11/2005

by

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, and James B. Atkins, FAIA

by

Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, and James B. Atkins, FAIA

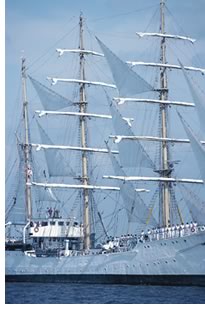

The authority of the architect when providing services can be an issue with diverse viewpoints. Owners may look on the architect’s authority as being very limited or perhaps nonexistent, or they may expect the architect to control all of the design and construction activities. Contractors may struggle with the architect’s “document interpretations” and consider themselves to be responsible for final design configurations, or they may look to the architect to confirm all design interpretations. Architects may struggle with a desire to be the master builder with control and leadership over the entire project delivery process.

Indeed, some architects feel intense ownership of their projects and demand strict adherence to their design requirements. Much like Russell Crowe’s character, Captain “Lucky” Jack Aubrey, in Patrick O’Brian’s, Master and Commander, they seek complete control of project activities, their crew, and all whom they encounter.

The reality is that the architect’s authority is typically determined by two external sources. Certain powers are conveyed by our service contracts, and others are compelled by the standard of care consistent with the practice of architecture. Although our duties can be influenced by owners’ and contractors’ opinions and expectations, the base line of our obligations and authority is typically well established at the onset.

Execution of the architect’s authority falls into three categories: making decisions, giving recommendations (shared responsibility with owners and/or contractors), and leaving the responsibility entirely to others. The architect is typically in command of the outcome on a few occasions related to the former category—when making definitive decisions—yet can only attempt to influence the outcome on the many other occasions when sharing responsibility and giving recommendations. In those instances when the responsibility is entirely up to others, it is probably best to leave well enough alone, because, as any risk manager will tell you, no good deed goes unpunished.

This article—in two parts—will examine some of the primary areas of the architect’s authority relative to decisions and recommendations. It will address when it is appropriate to act as master and commander and take control, when it is appropriate to leave decisions to those who hold that contractual responsibility, and—next week—when to act as consultant and only give recommendations. This is an all-important issue of the professional standard of care, which is what defines professional responsibility, as well as how the perception of others can influence required actions.

The architect’s basis of authority—common authority

The architect’s authority is typically derived from essentially two external sources, the services agreement and the professional standard of care.

It’s leadership they want … strength … find

that within yourself, and you will earn their respect.

It’s leadership they want … strength … find

that within yourself, and you will earn their respect.

Captain Jack Aubrey

A factor governing the level of services that the architect must provide in a contract is the professional standard of care. The standard of care is defined by state law, and varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. A typical formula can be found in The Architect’s Handbook of Professional Practice, 13th edition:

The architect is required to do what a reasonably prudent architect would do in the same community and in the same time frame, given the same or similar facts and circumstances

However, this standard, and sometimes the law, cannot be strictly applied in the judgment of professional performance. A qualified architect, serving as an expert witness, must address the performance of an “accused” practicing architect regarding conformance to the standard of care. Simply stated, an architect typically is required to decide, advise, and/or recommend in a prudent manner consistent with other architects engaged in a similar practice. A definition of the standard of care is being considered for inclusion in the 2007 AIA document revisions. Suggested language currently exists in B511-2001, Guide for Amendments to AIA Owner-Architect Agreements.

The architect’s basis of authority—contracted authority

Quick is the word, and sharp is the action.

Captain Jack Aubrey

Many of the architect’s duties and responsibilities on a project

are established in the Owner-Architect Agreement. They can range from

a brief study to complete basic services required for the design and

construction of a building. In any case, the architect is contracted

to act and provide services to the extent set out in the agreement with

the client.

Many of the architect’s duties and responsibilities on a project

are established in the Owner-Architect Agreement. They can range from

a brief study to complete basic services required for the design and

construction of a building. In any case, the architect is contracted

to act and provide services to the extent set out in the agreement with

the client.

In AIA Document B141-1997, Standard Form of Agreement Between Owner and Architect, the architect’s decision-making powers are noticeably limited. Aside from designing the project and preparing documents to be used for construction, there is no specific mention of what the architect is to do for the owner until Article 2.6, Contract Administration Services, paragraph 2.6.1.3, wherein it states:

The Architect shall be a representative of and shall advise and consult with the Owner during the provision of the Contract Administration Services. The Architect shall have authority to act on behalf of the Owner only to the extent provided in this Agreement unless otherwise modified by written amendment.

The architect’s basis of authority—exclusive authority

Much depends on your accuracy, make your shot count!

Captain Jack Aubrey

Chief among the architect’s exclusive authority is probably aesthetic design. On most projects, the architect is generally looked upon as the party involved who is most qualified to address matters of aesthetic intent. Many owners choose to either delete this from the AIA documents or share the authority with the architect. However, the owner-architect agreements, rather than assign this responsibility in the form of absolute authority up front in the architect’s scope of services, instead authorize the architect to decide aesthetic issues if related to a claim or dispute.

