| New Nationals Park Opens in Washington, D.C.

by Russell Boniface

Associate Editor

How do you . . . design a LEED-certified Major League Baseball ballpark on a set budget and tight construction schedule? How do you . . . design a LEED-certified Major League Baseball ballpark on a set budget and tight construction schedule?

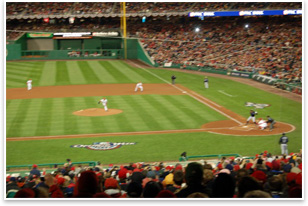

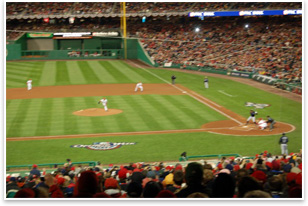

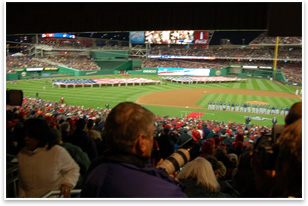

Summary: An energetic crowd of more than 40,000 helped inaugurate the new Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., on March 30. The ballpark, a collaboration of Kansas City-based HOK Sport and architect-of-record D.C.-based Devrouax + Purnell Architects and Planners PC, recently was awarded LEED® Silver certification, the first major league ballpark to be certified by the U.S. Green Building Council. AIA President Marshall Purnell, FAIA, design principal at Devrouax + Purnell, led the way in working with the city and giving the ballpark a design unique to Washington, D.C., while HOK Sport plied their experience to make the facility a top-drawer baseball experience.

AIArchitect was at the ball game opening day to talk with HOK Sport architects Joseph Spear, AIA, principal, and Jim Chibnall, AIA, senior designer. President George W. Bush threw out the first ball, ushering in a new baseball tradition in the nation’s capital—and welcoming baseball and architecture fans to a marvelous ballpark.

To make the ballpark a contextual success, the two architecture firms worked closely with the D.C. Sports & Entertainment Commission (DCSEC), the Council of the District of Columbia, former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, and the Anacostia Watershed Restoration Committee. Clark Construction Group LLC of Bethesda, Md., Hunt Construction Group of Indianapolis, and Smoot Construction of Washington formed a joint venture and completed the ballpark on a tight schedule of 23 months. The $611 million budget, equally tight, was funded by public bonds. To make the ballpark a contextual success, the two architecture firms worked closely with the D.C. Sports & Entertainment Commission (DCSEC), the Council of the District of Columbia, former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, and the Anacostia Watershed Restoration Committee. Clark Construction Group LLC of Bethesda, Md., Hunt Construction Group of Indianapolis, and Smoot Construction of Washington formed a joint venture and completed the ballpark on a tight schedule of 23 months. The $611 million budget, equally tight, was funded by public bonds.

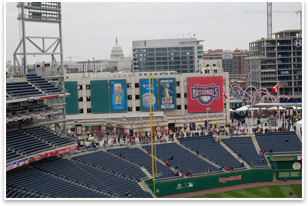

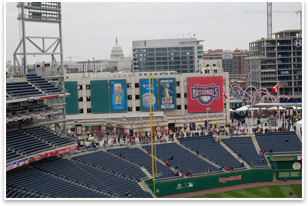

On a 20-acre site just off of the Anacostia River in southeast Washington—a half-hour walk from the U.S. Capitol—the glass and concrete ballpark harmonizes with the limestone context of the city’s federal and monumental architecture. It also serves as the centerpiece of a mixed-use waterfront development plan currently under way.

Collaboration between two experienced firms Collaboration between two experienced firms

“The city picked the location as a result of finding a place that needed economic stimulation,” Purnell explains. “We were in a joint venture with HOK Sport. Our firm focused on what could make it uniquely Washington, and HOK Sport focused on making it a first-class ballpark by the standards of Major League Baseball. We put our strengths together and made allowances in the budget for LEED.”

Collaboration was key. “We pooled the staff in one office,” says Spear. “It was a collaborative arrangement that worked well,” adds Chibnall. “Marshall’s firm was just a slam-dunk. It was a wonderful relationship. Devrouax + Purnell were wonderful to work with. They had an understanding of the city and of the processes needed to get the project through, such as knowledge of permitting, design review, and planning. They assisted us tremendously.”

Take me out to the ball game Take me out to the ball game

The asymmetrical ballpark, sited at the confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac rivers, reflects its surrounding diagonal street geometry, which evokes the District’s street plan laid out by Pierre L’Enfant. The ballpark’s monumental façade along the third base/left field side on South Capitol Street has a hard edge pointing toward the U.S. Capitol and, at the ballpark’s south end, a dramatic triangular hard edge pointing out towards the river.

