use. It will examine the

management void left by the change from manual artistry to digital

and its effect on our work product and how it is perceived and used.

It will conclude with suggestions for what firm principals and managers

can do to bridge this gap and improve how the work of architects

is perceived.

This article will explore the profound impact of CAD on the

way that our drawings are produced today. It will begin by looking at

the purpose of our drawings and their intended use. It will examine the

management void left by the change from manual artistry to digital

and its effect on our work product and how it is perceived and used.

It will conclude with suggestions for what firm principals and managers

can do to bridge this gap and improve how the work of architects

is perceived.

These are not your grandfather’s

working drawings

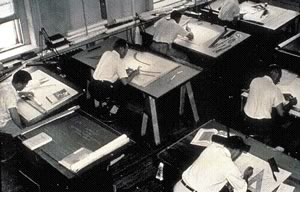

Baby-boomer architects may recall the drafting room environment of the

past. A common fixture was the chief draftsman. (They were called draftsmen

back then and not draftspersons as they are today.) The chief draftsman

reigned with an iron hand and a quick temper over the drafting room,

which later was renamed the studio. The documents used for construction

were called working drawings, and mastery of their creation was an

unending career objective.

Junior draftsmen, also referred to as cubs, were expected to keep their heads down and their tails up. They were expected to labor with precision and cleanliness over tracings made on Mylar or Clearprint 1000H drafting velum. The medium of choice was wax lead, or H and 2H graphite lead, or Rapidograph ink pens, and tracings were kept free of smears and lead buildup by using Pounce or other drafting powders. Their most useful computer was an Add-A-Feet Jr. that added feet and inches much like the ancient abacus. Baby boomer architects can also tell you war stories of having their hair lifted by a stern chief draftsman when mistakes were discovered in their work. The worst days for apprentice architects were the days when the chief draftsman reviewed and redlined their drawings. The rebuke was almost unbearable as the limitations of their professional skills were exposed for all to see, and often for all to hear.

If you find that this world seems alien and contrasts with your workplace

of today, then it is safe to assume that today’s products of service

are not your grandfather’s working drawings. Today, the strict

discipline that old-timers apprenticed under would likely be considered

harassment, and it might even be prohibited by law.

If you find that this world seems alien and contrasts with your workplace

of today, then it is safe to assume that today’s products of service

are not your grandfather’s working drawings. Today, the strict

discipline that old-timers apprenticed under would likely be considered

harassment, and it might even be prohibited by law.

Unfortunately, for all practical purposes, the chief draftsman has long become extinct. Working drawings today are prepared almost entirely on computers. Reverence for and possessive feelings about drawn construction document “artwork” seems to be vanishing, or possibly has already vanished. The intelligence of computer generated drawings has begun to replace the draftsman’s knowledge. Young architects serve their apprenticeship to their Dell, IBM, Compaq, or Sony. Details, instead of being constructed thoughtfully line by line, are pulled from recent projects or a library of existing details, then picked and dragged to a place on the computer screen. Redlines, when offered as a criticism of drafted work, are made on impersonal and disconnected “plots” and are transferred onto the electronic ether, bypassing the emotional importance of an ownership in a work of art. Criticism is presented to young architects with more thought of not offending than of teaching.

These days, senior project leaders, unable to comprehend fully the story of the building in the limiting context of a computer screen, and not usually proficient with CAD, rely on younger architects to do the drafting. They can no longer mentor and coach in the artistry of drawing organization and detail composition. This can lead to drawings that are issued for construction unchecked by more experienced eyes. The result all too often is incomplete, unworkable, or worse un-constructible designs depicted on drawings that must be revised to a sufficient and acceptable level of quality while under fire on the job site. It is not always clear who is teaching whom about the technical arts in architecture. It appears that, in a number of cases, the experience quotient has essentially turned upside down.

How about them Apples? . . . or Dells? . . . Or Sonys? . . . The computer emerged as a great solution to the laborious manual endeavor of crafting our designs line-by-line on a two-dimensional surface. CAD opened the door for infinite reusable backgrounds and detail libraries. Today we have virtually instantaneous transfer of drawings through the Internet. But, unfortunately, with these innovations came isolation. All too commonly, we no longer have one-on-one discussions with a supervisor even as the apprentice architect crafts the wall section. We no longer discuss the reason that the flashing must terminate where it does, or why the caulking is placed as it is. Change, a thought-filled and laborious endeavor in a hand-crafted tracing, is now widely thought to be accomplished with the casual push of a button. The result is a serious disconnect in our intellectual transfer. The universal knowledge of our firms is sitting dormant as the youngsters surf and select, pick and drag and cut and paste.

