11/2005

by

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, and James B. Atkins, FAIA

by

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, and James B. Atkins, FAIA

We must survive this day, we must get about it gentlemen!

—Captain Jack Aubrey

Execution of the architect’s authority falls into three categories: making decisions, giving recommendations (shared responsibility with owners and/or contractors), and leaving the responsibility entirely to others. This article—in two parts—will examine some of the primary areas of the architect’s authority relative to decisions and recommendations. Part One addressed when it is appropriate to act as master and commander and take control, and when it is appropriate to leave decisions to those who hold that contractual responsibility. Now, in Part Two, we will tackle when to act as consultant and only give recommendations. This is an all-important issue of the professional standard of care, which is what defines professional responsibility, as well as how the perception of others can influence required actions.

Shared with the owner

The architect shares a key element of the design process with the owner.

Design phase completion: Although the architect has some authority for

monitoring and maintaining the aesthetic design during construction,

that authority is not absolute and is very limited in earlier phases.

During both the schematic-design and design-development phases of the

architect’s services, the architect is not entitled to proceed

to the next phase until the owner has approved the designs proposed by

the architect. B141-1997, in several locations states:

. . . the Architect shall prepare, for approval by the Owner, . . . documents . . .

And,

Based on the approved . . . (Schematic Design or Design Development) . . . documents

and any adjustments . . . authorized by the Owner in the program,

schedule or construction budget . . .

This language makes it clear that the owner is to play a major role

in deciding the design of the project, albeit normally based upon the

recommendations and proposed designs prepared by the architect.

This language makes it clear that the owner is to play a major role

in deciding the design of the project, albeit normally based upon the

recommendations and proposed designs prepared by the architect.

Shared with the contractor

Submittal schedule: In accordance with A201-1997,

section 3.10.2, the contractor is required to submit a Submittal Schedule

for the architect’s

approval. The contractor is representing that this is the sequence and

timing in which it intends to submit its submittals, but the architect

must determine if that proposed process is consistent with reasonable

operations. For example, if the wood doors, hollow metal frames, and

hardware are not submitted concurrently, you may have to wait until you

have all three to conduct an effective review. With maximum review time

requirements often included in your services agreement, this wait could

cause a failure to meet those requirements, and it could result in a

claim.

Submittal review: Embedded in the process of most modern construction projects is the mistaken belief that only the architect is responsible for submittal review. As we explained in “Drawing the Line,” nothing could be further from the truth. The architect’s role in submittal review is decisively subordinate to the role of the contractor and should commence only after the contractor has completed a thorough review of the submittals. Thus, the architect shares the responsibility and authority for submittal review with the contractor. This shared responsibility is made abundantly clear by A201-1997, Article 3.12.6, which states:

Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples and similar submittals are not contract documents. The purpose of their submittal is to demonstrate for those portions of the work for which submittals are required by the contract documents the way by which the contractor proposes to conform to the information given and the design concept expressed in the contract documents [bold added].

In other words, shop drawings, product data, samples, and similar submittals

are the manifestation of the contractor’s plan for what building

systems and materials it proposes to procure, and how it proposes to

incorporate those systems and materials into the work.

In other words, shop drawings, product data, samples, and similar submittals

are the manifestation of the contractor’s plan for what building

systems and materials it proposes to procure, and how it proposes to

incorporate those systems and materials into the work.

A201-1997, Article 3.12.6 further clarifies the contractor’s responsibility for reviewing and approving submittals:

By approving and submitting Shop Drawings, Product Data, Samples and similar submittals, the Contractor represents that the Contractor has determined and verified materials, field measurements and field construction criteria related thereto, or will do so, and has checked and coordinated the information contained within such submittals with the requirements of the Work and of the Contract Documents [bold added].

As a caution, if you work with a contractor who consistently submits

unmarked and thus clearly unchecked submittals, then you may consider

placing the owner on notice that the contractor does not appear to be

honoring its obligation to review, coordinate, and approve submittals.

Telltale signs are submittals with only the contractor’s approval

stamp and signature and no other marks or comments. This could be true

especially if you are encountering a large number of apparent discrepancies

in the submittals.

