| Lifecycle Opportunities for Architects

by Michael Tardif, Assoc. AIA

Contributing Editor

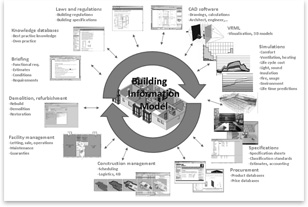

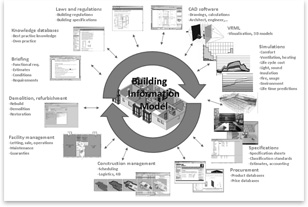

Summary: The life-cycle aspect of building information modeling (BIM) sets it apart from preceding digital design technologies (CAD), which were designed primarily to automate manual processes. The highly structured nature of building information created during design and construction creates business opportunities for maintaining and using building information throughout the building life cycle. Architects are uniquely positioned to capitalize on this opportunity. If they fail to do so, others will.

The volume of building information that has been created thus far is relatively small, and only a fraction of the BIM data produced to date has been passed on to building owners and facility managers, many of whom lack the technology tools and organizational infrastructure to use the data effectively. And while an increasing number of design and construction professionals are showing a willingness to share information with each another, there is a greater reluctance on the part of design professionals to pass building design information onto owners or other third parties for business processes that extend far into the future, for which the information was not originally intended, and over which they will have no control. Statutes of repose for professional liability vary from state to state, but in many cases the “tail” of liability for design professionals extends many years after they have fulfilled their contractual obligations, often far beyond the period of the much lesser general business liability of constructors. As a result, many design professionals reasonably conclude that the risks of releasing digital building information are simply too great. The volume of building information that has been created thus far is relatively small, and only a fraction of the BIM data produced to date has been passed on to building owners and facility managers, many of whom lack the technology tools and organizational infrastructure to use the data effectively. And while an increasing number of design and construction professionals are showing a willingness to share information with each another, there is a greater reluctance on the part of design professionals to pass building design information onto owners or other third parties for business processes that extend far into the future, for which the information was not originally intended, and over which they will have no control. Statutes of repose for professional liability vary from state to state, but in many cases the “tail” of liability for design professionals extends many years after they have fulfilled their contractual obligations, often far beyond the period of the much lesser general business liability of constructors. As a result, many design professionals reasonably conclude that the risks of releasing digital building information are simply too great.

This is one of the dilemmas of the building industry that is seemingly unsolvable, short of modifying state laws nationwide to narrow the scope of professional liability for design professionals. But, as the emerging culture of integrated project delivery demonstrates, conventional, seemingly intractable problems are not likely to be solved with conventional solutions. The important lesson that emerges from the use of BIM in an integrated project delivery environment is that intensive, interpersonal collaboration, in which each participant can observe directly how other members of the project team use building information, is a vital component of information assurance. The lack of similar oversight or involvement hampers the transfer of information at the completion of the design and construction phase. The solution, then, may be to develop similar information oversight mechanisms.

The conundrum: assuring appropriate use

Some way must be found to assure information authors that the information they create will be used appropriately—and at no additional risk to them—once the information is no longer within their realm of responsible control. It is not beyond the realm of possibility for data security technologies to be developed for BIM data, in which information authors would receive the information assurance they most desire: knowledge that the information they created is not being used or modified in a way that will increase their professional liability. Much of the technology already exists and is in widespread commercial use, including automatic notification, data file modification tracking, and change-management logging—think UPS and FedEx.

It would not be difficult for original information authors to monitor continually how the information they created is being used or modified long after their responsible control of that information has ended. BIM audit and analysis tools could be developed and deployed to query and analyze building information models and alert the original authors of any changes that might potentially affect the author’s professional liability. Software tools could be developed, contractual agreements drafted, and business processes implemented that would require the owner to obtain the original author’s consent (or their author’s corporate heirs and assigns) before proceeding with certain types of changes to the model, or indemnify the original author for changes that, in the author’s sole opinion, would unduly expose the author to increased risk.

From the standpoint of our current business culture, such a scenario may seem hopelessly optimistic or naïve. However, another attribute of BIM and integrated project delivery is a shift from a project-to-project business paradigm and toward long-term business relationships with valued and trusted partners. In such an environment, the “lifecycle information assurance” scenario described above becomes far more plausible.

Building information stewardship

It is likely, also, that a new building industry profession or service—building information stewardship—will emerge to meet market demand to sustain building information over the life of a building. In addition to the many people who create or handle building information throughout the life of a building, there are many potential customers for accurate, up-to-date building information that could be extracted from building information models, including emergency responders, insurers, real property portfolio (investment) managers, real estate brokers, and prospective purchasers (future owners) of buildings. Accurate, up-to-date building information will become a tangible asset in its own right that will add value to the real property asset. It is not much of a leap to contemplate that a business opportunity will emerge for “building information assurance agents” who will not only maintain building information models, but will also certify—for a price—that the information they manage and convey to third parties accurately reflect real-world conditions. As the original authors of building information, this is a natural role for architects to assume.

|

The volume of building information that has been created thus far is relatively small, and only a fraction of the BIM data produced to date has been passed on to building owners and facility managers, many of whom lack the technology tools and organizational infrastructure to use the data effectively. And while an increasing number of design and construction professionals are showing a willingness to share information with each another, there is a greater reluctance on the part of design professionals to pass building design information onto owners or other third parties for business processes that extend far into the future, for which the information was not originally intended, and over which they will have no control. Statutes of repose for professional liability vary from state to state, but in many cases the “tail” of liability for design professionals extends many years after they have fulfilled their contractual obligations, often far beyond the period of the much lesser general business liability of constructors. As a result, many design professionals reasonably conclude that the risks of releasing digital building information are simply too great.

The volume of building information that has been created thus far is relatively small, and only a fraction of the BIM data produced to date has been passed on to building owners and facility managers, many of whom lack the technology tools and organizational infrastructure to use the data effectively. And while an increasing number of design and construction professionals are showing a willingness to share information with each another, there is a greater reluctance on the part of design professionals to pass building design information onto owners or other third parties for business processes that extend far into the future, for which the information was not originally intended, and over which they will have no control. Statutes of repose for professional liability vary from state to state, but in many cases the “tail” of liability for design professionals extends many years after they have fulfilled their contractual obligations, often far beyond the period of the much lesser general business liability of constructors. As a result, many design professionals reasonably conclude that the risks of releasing digital building information are simply too great.