That façade, along with the row of housing across the broad street, creates a forced perspective, with the distant Capitol Dome highlighted at the vanishing point, “so you can’t miss the Capitol,” notes Spear. As Purnell says: “What the façade looks like on South Capitol was not a baseball issue—it was a Washington issue.” The monumental façade also serves as a gateway for cars entering the city via the Douglas Bridge. Ground-level openings offer street-level glimpses into the ballpark.

The ballpark’s seating capacity is approximately 42,000. Decks—including bleachers—are arranged in neighborhoods, each with its own identity and views. The seating bowl comprises blue seats, with a section of red bleacher seats beyond the outfield fence. There is a red press box on the upper two levels. The right side of the upper bowl features a split that drops 25 feet to open up a view of the river. Says Purnell, “The upper deck stands are 25 feet lower at that point because we have suites that go from infield dirt to infield dirt. There are also suites on the third-base side from the infield dirt out to the outfield; those are the party suites rented game-by-game by corporations.” The ballpark’s seating capacity is approximately 42,000. Decks—including bleachers—are arranged in neighborhoods, each with its own identity and views. The seating bowl comprises blue seats, with a section of red bleacher seats beyond the outfield fence. There is a red press box on the upper two levels. The right side of the upper bowl features a split that drops 25 feet to open up a view of the river. Says Purnell, “The upper deck stands are 25 feet lower at that point because we have suites that go from infield dirt to infield dirt. There are also suites on the third-base side from the infield dirt out to the outfield; those are the party suites rented game-by-game by corporations.”

Pedestrian ramps and concourse plazas provide framed views toward the Anacostia waterfront, Potomac River, Washington Monument, the U.S. Capitol, and District residences. There is a framed view of the Capitol down the left field line that can be seen from certain vantage points in the seating bowl and press box. Spear notes that the architectural elements at National Park help wayfinding. “The old stadiums like Shea Stadium and RFK [in D.C.] are redundant and repetitive. You get on a ramp and have no idea where you are when you get off. Am I close to home plate? Am I close to third base? At Nationals Park, for example, you see the gap in the concourse and seating bowl and know you are close to first base.”

Designed with the fans in mind Designed with the fans in mind

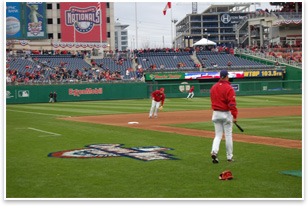

The ballpark’s wide concourses offer fans unobstructed views toward the games, plenty of vendors, and breezeways that will help quell the D.C. humidity. “You can still watch the game,” Spear comments on the unobstructed concourses. “Baseball is a relaxed pace where fans socialize. We wanted fans to be able to get up, have time to stretch, and feel like they have enough room to walk around. Plus, during a rain delay, we want people to come over to the open but covered concession area. If you don’t give them some place to go during the rain, they’ll go home.”

Beyond the asymmetrical fence are a large, high-definition scoreboard, picnic deck, kids’ areas, cherry trees, and a concession area with a highly visible sedum-planted green roof for heat absorption. An open pavilion beyond the outfield wall leads to the grand entry gate directly beyond centerfield. “Seventy-five to 80 percent of the people the first year will use that entrance every day,” says Spear. “We over-designed the other entrances because we expect 20 percent, by year five, to use the other entrances when there is more parking. That is the home plate entrance. There is also a grand Potomac-side stair that people can take down to the river after the game.”

Getting it done Getting it done

Planning for the ballpark began before the Lerner Group came on as the owner. “Initially, Major League Baseball was working with the city to select a site,” says Chibnall. “They looked at 19 sites in the general region. It was Mayor Williams who determined this was the best spot for a baseball park. At the time, this part of D.C. was the last bastion of available land in the district, and he saw a vision here. We worked diligently to accomplish that, and, for the next few years, there will be continuous construction and development here.“

“The process ended with the construction team clearing the site and building the ballpark in 23 months,” says Spear. Says Chibnall: “I think at the end of the day it’s a beautiful ballpark. It’s what D.C. needs, and what they deserve.”

Purnell points out that Nationals Park is a public-oriented project. “There is so much going on now around that ballpark as a result of the city making that investment,” he says.