We should try to reconnect the circuit. Try to re-establish intellectual

communications among ourselves. To do that we must begin by going back

to one-on-one learning opportunities, taken advantage of at the point

of need; at the drafting table, or the modern equivalent thereof. We

must stop worrying about the perpetual receipt of emails through our

Blackberries and whether our phone mail greeting is current. There are

more important things. Things like taking the time to sit with the young

architects, our apprentices, to talk about the basic elements of our

documents and how they are used.

We should try to reconnect the circuit. Try to re-establish intellectual

communications among ourselves. To do that we must begin by going back

to one-on-one learning opportunities, taken advantage of at the point

of need; at the drafting table, or the modern equivalent thereof. We

must stop worrying about the perpetual receipt of emails through our

Blackberries and whether our phone mail greeting is current. There are

more important things. Things like taking the time to sit with the young

architects, our apprentices, to talk about the basic elements of our

documents and how they are used.

The purpose and effect of documents

A valuable exercise is to gather the staff over lunch and get back to

the basics by discussing the fundamental purpose of construction drawings.

One way is to begin by making lists of the simple things. Emphasize

the idea that working drawings should depict the building design in

its final desired form. Prepare your cubs by explaining the Architect’s

Handbook of Professional Practice position that working drawings are

not intended to be a complete set of instructions on how to build the

building. Even so, the drawings must explain the design concept thoroughly.

The “water runs downhill” approach is a good way to have fun beginning at the base level. Encourage questions about building systems and details. CAD or manual, the building system is the same. Explain that projects go more smoothly and clients are happier when the final scope of the project is adequately represented in the drawings and specifications.

Take your cubs to the job site. There is nothing more instructive than the work itself. Copy them on Site Observation Reports and explain site conditions requiring an answer to a Request for Information from the contractor. More importantly, explain what was not adequately expressed in the documents that would have prevented the RFI in the first place. Let them develop their own answers to an RFI. If you have been involved in a lawsuit, let your cubs read the Plaintiff’s Original Complaint or the Defendant’s First Set of Interrogatories.

The

purpose of these exercises and discussions is to let the gravity of the

purpose and effect of working drawings settle upon the people who are

preparing them. These are the essential lessons that were so personally

and effectively conveyed by the old chief draftsman; the lessons that

modern young architects desire and need, but to which they are less and

less exposed because of our impersonal digital environment.

The

purpose of these exercises and discussions is to let the gravity of the

purpose and effect of working drawings settle upon the people who are

preparing them. These are the essential lessons that were so personally

and effectively conveyed by the old chief draftsman; the lessons that

modern young architects desire and need, but to which they are less and

less exposed because of our impersonal digital environment.

The relationship of drawings and specifications

The relationship of working drawings and specifications is too often

misunderstood. The specifications help define the quality of the materials

and systems to be used in a project. The drawings help define the layout,

location, and quantity of the primary elements and materials in a project.

Even so, the specifications may list the quantity of certain elements,

such as the number and type of fasteners to be used in a particular

assembly.

It is general practice today to not use a specific manufacturer’s name or product model number on the drawings, leaving that information to be indicated by the specifications. However, the preparation of construction documents is a matter of individualized professional judgment, and this rule should be bypassed if the professional feels it necessary to provide a more clear and understandable message in the drawing. Nevertheless, drawings are an incomplete story without the companion specifications.

The functional use of working drawings

The best way to address the functional use of working drawings is to

first look at how and for what purpose drawings are used in each phase

of services. Although drawing phases tend to be blurred by CAD and

will be so even more by BIM, understanding drawings by phase is essential.

Schematic design phase. The primary purpose of schematic design drawings is to explain the design concept to the owner. Although the design is not yet entirely represented, the schematics can demonstrate basic spaces and relationships. Due to the elemental aspects of this graphic illustration, the architect will need to explain verbally what is not apparent to the owner. This will require paying close attention to the owner’s reactions and asking confirming questions.

