Summary: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity. These past few years have challenged our profession. We have experienced a surge in work like never before. It has tested our resources, and it has had a catalytic effect on the way we practice and view what we do professionally. We now use electronic tools to deliver our services. The way we work and communicate has changed dramatically for most architects. Our telephone does not have a cord anymore, and the Architect Registration Examination can no longer be taken with a Number 2 pencil. These changes have brought us to the threshold of a new and profoundly different way to work. Alas, BIM! Changes have brought us to the threshold of a new and profoundly different way to work You may recall our past observations in the articles, “Your Grandfather’s Working Drawings” and “The Speed of Life,” where we gazed nostalgically upon “the way it was.” We now find ourselves worn thin by work and winter, and we succumb to the urge to take yet another look both back and forward at the wonder and promise of our profession and the ensuing changes over the years.

Our commentary in “Grandfather” took on mixed reviews, some opining sentimental banality and others grateful for the fond look at past experiences. Responses were divided essentially by age group, of course. We were grateful for all these observations since our core purpose is to stimulate. Accordingly, we believe that there is substance in all experiences, in our losses as well as our gains, so buckle up, and get ready for a look at the architectural practice of our apprenticeship, the vanished treasures, and those from whom we learned. Lessons learned

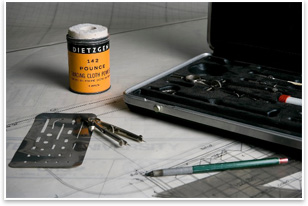

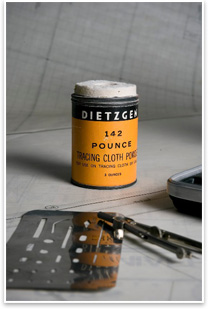

Architecture as a profession has traditionally been steeped in effective and thorough communication. Bricks don’t care much about communication, they just like to be laid straight, true, and plumb. Water doesn’t care much about communication, as long as its “users” understand that it does very much like to run downhill. Without effective communications among each other, architecture is a lost cause. Without effective communications between each of us and the profession we love, there are no effective architects and hence, no meaningful architecture. Life as an architect cannot devolve into a constant race to do things faster and more efficiently. There is a limit beyond which it cannot go. Life as an architect must involve contemplation of the art, loving caresses of the medium, and never-ending introspection about how we can effectively communicate with ourselves and others who interact with us. Without effective communications among each other, architecture is When we were young, we thought that we were different from and could not understand our parents and grandparents. Now we find that we are not understandable or recognizable by our children. The more seasoned among us actually emulate our elders, if we’ll allow ourselves a look inside. The apprentices among us are just as certain as we were of our forebears, that we don’t understand them at all. The future has always been what the future was. That is, except for Rapidograph pens, 1000H Clearprint drafting paper, and that little can of Pounce.

As you put on your coat and gather up your briefcase headed to your next meeting, amble by the digital sender, or stop by an intern’s computer station, and gaze at what is before you. And as you observe, understand that in an instant, it all can and will change. Then head for the door and try to be careful out there.

|

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

To read the full-text PDF version of this article, click here.

This series will continue next month in AIArchitect when the subject will be, “Who’s on First?” We will explore staffing and management challenges in this highly active, but resource-deprived market. If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk- or project-management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them through AIArchitect.

James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal and risk manager with HKS Architects. He serves on the AIA Risk Management Committee and is chair of the Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 14th Edition Task Group.

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, manages project delivery for RTKL Associates. He serves on the AIA Practice Management Advisory Group.

This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions, and illustrations apply to specific situations.

Photos by Blake Marvin.

Best Practices

Best Practices  Substance in all experiences

Substance in all experiences It’s all about communications

It’s all about communications The loss of the treasures of our past sends us a profound message that, if recognized, can strengthen us for the present and the future. Most things will never be as they were, but one undeniable constant remains. Like it or not, change is our future . . . us, all of us.

The loss of the treasures of our past sends us a profound message that, if recognized, can strengthen us for the present and the future. Most things will never be as they were, but one undeniable constant remains. Like it or not, change is our future . . . us, all of us.