As a caution, if you work with a contractor who consistently submits

unmarked and thus clearly unchecked submittals, then you may consider

placing the owner on notice that the contractor does not appear to be

honoring its obligation to review, coordinate, and approve submittals.

Telltale signs are submittals with only the contractor’s approval

stamp and signature and no other marks or comments. This could be true

especially if you are encountering a large number of apparent discrepancies

in the submittals.

Rejection of nonconforming work: An important requirement of the architect during the construction phase is the determination of work conformance to the contract documents and the subsequent rejection of work that does not conform. Likewise, the contractor, whose contract with the owner requires strict conformance to the contract documents, is accordingly required to reject any work that does not conform.

It follows that the contractor has a duty to determine, during its detailed review and coordination of submittals, if conformance is being met and to reject any proposed work that does not conform to the contract documents. An issue apparently misunderstood in many contractor submittals is that the architect may rightfully assume that the contractor’s submittals represent proposed work that the contractor has determined will conform to the design concept expressed in the contract documents.

Shared with the owner and contractor

Project quality: Although the architect

is required in A201-1997 to determine:

. . . in general if the Work is being performed in a manner indicating

that the Work, when fully completed, will be in accordance with the Contract

Documents

in so doing, the architect must determine “in general” if

the quality of the work falls to a level that would prevent it from conforming

to the contract documents. Although the owner may decide to accept a

quality that does not conform to the documents, the owner has the privilege

of accepting what the architect may determine to be “owner-accepted

nonconforming work.”

The contractor, on the other hand, has a duty and guarantees to provide quality work. In A201-1997, Article 3.5, WARRANTY:

The Contractor warrants to the Owner and Architect that materials and equipment furnished under the Contract will be of good quality and new . . . that the Work will be free from defects not inherent in the quality required or permitted, and that the Work will conform to the requirements of the Contract Documents [bold added].

The words “of good quality” are a contracted assurance that

the work will be of a quality that does not contain defects or deficiencies

not inherent in the materials and systems purchased and installed in

the work.

The words “of good quality” are a contracted assurance that

the work will be of a quality that does not contain defects or deficiencies

not inherent in the materials and systems purchased and installed in

the work.

The bottom line is that, although the architect endeavors to guard the owner against defects and deficiencies in the work, the contractor may produce poor quality work that the owner may choose to accept for cost benefit reasons or to expedite the project. If this should happen, the architect should first determine if the work meets the intent of the contract documents and, if not, qualify it in the Certificate of Substantial Completion as “owner-accepted nonconforming work.”

One final caution about changes in the work is necessary. In an effort to move the project along and be a team player, architects sometimes agree to a field modification or a “work around” proposed by a contractor. They agree that the work should proceed accordingly. Caution must be taken that the change, although minor, does not ultimately affect the contract sum or time, for, if it does, the architect will have exceeded or may appear to have exceeded, his or her authority. For this reason, even minor changes should be well-documented, and all such documentation should contain the caveat that “the contractor shall not proceed with this work if it results in a change in contract sum or time unless first approved by the owner.” Both the ASI and the RFI documents contain this provision.

Changes in the Work: The scope of the contractor’s work is expressed

in the contract documents, and A201-1997 states in Article 1.1.1 that

the scope can only be changed with:

Changes in the Work: The scope of the contractor’s work is expressed

in the contract documents, and A201-1997 states in Article 1.1.1 that

the scope can only be changed with:

(1) a written amendment to the Contract signed by both parties, (2) a Change Order, (3) a Construction Change Directive or (4) a written order for a minor change in the Work issued by the Architect.

The architect can approve changes in the work that do not affect the contract sum or time as allowed in article 2.6.5.1:

The Architect may authorize minor changes in the Work not involving an adjustment in Contract Sum or an extension of the Contract Time which are consistent with the intent of the Contract Documents.

This can be accomplished through AIA Document G710-1992, Architect’s Supplemental Instructions. In this case, the architect can change details and design configurations as long as the contract sum and time is not affected. This is somewhat idealistic because of the tendency of contractors these days to claim additional cost and/or time on RFIs and ASIs with most changes.