It is addressed in AIA B141-1997, in Article 2.6.1.9, and in AIA B151-1997

in Article 2.6.1.7:

It is addressed in AIA B141-1997, in Article 2.6.1.9, and in AIA B151-1997

in Article 2.6.1.7:

… the Architect’s decisions on matters relating to aesthetic effect shall be final if consistent with the intent expressed in the Contract Documents.

Aesthetic decisions are also specifically addressed in A201-1997, Section 4.2.13, which states:

The Architect’s decisions on matters relating to aesthetic effect will be final if consistent with the intent expressed in the Contract Documents.

The architect’s exclusive authority is further reinforced in Section 4.5 Mediation, where aesthetic decisions are excluded from an appeal for mediation after the architect has ruled.

Regardless of the strict tenor of this language, and aside from the fact that an architect is usually asked to at least give an opinion, in reality, matters of aesthetic intent are rarely decided by the architect as an absolute commander. Even when this authority is conferred, issues such as schedule and cost often cause the architect to arrive at a decision heavily influenced through collaboration with the owner, contractor, and other parties.

Certification of contractor payments. An exclusive duty of the architect that typically survives the owner-architect contract negotiation is the architect’s authority to certify the contractor’s applications for payment. This certification is required for the owner to make payment to the contractor. Although the architect’s certification is based on “the best of the Architect’s knowledge, information, and belief,” it is nevertheless an area of risk that the architect should not take lightly. This certification need not be based on detailed inspections but is necessary to show diligence in gathering the information upon which the opinions certified are based.

Substantial completion. The date or dates of substantial completion are yet another certification that the architect is typically required to provide. Substantial completion is defined in AIA Document G704-2000, Certificate of Substantial Completion:

Substantial Completion is the stage in the progress of the Work when the Work or designated portion is sufficiently complete in accordance with the Contract Documents so that the Owner can occupy or utilize the Work for its intended use.

This certification has significant legal and financial implications because it:

- Determines if the contractor has met its contract obligation

- Triggers payment of the contract balance to the contractor

- Sets the time limit for the contractor to complete or correct the work

- Sets out the responsibilities for security, maintenance, heat, utilities, damage to the work, and insurance

- Initiates the start of warranties for completed work

- Determines the start of legal statutes in most states.

Although the architect has sole authority for determining this date,

pressures are frequently brought to bear by the owner and contractor,

for proprietary reasons, to influence the date. Therefore, the issuance

of this document, like all other architect certifications, should not

be taken lightly, and the information on which it is based should be

diligently gathered and documented.

Although the architect has sole authority for determining this date,

pressures are frequently brought to bear by the owner and contractor,

for proprietary reasons, to influence the date. Therefore, the issuance

of this document, like all other architect certifications, should not

be taken lightly, and the information on which it is based should be

diligently gathered and documented.

As a caution, AIA Document G704-2000 indicates that the warranties for the work indicated on the punch list “will be the date of issuance of the final Certificate for Payment or the date of final payment,” unless otherwise agreed to in writing. To avoid confusion, it is suggested that you line out one of these milestones when you issue the certification. Also, the date of issuance and the date of substantial completion are the same on this form. Since these two activities seldom, if ever, occur on the same day, it is suggested that you add above the architect’s signature line, “The date of Substantial Completion is ______.” The “date of issuance” on the signature line will remain as the issue date.

Final completion. The act of determining the date of final completion is also left to the architect. However, in this instance, no certificate is issued for a very specific reason. If the architect were to certify final completion of the project, this act could be viewed as a representation that the architect had determined that the work was 100 percent complete and in 100 percent conformance with the contract documents, a responsibility that is rightfully left solely to the contractor who put the work in place and warrants the work to be in compliance with the contract documents. To avoid such a representation, the architect administers final completion as stipulated in Article 9.10.1 of AIA document A201-1997:

Upon receipt of written notice that the Work is ready for final inspection and acceptance and upon receipt of a final Application for Payment, the Architect will promptly make such inspection and, when the Architect finds the Work acceptable under the Contract Documents and the Contract fully performed, the Architect will promptly issue a final Certificate for Payment

The final Certificate for Payment essentially becomes the document that establishes the date of the contractor’s completion of the Work. The AIA documents do not include a certificate of final completion, and the architect is cautioned not to issue such a document. If this action is requested by the owner, consult your insurance agent and your legal counsel.

Performance

of the owner and contractor. Both the owner-architect agreements

and the general conditions empower and obligate the architect to render

decisions regarding the performance of the owner and the contractor under

the contract. The architect is required to be impartial when rendering

such decisions, and generally should not be found liable for

these decisions as long as they are rendered in good faith. B141-1997,

Article 2.6.1.7 states:

Performance

of the owner and contractor. Both the owner-architect agreements

and the general conditions empower and obligate the architect to render

decisions regarding the performance of the owner and the contractor under

the contract. The architect is required to be impartial when rendering

such decisions, and generally should not be found liable for

these decisions as long as they are rendered in good faith. B141-1997,

Article 2.6.1.7 states:

The Architect shall interpret and decide matters concerning performance of the Owner and Contractor…

A201-1997, Article 4.2.12, and B141-2007, Article 2.6.1.8 both state:

. . . the Architect shall endeavor to secure faithful performance by both Owner and Contractor, shall not show partiality to either, and shall not be liable for the results of interpretations or decisions so rendered in good faith

Resolution of claims and disputes. The architect’s obligation to provide an initial decision on claims and disputes is addressed in AIA Document A201-1997 in Article 4.4. Due to the breadth of this topic, we will reserve it for another article. But suffice it to say that the architect is authorized to rule on such issues with the initial decision.

