Architects Remember the Building that Helped Put a Man on the Moon

Forty years later, Max Urbahn’s contribution to the space race stands tall

By Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

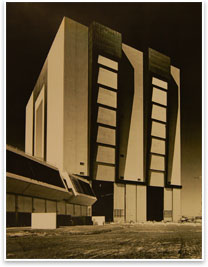

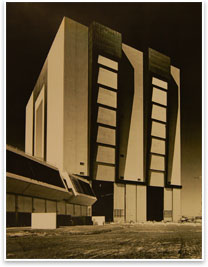

Summary: As tall as a 52-story building and as wide as a city block, the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at the Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island in Florida cuts a stark and lonely profile along the Atlantic Ocean coastline. A brick-like rectilinear mass that’s almost totally devoid of human-scaled features, it’s a hyperbole--a simple, exaggerated sketch of a building.

The Vehicle Assembly Building. Photo courtesy of Alexandre Georges..

And in fact, in its early stages, that’s how it was conceived. The VAB was built to be an assembly facility for the 36-story Saturn rockets that would take man to the moon in 1969. Its architect was the late Max Urbahn, who at the time had just recruited his young architect nephew Richard Bergmann, FAIA, a recent graduate from the University of Illinois—Champagne, to work at his New York firm.

One morning in 1962, Urbahn walked into his nephew’s office and gave him a special assignment. Urbahn was meeting with top NASA officials (including Wernher von Braun, the German rocket scientist that led the development of the Saturn rocket program) to discuss potential schemes for the VAB. He needed Bergman to put together a sketch of his preferred scheme for the building—a back-to-back vertical arrangement. He had four hours to finish it. This was the first Bergmann had ever heard of the project. Urbahn explained his idea for the building and left, clock ticking. On an 8½ by 11 inch sheet of paper, Bergmann went to work. He had the completed sketch blown up to cover an entire conference room wall. As he finished hanging the sketch, Urbahn and von Braun walked in one door and Bergmann slipped out the other.

“Mr. Urbahn didn’t have any idea of what I had done,” Bergmann says. “He acted like it had been there all the time. He was a master of doing things like that.”

Bergmann’s sketch became the building, but as the project moved from the drafting table into the Florida coast it would involve a massive team of architects and engineers that found themselves working on what would be the largest building in the world. Its technical and performance requirements made it a maze of compromises that had to be managed before humankind could set foot on the moon. Urbahn would later tell the Saturday Evening Post that it was the most frustrating building he had ever designed. Philip Moyer, AIA, executive vice president of Urbahn’s firm, said the building’s biggest challenge was “the amount of technical information that you had to absorb in order to put a pencil down on the paper.”

It wasn’t a project made for (or by) free-hand napkin sketches. It was, however, architects’ contribution to the first journey to the moon, 40 years ago this year; the high-water mark of postwar 20th century optimism and faith in country, science, and man.

Buses lining the base of the VAB give a hint at the scale of the building. Photo courtesy of Richard Bergmann.

Once in a lifetime

The VAB was a building that could literally house other buildings, and its dimensions are all superlative and staggering. It was 513 feet wide and 526 feet tall, with an 8-acre footprint. A baseball stadium could be planted on its roof. To allow individual rocket stages to enter the building and leave as an entire 363-foot Saturn rocket, the VAB had four sets of massive doors, the largest of which was 456 feet tall. These doors retracted in 11 sections (four across the building’s base and seven vertically) as layered “leaves.” Opening them entirely took an hour. The buildings at Launch Complex 39 also included a Launch Control Center, where NASA technicians would observe launches from several miles away from the launch pad.

The building’s extreme size and the need to allow equally massive pieces of machinery in and out while performing sensitive, precise technical adjustments on the rockets created untold design constraints and dilemmas.

The VAB was so large it could create its own weather. The architects had to deal with clouds forming in the upper reaches of the building, so they installed special air condition units to move moist air out. True to its location, the building had to contend with hurricane-force winds. It was especially vulnerable to these weather conditions because of its broad massing. To keep the building from blowing away “like a tumbleweed,” as Bergmann says, 41-centimeter piles were driven 150 feet into the earth until they hit bedrock. Twenty to 30 of them were fastened to each column at the base of the building, though it’s concrete foundations. The steel structured building was clad in special aluminum façade panels that could withstand 125 mile per hour winds.

Urbahn and his team were dealing with as many as 100 different building product manufacturers, and had to schedule regular meetings to make sure all the building components fit together. The design couldn’t include any windows because anything large enough to emit a significant amount of natural light would be in danger of shattering when rockets took off only a few miles away. As the design for the VAB progressed, so did the design for the Saturn rocket. VAB architects and engineers had to constantly stay abreast of these changes and how they might affect the design of the assembly building, while still making the facility flexible enough for future NASA rockets. (Indeed, the VAB is still in use today, and is where the Ares rockets NASA hopes may one day go to Mars will be assembled.)

The sheer size of miniature VAB models themselves made them unwieldy

showpieces. Bergmann was tasked with taking a 4-foot-tall model from

New York to Florida, but when his plane landed in Orlando, he couldn’t

rent a truck large enough to transport the model the last 100 miles

to Cape Kennedy. For a few hundred dollars, he ended up commandeering

a donut truck that was making a delivery to the airport coffee shop. “I

ate donuts all the way to Cape Kennedy,” he says.

