The “Placemaking/Sustainability” Connection

by Michael Crosbie, PhD, AIA

Summary: Forging a sense of place should be one of the underlying principles of sustainable design. Why? First, places are sustained and continue to grow by serving the people who live there. The stronger the sense of place, the more people feel invested in the community and strive to preserve it. Second, a community with a strong sense of place encourages residents to experience it at different levels of scale—from the large, overarching umbrella of “this is the place where I live,” to one’s own abode within the larger community. Walkable communities can be experienced on foot, not just observed from inside a car at 40 miles per hour. You don’t really know a place until you’ve spent some time traversing its walkways and paths. Summary: Forging a sense of place should be one of the underlying principles of sustainable design. Why? First, places are sustained and continue to grow by serving the people who live there. The stronger the sense of place, the more people feel invested in the community and strive to preserve it. Second, a community with a strong sense of place encourages residents to experience it at different levels of scale—from the large, overarching umbrella of “this is the place where I live,” to one’s own abode within the larger community. Walkable communities can be experienced on foot, not just observed from inside a car at 40 miles per hour. You don’t really know a place until you’ve spent some time traversing its walkways and paths.

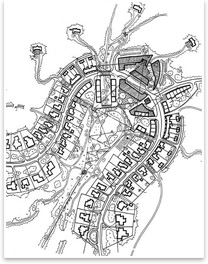

1. Detail of Mado hamlet plan for Phase

2. Selborne hamlet under construction.

3. Serenbe master plan.

Serenbe images courtesy of Phillip Tabb, AIA.

View the slideshow to see all of the images.

Such a notion of sustainability is at the heart of the design of a new community, Serenbe, just outside of Atlanta. Master-planned by architect Phillip Tabb, AIA, who teaches architecture at Texas A&M University, Serenbe has a distinctive layout that achieves sustainable density while keeping nature in close proximity. The community contains about 125,000 acres, but only 20 percent of this land is to be developed as small hamlets (a total of four) that combine living and working. The scheme calls for a total of about 850 homes and several thousand residents. Right now, only one hamlet is completed, Selborne, with approximately 160 residents.

The Serenbe hamlets take their compact form from traditional English villages, Tabb explains—that of a linear spatial form following a road, with a nucleus at the center. You can see the distinctive pattern in Serenbe’s layout, where four hamlets blossom at the apex of roads that appear to meander through the countryside. The serpentine roads might seem picturesque, but they have a sustainable purpose. In each hamlet, the road helps to define and buffer a central green area, usually fed by a stream or containing wetlands, that extends deep into the hamlet. House lots follow the horseshoe-shaped road, with larger lots at the ends of the horseshoe, while at the center the lots are smaller and denser. In a small amount of space the hamlets derive great spatial diversity and density (from one-and-a-half units per acre up to 20 per acre). Another advantage is that the lots back onto green space. “The curvilinear form creates and protects a central portion of the natural landscape,” Tabb points out, open space designed to provide for recreation, organic farming, and scenic beauty. Open land is also used for wastewater and purification systems. Treated effluent water is then used for irrigation and toilets.

The diversity of lot size and density is also reflected in the design and construction of residential, commercial, and civic buildings. Those on larger lots are wood frame and a bit more “rustic” in design. As the density of the hamlet increases, the buildings are closer to the street, and each other, and are masonry construction. Among the sustainable features of the architecture, according to Tabb, are high energy efficiency, improved air quality, water conservation, and resource-efficient building materials. Some of the structures are mixed-use with work-live arrangements—commercial on the ground floor and residential above. Serenbe recently received the Urban Land Institute’s Inaugural Sustainability Award for its approach to land preservation, pedestrian orientation, mixed use, wastewater treatment, and energy conservation. The diversity of lot size and density is also reflected in the design and construction of residential, commercial, and civic buildings. Those on larger lots are wood frame and a bit more “rustic” in design. As the density of the hamlet increases, the buildings are closer to the street, and each other, and are masonry construction. Among the sustainable features of the architecture, according to Tabb, are high energy efficiency, improved air quality, water conservation, and resource-efficient building materials. Some of the structures are mixed-use with work-live arrangements—commercial on the ground floor and residential above. Serenbe recently received the Urban Land Institute’s Inaugural Sustainability Award for its approach to land preservation, pedestrian orientation, mixed use, wastewater treatment, and energy conservation.

A novel aspect of the design is the fact that Tabb has created a metric on 20 different patterns (such as “centering,” “scale,” materiality,” and “ceremonial order”) to gauge the level of community placemaking perceived by the residents. Initial polling and surveys of residents has found that many residents perceive a sense of place. On a 1 to 5 scale, residents give Serenbe an average grade of 4.3 for the perceived presence of “place” and a grade of 3.9 for its expression in built form. Tabb and his colleagues are to be commended for their efforts to actually measure whether their designs are achieving the sense of placemaking that their design strives for. A novel aspect of the design is the fact that Tabb has created a metric on 20 different patterns (such as “centering,” “scale,” materiality,” and “ceremonial order”) to gauge the level of community placemaking perceived by the residents. Initial polling and surveys of residents has found that many residents perceive a sense of place. On a 1 to 5 scale, residents give Serenbe an average grade of 4.3 for the perceived presence of “place” and a grade of 3.9 for its expression in built form. Tabb and his colleagues are to be commended for their efforts to actually measure whether their designs are achieving the sense of placemaking that their design strives for.

Serene is an experiment in planning to make stronger connections between a sense of place and sustainability. So far, the results appear promising.

|