Spear and Chibnall commend the owners, the Lerner family, for adding to the design. “The Lerners were able to do things, which they paid for, to improve the experience for the fans, such as increasing the size of the scoreboard and picnic deck and adding cherry trees beyond the outfield,” notes Spear. “It was a good relationship.” Says Chibnall, “We had to use historic precedent and look at what we did at other ballparks, but it was nice to have an ownership group making the building their own and incorporating their ideas into the design.” Spear and Chibnall commend the owners, the Lerner family, for adding to the design. “The Lerners were able to do things, which they paid for, to improve the experience for the fans, such as increasing the size of the scoreboard and picnic deck and adding cherry trees beyond the outfield,” notes Spear. “It was a good relationship.” Says Chibnall, “We had to use historic precedent and look at what we did at other ballparks, but it was nice to have an ownership group making the building their own and incorporating their ideas into the design.”

The first LEED ball park

“It was important to the Sports and Entertainment Commission and Mayor Williams to have the ballpark LEED certified,” explains Chibnall. Blade-like sunscreens sit atop the structure—just one of many elements that contribute to the building’s sustainability. Another is the water infiltration system to treat runoff separately from gray water.

Other elements contributing to LEED certification are:

- An energy-efficient light system, including reflectors that minimize off-field spill light and increase on-field light, which is expected to save $444,000 in energy costs over 25 years

- Removal of contaminated soil from the site

- Light rooftop colors along South Capitol Street to reflect heat

- More than 20 percent of construction materials being recycled

- Efficient, air-cooled chillers are expected to save 6 million gallons of water annually

- Recycling bins for collection of used metal, glass, paper, and cardboard

- Recycled paper products and four on-site recycling compactors

- Low-flow restroom faucets and dual-flush toilets, expected to save 3.6 million gallons of water annually

- Use of sustainable cleaning products and adhesives.

Spear says it’s a great feeling to have a ballpark design come to fruition. “It’s pretty cool. You get used to seeing it as a construction site, but when it opens and thousands of people come in, it’s like a party—really great. It rocks.” While he admits he planned to relax and enjoy the first night, he admitted that architecture would still be on his mind during the game. “I will spend the better part of the game watching to see how people are using the building.” Spear says it’s a great feeling to have a ballpark design come to fruition. “It’s pretty cool. You get used to seeing it as a construction site, but when it opens and thousands of people come in, it’s like a party—really great. It rocks.” While he admits he planned to relax and enjoy the first night, he admitted that architecture would still be on his mind during the game. “I will spend the better part of the game watching to see how people are using the building.”

|

How do you . . .

How do you . . . To make the ballpark a contextual success, the two architecture firms worked closely with the D.C. Sports & Entertainment Commission (DCSEC), the Council of the District of Columbia, former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, and the Anacostia Watershed Restoration Committee. Clark Construction Group LLC of Bethesda, Md., Hunt Construction Group of Indianapolis, and Smoot Construction of Washington formed a joint venture and completed the ballpark on a tight schedule of 23 months. The $611 million budget, equally tight, was funded by public bonds.

To make the ballpark a contextual success, the two architecture firms worked closely with the D.C. Sports & Entertainment Commission (DCSEC), the Council of the District of Columbia, former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, and the Anacostia Watershed Restoration Committee. Clark Construction Group LLC of Bethesda, Md., Hunt Construction Group of Indianapolis, and Smoot Construction of Washington formed a joint venture and completed the ballpark on a tight schedule of 23 months. The $611 million budget, equally tight, was funded by public bonds. Collaboration between two experienced firms

Collaboration between two experienced firms Take me out to the ball game

Take me out to the ball game The ballpark’s seating capacity is approximately 42,000. Decks—including bleachers—are arranged in neighborhoods, each with its own identity and views. The seating bowl comprises blue seats, with a section of red bleacher seats beyond the outfield fence. There is a red press box on the upper two levels. The right side of the upper bowl features a split that drops 25 feet to open up a view of the river. Says Purnell, “The upper deck stands are 25 feet lower at that point because we have suites that go from infield dirt to infield dirt. There are also suites on the third-base side from the infield dirt out to the outfield; those are the party suites rented game-by-game by corporations.”

The ballpark’s seating capacity is approximately 42,000. Decks—including bleachers—are arranged in neighborhoods, each with its own identity and views. The seating bowl comprises blue seats, with a section of red bleacher seats beyond the outfield fence. There is a red press box on the upper two levels. The right side of the upper bowl features a split that drops 25 feet to open up a view of the river. Says Purnell, “The upper deck stands are 25 feet lower at that point because we have suites that go from infield dirt to infield dirt. There are also suites on the third-base side from the infield dirt out to the outfield; those are the party suites rented game-by-game by corporations.” Designed with the fans in mind

Designed with the fans in mind Getting it done

Getting it done