For the architect, the schematic design drawings are often a catalytic influence for further exploration of the design concept. Finally, these drawings may provide the contractor or estimator with a basic scope for formulating a very rough cost estimate. The overriding function of schematic drawings, however, inures to the benefit of the architect and owner.

Design development phase. The purpose of design development drawings is to focus in the design more of the technical aspects of materials and building systems. Although this phase allows the architect to finalize space and function to a great degree, the primary achievement is to enable the owner to understand how the project will function as well as give more detail about what it will look like. Again, this will require the architect to observe carefully the owner’s reaction and ask confirming questions.

A second beneficiary is the contractor who can become more comfortable with the scope of the building and proposed materials and systems. During this phase the architect continues to explore yet more refined design solutions.

Sometimes the purpose of design development drawings is misunderstood. Such as when owner’s expect them to serve as the basis for a “Guaranteed Price” or when architects use them as a beginning for construction documents. Design-development documents do not reflect the full story required for constructing the building and rarely can serve as the only base information for developing a complete “Maximum Price.” They may indeed serve as an efficient starting point for construction documents, but CAD technology creates the illusion of accuracy and completeness beyond their intended scope.

Construction documents phase. The audience for “working drawings” is the contractor, its subcontractors, and code enforcement officials. The purpose of construction documents is to communicate in detail the requirements of the design concept. The detail must be sufficient to allow the contractors that will build the project to implement their plan for pricing, contracting for, procuring, and placing the work.

The impact on budgets and schedules

Construction documents can impact project schedules in several ways.

One significant impact is that a reasonable amount of time is required

to prepare construction documents. In a traditional project schedule,

construction documents are prepared before construction is begun. When

owners desire to start construction earlier, they often request a shorter

construction documents preparation time frame or elect to fast track

the project.

Shortened

preparation times hasten the preparation of the documents and leave less

time for checking and coordination. Working faster causes speed-induced

errors to creep into the documents. Fast track project scheduling where

construction is begun before construction documents are complete can

also lead to speed-induced errors as well as scope gaps in the individual

partial packages of construction documents. Fast track delivery can also

be complicated by an owner’s desire to know the

estimated cost of construction before construction is started. It can

be very difficult to use packages of incomplete documents for defining

the ultimate cost of construction. Shortened or hastened time frames

carry increased risks for both the design professionals and the owner,

and frequently the contractors as well.

Shortened

preparation times hasten the preparation of the documents and leave less

time for checking and coordination. Working faster causes speed-induced

errors to creep into the documents. Fast track project scheduling where

construction is begun before construction documents are complete can

also lead to speed-induced errors as well as scope gaps in the individual

partial packages of construction documents. Fast track delivery can also

be complicated by an owner’s desire to know the

estimated cost of construction before construction is started. It can

be very difficult to use packages of incomplete documents for defining

the ultimate cost of construction. Shortened or hastened time frames

carry increased risks for both the design professionals and the owner,

and frequently the contractors as well.

The errors and omissions that are usually contained in construction documents can also cause the documents to impact the budget and schedule. Errors and omissions often cause unanticipated construction costs, which usually result in some element of delay or extended schedules. When errors and omissions are found in the documents prior to construction of a building element, there is less likelihood that the budget and schedule will be affected, especially if the contractor or subcontractor has not been selected. However, the negative impact of errors and omissions found during construction usually increases dramatically as the job progresses toward completion.

The “complete” documents

myth

There is no accepted industry definition of “complete” construction

documents. If such a definition did exist, it would obviously be a valuable

tool for architects, owners, and contractors. One reason that documents

cannot be complete is that projects tend to be one-of-a-kind creations.

Another reason is that the documents are conveying a design concept and

not a finite assembly. (In our next article, “Drawing the Line,” we

will explore the limitations of the architect’s drawings and the

additional information and work required of the contractor to actually

build the building.)

The uniqueness of an architectural project is the custom design and assembly of thousands, perhaps millions of parts and pieces incorporated into a project through a progressive series of strategic decisions. The preparation of architectural drawings is a process that is substantially infused with subjectivity. Although somewhat objective rules can be applied to some of the process, the majority of decisions and actions involve the subjective application of professional judgment, which varies from project to project, professional to professional, region to region, circumstance to circumstance, and time to time.

