Measuring

Sustainability Performance Means Establishing Design Value

Different approaches in Seattle and New York City share a common goal

by Gideon Fink Shapiro

How do you .

. . develop

a dependable database of energy and zero-carbon performance?

Summary: Once

overshadowed by the promise of zero-carbon new buildings, the less

glamorous work of retrofitting existing buildings for increased efficiency

is quickly gaining momentum. Increasingly widespread benchmarking

and disclosure standards are making energy performance an important

new metric across the industry.

NYC Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, Council Speaker

Christine Quinn, and leaders of building trades and environmental

groups introduce the "Greener Greater Buildings Plan" on

April 22.

On April 22, the 39th annual Earth Day, environmental and building

groups joined the mayors of New York and Seattle to introduce new

programs designed to reduce the energy consumption and carbon emissions

of their respective cities’ building stock. The Seattle program relies

on a set of market incentives to encourage owners to measure and

upgrade their building's energy performance. The more stringent New

York legislation would pair market incentives with efficiency requirements

for all commercial, residential, and government buildings. Both programs

use federal stimulus funds to provide low-interest financing for

building upgrades.

These two new programs build on earlier benchmarking laws in California

(2007) and Washington, DC (2008). Austin, Chicago, Berkeley, and

Portland, Ore. are not far behind. Benchmarking is the practice of

evaluating buildings' energy efficiency performance on a standard

scale in order to compare them. Similar to how a car's estimated

fuel economy helps measure its worth, a building's benchmark efficiency

score helps determine its market value to owners, tenants, and prospective

buyers.

The

Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

has been a staunch advocate and consultant for developing benchmarking

policies. Executive Director Cliff Majersik (photoo left) views benchmarking

as a means to re-optimize the market toward green building, and hence

slow climate change. Once owners are made aware of their building's

energy score, he says, "there's low-hanging fruit, investment

opportunities with low risk and high reward that increase performance." Thus

private and public interests begin to dovetail. The Energy Star rating

developed by the Environmental Protection Agency is now the most

common benchmarking system for buildings. The

Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

has been a staunch advocate and consultant for developing benchmarking

policies. Executive Director Cliff Majersik (photoo left) views benchmarking

as a means to re-optimize the market toward green building, and hence

slow climate change. Once owners are made aware of their building's

energy score, he says, "there's low-hanging fruit, investment

opportunities with low risk and high reward that increase performance." Thus

private and public interests begin to dovetail. The Energy Star rating

developed by the Environmental Protection Agency is now the most

common benchmarking system for buildings.

The energy consumed by New York's one million buildings accounts

for a whopping 80 percent of the city's carbon emissions, according

to Rohit Aggarwala, director of Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg's Office

of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability. The agency estimates that

85 percent of the city's buildings in 2030 are already standing today.

In addition to requiring benchmarking for all existing and new city

buildings, the "Greener, Greater Buildings Plan" would

require all renovations to be green renovations, meeting guidelines

of the International Energy Conservation Code regardless of the size

or scope of work. Formerly, many renovations were exempt from the

code if they composed less than half of a building.

The plan would also require existing buildings over 50,000 square

feet to conduct energy audits and efficiency upgrades at least once

every decade. Sensitive to financial as well as environmental interests,

only those retrofits that would pay for themselves within five years

through energy savings would be required, such as insulating pipes,

replacing inefficient lighting, and installing low-flow fixtures.

This systematic, ongoing improvement of existing buildings is the

boldest and most original aspect of the six-point plan, says Aggarwala.

A job training program and $16 million loan fund would help ensure

that the required work can be implemented by skilled technicians

and paid for by owners. If implemented, the plan is predicted to

reduce the city's total carbon footprint by 5 percent—the equivalent

of eliminating all carbon emissions from a city the size of Oakland.

In Seattle, 20 percent of carbon emissions come from residential

and commercial buildings, while around 60 percent comes from transportation.

Beginning next year, Seattle will require commercial buildings larger

than 50,000 square feet and multifamily buildings with more than

20 units to measure and disclose their energy use. Improvements are

optional. "We're trying to do a lot by mandating information

and providing incentives for the upgrades that would follow in hopes

that the market would respond to more information," says Amanda

Eichel, climate protection advisor in the Seattle Office of Sustainability

and Environment.