The architect’s absence of authority

It would serve no purpose for the men to see this weakness in me, even

this most human of weaknesses.

Captain Jack Aubrey

There are circumstances and practices within the construction process wherein the architect has, or should have, no authority. This occurs when issues involve work or actions totally within the contractual responsibility of other parties. Examples include means and methods of construction, an agreement to accept defective or nonconforming work, or a decision to stop the work.

Means, methods, and safety precautions. Means and methods of construction are the tools that are required of the contractor to execute its unique plan for procuring and placing the work. The architect should not have, and is not contractually granted the authority to decide the means and methods of construction.

AIA Document B141-1997, Article 2.6.5, states:

AIA Document B141-1997, Article 2.6.5, states:

…The Architect shall neither have control over or charge of, nor be responsible for, the construction means, methods, techniques, sequences or procedures, or for safety precautions and programs in connection with the Work, since these are solely the contractor’s rights and responsibilities...

The contractor’s plan and responsibilities for procuring and placing the work is addressed in the AIArchitect September article entitled, “Drawing the Line.”

Construction schedule. The architect is not responsible for preparing or managing the construction schedule, as is stated in A201-1997, Article 3.10:

The Contractor…shall prepare and submit for the Owner’s and Architect’s information Contractor’s construction schedule for the Work.

The architect may review and make use of the information contained in the schedule, but the architect is not responsible for preparing, approving, or confirming use of the schedule. The architect is also not responsible for planning the procurement and placement of the work to accommodate the contractor’s schedule, all of which fall within the Contractor’s Work Plan.

Acceptance of nonconforming work. The architect cannot accept nonconforming work. The requirement that the architect must “endeavor to guard the owner against defects and deficiencies in the work,” by definition prohibits acceptance of work that does not conform. The architect may or may not present recommendations or opinions about nonconforming work, but only the owner has the contracted right to accept nonconforming work.

Stopping the work. Only the contractor and the owner can stop the work process. The architect has no authority to stop the work, and there is no reference to stopping the work in the AIA contracts or general conditions.

Commanding vs. consulting

Run out the guns, run up the colours!

Captain Jack Aubrey

While the architect is typically empowered to make many decisions, these privileges stop far short of placing the architect in overriding command of a project. Captain Aubrey is not alive and well when it comes to practical behavior by the average architect. The architect’s primary “authority,” save for a few specific exceptions, is an intangible one of leadership toward compromise. Even in the few circumstances where the architect is the only party empowered to act, consideration of the opinions and desires of others is often an important and unavoidable priority.

For

the most part, when “decisions” are required, the architect

is not necessarily the “commander” but rather the “consultant.” A

consultant advises and recommends but seldom actually “decides.” An

issue under consideration in the 2007 revision of A201 and B141 is whether

the architect should be empowered to reject work, since it is the owner’s

final decision anyway. Currently, the architect is empowered to reject

nonconforming work in the AIA documents.

For

the most part, when “decisions” are required, the architect

is not necessarily the “commander” but rather the “consultant.” A

consultant advises and recommends but seldom actually “decides.” An

issue under consideration in the 2007 revision of A201 and B141 is whether

the architect should be empowered to reject work, since it is the owner’s

final decision anyway. Currently, the architect is empowered to reject

nonconforming work in the AIA documents.

Owners who do not have expertise in design and construction may enter into a project with expectations of the architects’ performance that unrealistically exceed what an architect actually is or should be empowered to do. It is in this circumstance that it is most important for the architect to know the difference between commanding and consulting. Enlightening the owner of the differences between the two can make a difference between a successful experience and a failure. Helping the owner to make the decisions that they rightfully should make, or providing them with information or advice they may need to arrive at their decisions, is simply good project management.

Copyright 2005 The American Institute of Architects.

All rights reserved. Home Page ![]()

![]()

|

||

This article will continue next week when the subject will be those many areas where the architect shares decision-making responsibilities with either the owner, the contractor, or both. If you would like to ask Jim and Grant a risk or project management question or request them to address a particular topic, contact them via the AIA Risk Management office. James B. Atkins, FAIA, is a principal with HKS in Dallas. He serves on the AIA Documents Committee and the AIA Risk Management Committee. Grant A. Simpson, FAIA, manages project delivery for RTKL Associates in Dallas. He serves on the AIA’s Practice Management Advisory Group. This article is intended for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The reader should consult with legal counsel to determine how laws, suggestions and illustrations apply to specific situations. To read the previous Best Practice for Risk Management article,

Zen and the Art of Risk Management, parts one and two, go to those

issues of AIArchitect:

|

||