Vancouver Knits Ecology with Urban Fabric

Vancouver Convention Centre West restores habitat and remediates urban blemish

by Heather Livingston

Contributing Editor

Summary: The City of Vancouver, British Columbia, has a longstanding commitment to nurturing an urban core that is elegant, walkable, and sustainable. With the opening of the Vancouver Convention Centre West, the city again reaffirms its intent to provide residents and visitors a world-class, accessible waterfront that also is mindful of ecology. Summary: The City of Vancouver, British Columbia, has a longstanding commitment to nurturing an urban core that is elegant, walkable, and sustainable. With the opening of the Vancouver Convention Centre West, the city again reaffirms its intent to provide residents and visitors a world-class, accessible waterfront that also is mindful of ecology.

In the 1980s, Vancouver set its convention facilities apart with the striking Canada Place, a tensile-fabric roofed structure resembling a ship at full sail in the harbor. Since that time, the convention center has been an iconic and beloved feature on the skyline, but its facilities haven’t been able to keep pace with other cities. For a number of years, LMN Architects in Seattle has worked with the BC Pavilion Corporation to identify an appropriate site for an expanded convention center facility. In the 1980s, Vancouver set its convention facilities apart with the striking Canada Place, a tensile-fabric roofed structure resembling a ship at full sail in the harbor. Since that time, the convention center has been an iconic and beloved feature on the skyline, but its facilities haven’t been able to keep pace with other cities. For a number of years, LMN Architects in Seattle has worked with the BC Pavilion Corporation to identify an appropriate site for an expanded convention center facility.

According to Mark Reddington, FAIA, partner, LMN, the city considered a number of sites throughout the region but ultimately decided that an urban location convenient to Canada Place would serve the city best. Their ultimate choice for the new Vancouver Convention Centre West (VCCW) was the last piece of waterfront property available in the city: a contaminated industrial site that was located within eyeshot and easy walking distance of Canada Place.

A green model A green model

Completed in April, the VCCW is a model of sustainability, expected to earn LEED™ Gold. While LEED projects are becoming the norm rather than the exception, this project is unique in its approach to sustainable building. The first step was, of course, to clean up the existing contamination. As part of that process, the design team collaborated with a broad spectrum of consultants to restore 200 feet of shoreline and 1500 feet of marine habitat. An underwater habitat skirt or artificial reef was designed as part of the VCCW’s foundation and provides a habitat for barnacles, mussels, seaweed, crabs, starfish, and numerous fish species. The five-tiered submerged structure looks like bleachers and creates tidal zones underneath the building that flush daily with the tides.

To preserve potable water, the VCCW employs a blackwater treatment system to process the building’s sewage water for graywater use such as toilet flushing and irrigation for a six-acre green roof. A desalinization plant draws supplemental water from the harbor and processes it for additional graywater uses. To preserve potable water, the VCCW employs a blackwater treatment system to process the building’s sewage water for graywater use such as toilet flushing and irrigation for a six-acre green roof. A desalinization plant draws supplemental water from the harbor and processes it for additional graywater uses.

The green roof, the largest non-industrial living roof in North America, is landscaped with over 400,000 indigenous plants that were specifically selected to attract birds, butterflies, bees, and other beneficial fauna. Reddington says that the stormwater drainage system placed under the green roof was designed so that the moisture content varies throughout the roof to accommodate the desired growing conditions of the plants. “Over time, as plants relocate themselves to their preferred condition, the rooftop will evolve into a naturalistic landscape,” he believes.