The size and

complexity of the VAB project required a multidisciplinary approach

that prefigures contemporary design-build and Integrated Project

Delivery models. Beyond their client, the Army Corp of Engineers,

Urbahn’s team included civil, mechanical, foundations, structural,

and electrical engineering firms—all under the banner of URSAM

(Urbahn, Roberts, Seelye, and Moran), an acronym of the first firm

name of each faction. “We created what was probably the largest

integrated A/E office in New York overnight,” Moyer says.

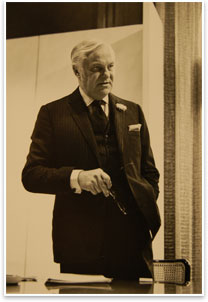

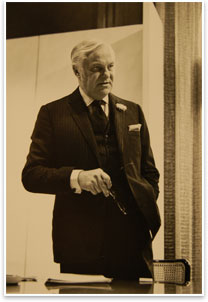

It was Moyer’s job to coordinate the work of all these different disciplines. “I did all the running around,” he says. Urbahn (who was also the 1972 AIA President and who died in 1995) was the “ideas guy.”

President Kennedy’s 1962 declaration that Americans would be on the moon before the end of the decade compressed design and construction timetables and expanded work days. “Failure was not possible,” says Moyer.

“Even before the drawings were done, as soon as we felt comfortable with the analysis of the site, they started driving piles while we were working on the design,” Bergmann says. By the end of 1962, the VAB’s design was finished, and the building was complete in 1966. By then, the URSAM team had completed 18,000 shop detail drawings. One third of them were of the structural steel systems alone. “It was a day and night job,” Bergmann says. “I worked on it as long as I could keep standing. It was the happiest two years I’ve ever had;” and maybe his most unique two years. Much as his uncle had hoped when he brought the young architect to New York, Bergmann was working on a once-in-a-lifetime project. “I’ve never had another project like it,” he says.

Max Urbahn, FAIA, 1972 president of the AIA. Photo courtesy of the AIA Archives.

Moon infrastructure

Bergmann says the VAB project was as much a piece of infrastructure as it was a building. Built to move and construct sky-shattering rockets, it had little to do with human scale and human programs.

“You can’t call it a high rise building,” said John Pendry, a construction superintendent for the VAB. “It’s more like building a bridge straight up.”

Upper stage Saturn rocket sections first entered the VAB into the rear 210-foot low bay, while the taller booster stages entered into the 525-foot high bay. Rocket stages were then inspected and tested. An intricate system of cranes and moveable platforms stacked and assembled the rockets in the high bay. When complete, the space vessel would then leave the VAB thought the high bay doors on a mechanical crawler that traveled on eight tractor treads at one mile per hour towards the launch pad.

“The VAB is not so much a building to house a moon vehicle as a machine to build a moon craft,” said Urbahn in an interview in Astrobiology Magazine.

“It was basically a big engineering exercise,” Bergmann says. “My job was to keep the aesthetics of the thing somewhat intact.” To ensure that the largest building in the world maintained some semblance of architecture, Bergmann looked for way to get any amount of natural light into the building. He settled on a fiberglass sandwich panel system that is strong enough to withstand the blast-off of nearby rockets, but still allowed 50 percent of natural sunlight to penetrate the building. “I couldn’t see it as a cavern,” he says. The design team also used bright colors to code various parts of the VAB interior. Cranes were painted yellow, interior structural elements blue, and moveable platforms red. The high bay doors and their overlapping vertical layers did little to contribute to a sense of normal scale, but their design did offer some geometric variety to the building’s otherwise stark façade. In some cases, Urbahn made design decisions that enhanced and embraced the monumentality of the project, like hiding the low bay building section at the rear of the site, preserving the VAB’s singular presence on the horizon.

Dreaming together

When Moyer first visited the VAB site, he saw nothing but empty coastline and an eagle’s nest where the rocket stages would one day be loaded onto land; a potent patriotic symbol for his project. “It was like going out into the Canaveral wilderness,” he says. But today, the $125 million VAB is only part of the development that sprung up around the Kennedy Space Center. By January of 1965, 15,000 people were working on the Merritt Island complex. Brevard County, Fla., eventually witnessed a tenfold increase in its population. “We did destroy a lot of wilderness, but it was going to be,” Moyer says. “It would never happen today. That’s both unfortunate and fortunate.”

Certainly, attitudes about conservation have grown up for the better since Moyer’s project was put in the ground, but there’s also a twinge of lament to his words. Since the moon launch, the country has had few singular national initiatives that truly take up residence in the unified heart and minds of a broad swath of Americans. Whether through cynicism or splintering cultural tradition, people don’t dream together like they did in July of 1969. Today’s quest to rebuild an ecologically sustainable economy has perhaps the best potential to match the united vision of Urbahn and his contemporaries.

The VAB is a fitting symbol of its age’s post-WWII optimism and bellicosity. It’s completely unselfconscious of its power and presence; a colossal monolith to American ingenuity and pride, governed by technical proficiency and democratic compromise. As such a formative experience for the then-young Bergmann, the VAB made him internalize Louis Sullivan’s “form follows function” Modernist dictum in ways many architects never have the chance to. He says much contemporary architecture “seems arbitrary to me. They have design ideas that go into them that are more interesting than practical.”

There is absolutely nothing arbitrary, or even particular conceptual, about the VAB. Its form doesn’t follow its own function so much as it follows the function of the space vessels it serves. It’s a Final Architecture: the ultimate earthly enclosure before rockets ascend into the infinite spaces beyond. |