LAPD’s Valley Bomb Squad and Training Facility Opens by Russell Boniface

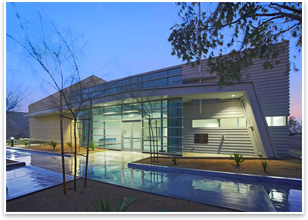

Summary: WWCOT Architects designed a new $7 million Valley Bomb Squad and Training Facility for the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) campus in Granada Hills, Calif. The 9,200-square-foot facility, located north of downtown Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley, officially opened in January. LAPD officers will use the facility to train on domestic terrorism response and the handling of explosives and hazardous materials. The facility, funded through a $600 million bond approved by voters in 2002 to renovate and construct public safety facilities, allows for future growth and technologies in LAPD emergency response.

Andrea Cohen Gehring, FAIA, design partner, WWCOT Architects, says that since 9/11, the LAPD hasn’t had proper facilities for bomb scares, bioterrorism, and environmental threats. “They developed an amazing bomb squad group, but were actually operating out of a temporary trailer,” says Gehring. WWCOT worked with the Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering to develop the two new training facilities. “These facilities are often a utilitarian warehouse, and your first impulse on this type of project is that the building doesn’t have to be a jewel,” Gehring says. “But both the City of Los Angeles and the LAPD had a lot of pride in this project. And for us, a building like this should be a jewel. It will instill pride in the police officers who walk in and out of its doors; who are risking their lives for the rest of us. Why not thank them and celebrate their pride and talent?”

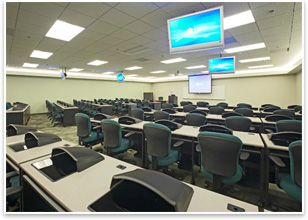

Gehring does, however, reveal that the L-shaped building defines a private courtyard where officers train to dismantle bombs using robots. “They needed a certain amount of outdoor space for a variety of training and exercises. The courtyard is enclosed so anyone with binoculars can’t see what the Bomb Squad is doing and how it’s doing it.” She adds that inside there are offices, labs, conference and training rooms, a lobby, hi-tech and audio visual training, a bay for access to vehicles, and a support structure for the bomb-sniffing dogs.

An example Gehring gives is putting additional outlets in the electrical system to anticipate for future expansion. “The user may not change the carpet every five years,” she points out. “But the building needs to be flexible to take change over time for the things that the user might need to happen. These buildings also need to be designed well, constructed in an easy manner because it’s usually a low-bid scenario, and maintenance free.” |

||

Copyright 2008 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

home

news headlines

practice

business

design

recent related

› Harley Ellis Devereaux, HERA Design Nation’s Largest Crime Lab

› National Law Enforcement Museum to Grace Nation’s Capital

WWCOT team members

• Partner-in-charge: Adrian O. Cohen, FAIA, LEED-AP

• Design partner: Andrea Cohen Gehring, FAIA, LEED-AP

• Forensics partner/Project Manager/QA-QC: Dean Vlahos, AIA, LEED-AP

• Interiors partner: Ben Levin, AIA, LEED-AP

• Project architect: Merritt Evan Raff, AIA

• Interior designer: Janet Rhee, LEED-AP

• Senior technical manager: Michael Ellars, AIA, LEED-AP.

Visit the AIA Academy of Architecture for Justice online.