An urban model An urban model

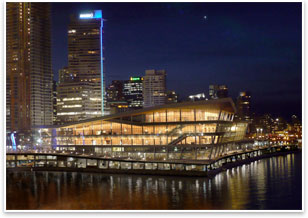

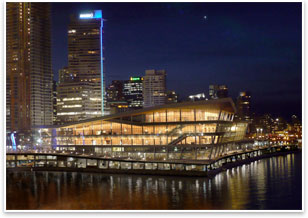

In marked contrast to convention center norm, the VCCW occupies a prime downtown waterfront location and offers extraordinary views of mountains, oceans, and parks. LMN’s design synthesizes a rich public experience through the intersection of the waterfront ecology, local culture, urban context, and program. The building visually links into Vancouver’s harbor greenbelt and Stanley Park at the city’s west end. Over 130,000 square feet of new walking/bike trails criss-cross the site and more than 130,000 square feet of new public plazas, festival spaces, and exterior terraces provide cultural benefits to the city inhabitants and visitors, all visually linked to the waterfront. Finally, the building form creates view corridors from the city’s urban core that extend through to the water, capitalizing on the VCCW’s location at the terminus of two major city streets.

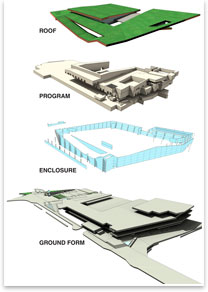

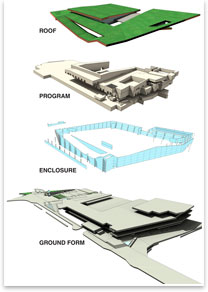

“One thing I think is important [to note] is the approach,” explains Reddington. “It’s such a complex set of relationships and conditions and the building is so large that in some ways it’s not simply a building but an urban design [and ecology] assignment. It has a number of different issues that need to be layered together in order to create an overall solution, so there’s an attitude of integrating all of those in the design approach that was fairly unusual. All of that is technical and rational. “One thing I think is important [to note] is the approach,” explains Reddington. “It’s such a complex set of relationships and conditions and the building is so large that in some ways it’s not simply a building but an urban design [and ecology] assignment. It has a number of different issues that need to be layered together in order to create an overall solution, so there’s an attitude of integrating all of those in the design approach that was fairly unusual. All of that is technical and rational.

“The other side is it still wants to be a really wonderful, inspiring experience for the users at the intuitive emotional level and it is that,” he concludes. “When you go there, it’s completely captivating being on the water and in this dramatic series of spaces that unfold in different directions.”

|

Summary:

Summary: In the 1980s, Vancouver set its convention facilities apart with the striking Canada Place, a tensile-fabric roofed structure resembling a ship at full sail in the harbor. Since that time, the convention center has been an iconic and beloved feature on the skyline, but its facilities haven’t been able to keep pace with other cities. For a number of years, LMN Architects in Seattle has worked with the BC Pavilion Corporation to identify an appropriate site for an expanded convention center facility.

In the 1980s, Vancouver set its convention facilities apart with the striking Canada Place, a tensile-fabric roofed structure resembling a ship at full sail in the harbor. Since that time, the convention center has been an iconic and beloved feature on the skyline, but its facilities haven’t been able to keep pace with other cities. For a number of years, LMN Architects in Seattle has worked with the BC Pavilion Corporation to identify an appropriate site for an expanded convention center facility.  A green model

A green model To preserve potable water, the VCCW employs a blackwater treatment system to process the building’s sewage water for graywater use such as toilet flushing and irrigation for a six-acre green roof. A desalinization plant draws supplemental water from the harbor and processes it for additional graywater uses.

To preserve potable water, the VCCW employs a blackwater treatment system to process the building’s sewage water for graywater use such as toilet flushing and irrigation for a six-acre green roof. A desalinization plant draws supplemental water from the harbor and processes it for additional graywater uses.  An urban model

An urban model “One thing I think is important [to note] is the approach,” explains Reddington. “It’s such a complex set of relationships and conditions and the building is so large that in some ways it’s not simply a building but an urban design [and ecology] assignment. It has a number of different issues that need to be layered together in order to create an overall solution, so there’s an attitude of integrating all of those in the design approach that was fairly unusual. All of that is technical and rational.

“One thing I think is important [to note] is the approach,” explains Reddington. “It’s such a complex set of relationships and conditions and the building is so large that in some ways it’s not simply a building but an urban design [and ecology] assignment. It has a number of different issues that need to be layered together in order to create an overall solution, so there’s an attitude of integrating all of those in the design approach that was fairly unusual. All of that is technical and rational.