Generally, when change orders are executed, the owner decides ultimate approval, but the architect indicates approval as well. However, the architect’s approval is to indicate knowledge and acceptance of the change. The architect’s signature does not determine if the change is to be approved, but the architect does have the authority to reject the change by not signing the change order document. Such an action would be taken should the change appeared not to be valid. As a recourse, in AIA Document B141-1997, Article 2.6.5.2 gives the architect the option:

If the Architect determines that requested changes in the Work are not materially different from the requirements of the Contract Documents, the Architect may issue an order for a minor change in the Work or recommend to the Owner that the requested change be denied.

Although the architect cannot approve a change without the owner’s

consent, the architect can prevent the approval of a change by not signing

the change order. When this situation occurs and pressures are brought

to bear, some architects have a tendency to acquiesce and sign the document.

This can lead to problems later if the owner should decide that the change

was caused by an error or omission in the architect’s documents

or if they subsequently come to believe that the change order pricing

was excessive.

Although the architect cannot approve a change without the owner’s

consent, the architect can prevent the approval of a change by not signing

the change order. When this situation occurs and pressures are brought

to bear, some architects have a tendency to acquiesce and sign the document.

This can lead to problems later if the owner should decide that the change

was caused by an error or omission in the architect’s documents

or if they subsequently come to believe that the change order pricing

was excessive.

As a final note, to clarify the architect’s authority in approving changes, the importance of managing scope changes is addressed in the AIA 2004 Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct, wherein it is stated:

Rule 3.103: Members shall not materially alter the scope or objectives of a project without the client's consent.

The architect’s authority notwithstanding, it is worthy of note that the owner also has authority to make changes without the consent or acknowledgement of the architect.

Conclusion

Discipline will count just as much as courage. True discipline goes

to the board!

—Captain Jack Aubrey

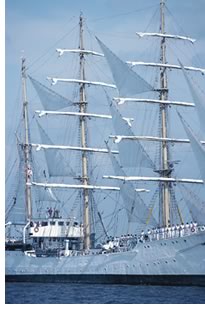

Captain “Lucky” Jack Aubrey was a person of conviction. He knew his rights and his duties to the king, but he knew his limitations as well. He sailed the HMS Surprise successfully and to the benefit of his country by knowing and acting on those parameters. Captain Aubrey wasn’t “Lucky” at all. He was a sailor’s sailor, a master tactician, courageous, and brutally efficient with both cannon and sword.

Within our contracted services we are sometimes master and commander,

but we are also sometimes a consultant who will only advise and recommend.

We will only be able to tell the difference between the two and act appropriately

if we know our documents and our duties.

Within our contracted services we are sometimes master and commander,

but we are also sometimes a consultant who will only advise and recommend.

We will only be able to tell the difference between the two and act appropriately

if we know our documents and our duties.

The activities over which we do have authority carry high risks. Owners depend on us to determine work conformance, certify payments, and determine project completion. Contractors strive to conform to the design concept as they develop their Plan for the Work. They depend on our judicious and timely actions, but we must know our power and our limits of authority. We must be aware of when we are master and commander and when we are merely a consultant. The ability to differentiate between the two, as Captain Aubrey might attest, will influence the success of our efforts.

Meanwhile, as you approach your projects and call your crew to quarters, and as you set sail on your next endeavor, we will kindly remind you to be careful, because the Surprise may be out there.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

To

read “Master and Commander: The Architect’s Authority,” (part

one of this article) go to last week’s AIArchitect. This series will continue next month in AIArchitect, when the subject will be “Lemons to Lemonade— Benefiting from Mistakes.” Find out how to take unfortunate experiences and turn them into meaningful improvements in your practice. If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk or project management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them via the AIA Risk Management office. James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS in Dallas. He serves on the AIA Documents Committee and the AIA Risk Management Committee. Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, manages project delivery for RTKL Associates in Dallas. He serves on the AIA’s Practice Management Advisory Group. This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions and illustrations apply to specific situations. To read the previous Best Practice for Risk Management article,

Zen and the Art of Construction Administration, parts one and two,

go to those issues of AIArchitect:

|

||