A Bridge Can’t Go Too Far

D.C.’s New Wilson Bridge Wins 2008 Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

How do you … factor in the environment when building a new bridge?

Summary: The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) recently honored the D.C. Traffic Improvement Project for its design and engineering of the new Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge in metropolitan Washington, D.C. ASCE’s 2008 Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement (OCEA) Award recognized the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge project for sustainable design programs that protected the environment during construction through soil and underwater vegetation preservation and water and air quality monitoring. The award also honors the project’s programs that will continue to provide green restoration to the surroundings. The project’s ongoing $50 million “green program” of environmental mitigation initiatives will create and restore parks, wetlands, fish passageways, streams, forests, and habitats—all near the bridge and for miles in every direction. The Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge project was selected by ASCE from among 50 entries. Summary: The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) recently honored the D.C. Traffic Improvement Project for its design and engineering of the new Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge in metropolitan Washington, D.C. ASCE’s 2008 Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement (OCEA) Award recognized the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge project for sustainable design programs that protected the environment during construction through soil and underwater vegetation preservation and water and air quality monitoring. The award also honors the project’s programs that will continue to provide green restoration to the surroundings. The project’s ongoing $50 million “green program” of environmental mitigation initiatives will create and restore parks, wetlands, fish passageways, streams, forests, and habitats—all near the bridge and for miles in every direction. The Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge project was selected by ASCE from among 50 entries.

The D.C. Traffic Improvement Project team for the new Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge is the Federal Highway Administration, Maryland State Highway Administration, Virginia Department of Transportation, and the District of Columbia Department of Transportation.

Highly visible project bridges traffic, political, and environmental gaps Highly visible project bridges traffic, political, and environmental gaps

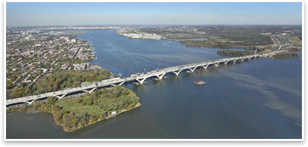

The new Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge—a $2.5 billion project—crosses the Potomac River and connects Virginia and Maryland along Washington, D.C.’s Capital Beltway and Interstate 95. The new bridge replaces the original span built in 1961, which had six lanes, a draw span, and was 5,900 feet long. The new bridge has two spans, with six-lanes on each span—three in each direction. There will also be a drawbridge, with the addition of a separate pedestrian/bicycle trail on the north side. The six-lane outer span opened in mid-2006, and the inner span opened this month.

“It has a combination of technical, political, environmental, and traffic issues that deal with Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.,” explains Bill Marcuson, 2007 ASCE president and member of the OCEA jury composed of engineers and journalists. “Many bridges deal with two states, but seldom do you have three political entities, and seldom do you have the visibility of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge. My guess is half the time people flying in and out of National Airport go right over it, including the president, senators, and Congress members. They did this project right under Congress’s eye. When you look down, it's architecturally pleasing.”

Marcuson adds that the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge carries much of the traffic from Boston, Philadelphia, and New York traveling south. “Think about the number of people. It’s part of Interstate 95, a major north-south artery. The project also finished ahead of schedule and on budget. It was the whole ball of wax—that was what set it apart from the other entries.”

Preserving soil, underwater vegetation; air, water measures

A large consideration for the D.C. Traffic Improvement Project team was its “green program” for both maintaining the environment during construction and creating and restoring the land impacted by the Potomac River crossing. From the new bridge, the green program extends more than 50 miles to the south, 30 miles to the west, and 20 miles to both the north and east.

The design by the D.C. Traffic Improvement Project of the new bridge called for an arch span similar to other bridges in the nation's capital. Soil conditions at the site, however, prevented a heavy arch construction. Instead, the new bridge features precast, cantilevered V-piers that simulate arches, but wouldn’t thrust into the river’s soil, as would conventional arches. In addition, during construction, the old Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge served as a trestle to build the new span’s inner crossing in order to save six acres of dredging and preserve underwater vegetation. “They built the new bridge but continued to operate the old bridge to keep traffic flowing,” adds Marcuson.

To protect fish during pile driving, the project team came up with an innovative solution, Marcuson points out. “They went to extraordinary measures to make sure the fish were not impacted. They created air bubbles around the piles so the impact of the pile driver didn’t create shock waves and kill fish. Air is compressible, water is not. If you have nothing but water when you hit that pile, the energy is transmitted to the fish, and as a result, they are killed. But with the air bubbles, the shock of the pile driver was transmitted and the compressible air took the shock. The fish were in good shape.”

In addition, the project team monitored water quality from six stations, conducted air emissions monitoring, and constructed turbidity barriers to restrict silt and sediment runoff.

Long-range environmental impact

The project includes extensive environmental mitigation initiatives that are in the works for Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. The initiatives include 130 acres of wetland preservation, park land improvements, river grass plantations to serve as fish habitats, 130 acres of reforestation involving planting and preserving woodlands, stream restoration, and habitat preservation for various species. Also, an 84-acre bald eagle habitat has already been established in Prince George’s County, Md., just north of the bridge.

On the Virginia waterfront in Arlington County near the bridge, 2.2 acres of wetlands were created, just to the west of Ronald Reagan National Airport, while a second project site 20 miles south in Woodbridge, Va., restored a 3.5-acre dumpsite into wetlands. An abandoned landfill along the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., meanwhile, is scheduled to be replaced with more than 23 acres of tidal wetlands.

“There were right-of-way, geometry, and intersection issues on both abutments,” explains Marcuson. “On both the Virginia and Maryland sides these cloverleaves—the way you get on and off the bridge—involved traffic flow issues. Much of these cloverleaves took up the wetlands, so they decided to create wetlands in other places a little further away. In terms of environmental impact, we’ve had zero.”

The project also involves fish passage restoration and fish restocking. The fish passage restoration restored 26 miles of fish spawning habitat by removing or modifying 23 manmade barriers to fish passage in five major streams. The intent is to allow fish to return to spawning areas, such as Rock Creek in Washington and the surrounding Anacostia River watershed. The plan also uses a flow constrictor/step pool structure that mimics natural stream channels. For the fish restocking, 6.1 million fish have been released, with up to 9 million to be released in the next few years. The project also includes 22 acres of restoration of submerged vegetation with the planting of thousands of sprigs of grass in several locations near the mouth of the Potomac River in both Maryland and Virginia waters. The vegetation serves as both food and habitat for fish and waterfowl, and as a water purifier.

Says Marcuson, “The Wilson Bridge is a model for architecture, engineering, sustainability, teamwork, negotiations, and getting it done when you have a lot of people involved.”

|