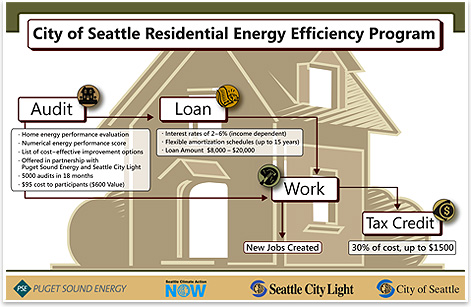

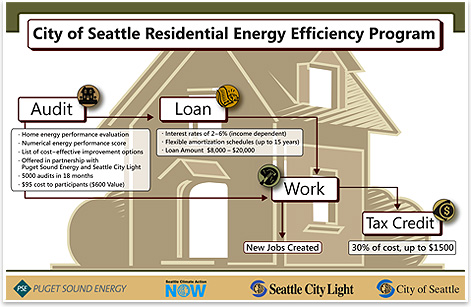

Seattle's pilot program makes it easier for individual homeowners

to improve their home's efficiency. The city convinced the energy

utilities to offer 5,000 home energy audits for $95 instead of the

usual $600, in hopes that the savings by both the company and homeowner

will ultimately exceed the cost of the audit. Improvements following

the audit are not mandatory, but residents can choose to take advantage

of low-interest loans (as low as 2 percent rates for low-income households)

which they don't have to repay until they sell the house. Eichel

says the city will have enough data to assess the residential program

in 2011, and the benchmarking program by 2012.

Poster for the new Seattle energy efficiency program,

in which residents can receive energy audits at a steep discount,

and then borrow money at low interest rates to make efficiency improvements.

Programs for eco-effective renovations and retrofits will help stimulate

the economy, advocates predict. Numerous construction unions have

endorsed the New York plan, in part because of the estimated 19,000

construction jobs it will supposedly create. Whether it will bring

more business to architects remains to be seen, since many of the

building upgrades can be accomplished without an architect's help.

But what is good for the building industry is generally good for

architecture. "You want to be creative" says Paul Katz,

FAIA, a partner at KPF, "The easiest way to stimulate the construction

industry is through renovation. And, of course, renovation and reuse

can be sustainable."

One of the main obstacles the industry must overcome is the conundrum

of split priorities. When the interests of the designer, the building

owner, and the tenant do not align, the result is inefficient buildings,

says Majersik, because "no one thinks they'll get paid for building

efficiently." Another challenge is accurately projecting energy

savings in a volatile market. In New York, passage of the Greener,

Greater Buildings Plan will depend partially on support from building

owners who are wary of promises that upgrades will pay for themselves

within five years. The city council could vote on the plan as early

as late summer or fall.

Policy, practice, and technology take turns leading the charge toward

more sustainable cities. Just a week after New York unveiled its

carbon-reduction plan, the Lightfair International trade show presented

an overwhelming variety of LED bulbs and fixtures, many of which

will find their way into the next generation of renovations. In many

cases, it will be the architects' job to decide how and which new

technology is implemented, and how policy goals are met in practice.

|

The

Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

has been a staunch advocate and consultant for developing benchmarking

policies. Executive Director Cliff Majersik (photoo left) views benchmarking

as a means to re-optimize the market toward green building, and hence

slow climate change. Once owners are made aware of their building's

energy score, he says, "there's low-hanging fruit, investment

opportunities with low risk and high reward that increase performance." Thus

private and public interests begin to dovetail. The Energy Star rating

developed by the Environmental Protection Agency is now the most

common benchmarking system for buildings.

The

Washington, D.C.-based Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

has been a staunch advocate and consultant for developing benchmarking

policies. Executive Director Cliff Majersik (photoo left) views benchmarking

as a means to re-optimize the market toward green building, and hence

slow climate change. Once owners are made aware of their building's

energy score, he says, "there's low-hanging fruit, investment

opportunities with low risk and high reward that increase performance." Thus

private and public interests begin to dovetail. The Energy Star rating

developed by the Environmental Protection Agency is now the most

common benchmarking system for buildings.