Accordingly, architects cannot prepare complete or entirely correct construction documents. What an architect can do is prepare documents that are sufficient for supporting the construction process. Incompleteness, conflicts, coordination miscues, errors, and omissions can and will occur in all documents prepared by human hands. The surviving discrepancies are corrected during construction through communications with the contractor, requests for information, and the change process.

We have reviewed in our past articles that a design professional cannot

be reasonably expected, and is not generally required by law, to provide

perfect services. Accordingly, an architect cannot be expected to provide

the undefined and indefinable perfect set of completed construction

documents.

We have reviewed in our past articles that a design professional cannot

be reasonably expected, and is not generally required by law, to provide

perfect services. Accordingly, an architect cannot be expected to provide

the undefined and indefinable perfect set of completed construction

documents.

The impact of CAD

An analysis of the impact of CAD on the preparation of architectural

construction documents would fill volumes. In this article we have

observed that CAD has essentially been a young architects’ game

since the onset of its application. The skills of creating graphic

architectural illustrations cannot be taught by industry elders as

it was during the time when your grandfather’s drawings were

prepared.

Another distinct disadvantage of CAD is the illusion of greater accuracy and completeness early in the project. Because of the crispness and the ease with which CAD allows architects to embellish documents, schematic design and design development phase drawings appear to contain information beyond their state of research and development. This appearance in turn causes owners and contractors to believe that the drawings contain information that allows uses beyond their limits.

Unfortunately, this illusion prevails with architects as well. Architects should be cautioned not to issue documents before they are sufficient for their intended purpose. Although schematic design and design development drawings may look very accurate and complete, and it may be easy to add a small modicum of information to increase this illusion, the reality is that they are not yet sufficiently developed for use as bidding or construction documents. Perhaps one solution would be to present our CAD schematic and design development phase drawings in “freehand” or “sketch” presentation mode to subliminally reinforce their conceptual nature.

Today, in the studio, you are as likely to hear discussions of controversy about layers, line weights, pen tables, and font sizes and styles in a drawing as you are to hear debate about the building details. These discussions come under the heading of “CAD Standards” and are viewed as so important that we not only have a national CAD standard but a host of others as well. In our drafting room of the past our drawings had just two layers, a front and a back. Our line weights and pen tables were limited only by the artistry of the draftsman. Our fonts, also the subject of artistry, were developed throughout a career and were a benchmark of personal pride. On a manual tracing prepared by more than one person, you might find two or more “pen tables” and more than one “font,” yet the drawing would be legible and useable. Time was spent learning and focusing on architecture, and not as much on CAD standards.

CAD drawings do, however, offer some very positive benefits. It is possible to achieve a much greater level of accuracy by drawing building elements at their actual size rather than drawing them to a scale, as required by manually prepared drawings. CAD offers the promise and fulfillment of speed in preparation and change unattainable with manual drawings. CAD also offers the opportunity to develop and store details that can be used on subsequent projects with great ease.

These details, sometimes characterized as standard details, or a detail library, can allow a younger team to apply the benefits of experience that otherwise may not be available. However, such standard details must be rigorously maintained for accuracy and current application so that they do not become outdated or are inadvertently used erroneously on repetitive projects. They must be touched periodically by experienced eyes.

When the manual draftsman drew a detail from the office standard files, the detail was completely recrafted on each new drawing and the chief draftsman guided and critiqued with each new use. Today, details are often picked and dragged from the detail library without sufficient scrutiny as to how and if the detail applies.

Back to the future

The matter of the upside-down experience quotient has had and continues

to have a significant impact on the preparation of working drawings.

However, this impact may resolve itself as the younger generations

of CAD-capable architects mature and move into positions of leadership,

assuming that newer generations of CAD, such as BIM, don’t continue

to turn the quotient upside down again and again and again. If BIM

develops to its apparent potential, the kind of knowledge required

to design and place virtual data and components in three dimensions

may actually improve the experience quotient. Firms have already found

opportunities to add senior architects to their 3D CAD studios to coach

in how a building goes together, since constructing a building in 3D

CAD benefits from a steady application of that knowledge.

For now, more experienced architects must make a concerted effort to

develop and modify their leadership skills and habits so that the transfer

of information and experience regarding the creation of working drawings

can occur with the same ease and effectiveness that it occurred with

our grandfathers. The goal should be future project leaders with the

skills and mentoring abilities of the old chief draftsman; skills of

divining and explaining, day by day, the quality and state of completeness

of the construction documents for which they are responsible.

For now, more experienced architects must make a concerted effort to

develop and modify their leadership skills and habits so that the transfer

of information and experience regarding the creation of working drawings

can occur with the same ease and effectiveness that it occurred with

our grandfathers. The goal should be future project leaders with the

skills and mentoring abilities of the old chief draftsman; skills of

divining and explaining, day by day, the quality and state of completeness

of the construction documents for which they are responsible.

Architects should also strive to review their documents in the same context as the audience who will be using them. Documents cannot be developed and checked solely on a computer screen if the contractors who will be using them on site will be working from paper copies. Someday, in the future, it may be that documents will be provided to the contractors on video tablets or through computerized goggles, and this requirement will no longer be necessary. But for now, checks and balances implemented through a paper medium should remain a part of our document development process.

Those who can remember back when CAD was emerging would likely never have guessed that such a wonderfully accurate and time-saving innovation would interfere with the age-old mentoring process. Nevertheless, we must confront the challenges and take action to restore the stabilizing transfer of knowledge and experience. Architects must endeavor to be more effective in passing on to succeeding generations their knowledge and experience on how buildings and systems go together. We must impart what we know through our years of experience to those whose primary contact with our profession is now through a computer screen.

Younger architects must be mentored by more experienced architects concerning the purpose for preparation of construction documents as well as how to understand and use the various components of the documents. And more experienced architects who may be less skillful in the use of CAD must endeavor to understand more thoroughly how construction documents are being digitally created.

Architects must also explain to owners and contractors that even under the most perfect circumstances the documents will be neither complete nor entirely correct. This reality must be explained in order for owner’s and contractor’s expectations of the architect’s instruments of services to be realistic. Under the best of circumstances documents will require clarifications and additional information to be suitable for construction. Just as they always have.

The basic model of our grandfathers was sound. The closest thing most of them had to a detail library was a plastic toilet fixture template, a modular brick scale, and a stainless steel eraser shield. As they moved through the drafting room in their green Josam drafting aprons, they believed that mere observation of existing details and drawn works was not enough. They believed that explanation and step-by-step discussion was required. This belief endured even when their explanation was presented with the stern expectation that you would heed what they said.

If we are to return to a course of excellence in working drawings,

we must apply our grandfather’s model to our electronic environment.

We must print out the detail library and paste it on the wall. We must

take out our red pens and brainstorm the parts and pieces through interactive

discussions. Before the young architects put their hands on the mouse,

they should first know why they have chosen that detail, how they need

to change it to make it work, and how to coordinate it with related components

and systems.

If we are to return to a course of excellence in working drawings,

we must apply our grandfather’s model to our electronic environment.

We must print out the detail library and paste it on the wall. We must

take out our red pens and brainstorm the parts and pieces through interactive

discussions. Before the young architects put their hands on the mouse,

they should first know why they have chosen that detail, how they need

to change it to make it work, and how to coordinate it with related components

and systems.

Our grandfather’s drawings were produced in a time of simpler building systems and less proprietary differentiation of building materials. Nevertheless, our grandfathers arguably produced a better quality working drawing, using a time honored apprenticeship process that we can learn from today. Regardless of the promise of new and improved methods of CAD, such as the building information modeling, the need for architects to understand the requirements for organizing and producing working drawings and applying professional judgment in meeting those requirements will remain. Perhaps the past is as much a part of the future as the future itself. Perhaps, even against the backdrop of today’s computer technology, the primary goal in performing our services should be to produce our grandfather’s working drawings.

And as you consider these nostalgic thoughts about the past, and ponder the future, we’d like to remind you … be careful out there.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

This series will continue next month in AIArchitect with “Drawing the Line.” Find out why the architect’s documents alone are insufficient for construction. If you would like to ask Jim or Grant a risk or project management question or request a specific topic, contact the AIA general counsel’s office. Don’t miss “Focus on Construction Drawings: New Solutions to Old Problems,” a program from the AIA 2005 National Convention and Design Exposition, soon available on AIA eClassroom. Jim Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS Architects in Dallas. He serves on the AIA Documents Committee and the AIA Risk Management Committee. Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, manages project delivery with RTKL Associates in Dallas. He serves on the AIA Practice Management Advisory Group. This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions and illustrations apply to specific situations.

|

||