matri.ARCH.itect: Achieving Balance for Women in Architecture matri.ARCH.itect: Achieving Balance for Women in Architecture

Summary: In mid-2006, I accepted an invitation to participate in a panel discussion at the 2007 AIA National Convention & Expo in San Antonio. Supported by both the Young Architect’s Forum and the Practice Management Knowledge Community, the session was aptly and creatively entitled “matri.ARCH.itect” and addressed issues that women face as they traverse the profession of architecture. It was a pretty good fit, as I am a licensed architect in my mid-40s with my own relatively new firm, a young child, and a very supportive husband of 14 years. But while the coordinator of the session, Kristine Royal, AIA, and its moderator, Emily Grandstaff-Rice, AIA, were organizing the session details and attempting to wrangle the three panelists, I was wondering how I was going to tell them that I would be 8½ months pregnant when the May 6 event rolled around. I considered finding a replacement panelist, but decided instead to use my “condition” to help illustrate my commitment to the topic. If necessary, I could always participate via video-conference, right? Meanwhile, I booked a hotel room close to the convention hall and convinced my husband to accompany me—just in case. Can we have it all? Recommendation #1: Employers and employees alike must recognize that the definition of success varies among individuals, and not necessarily along gender lines. That stated, statistics do illustrate some important parts of the story and compel us to ask several key questions. We know that the number of women in architecture has increased substantially over the past 30 years. (I must also note that although this article is focused on female architects, there is no intent to minimize the importance of addressing challenges of minorities or other underrepresented groups, as this is worthy of its own separate focus.) By tracking the percentages of women in architecture degree programs, intern development programs, professional organizations, upper management and leadership positions, firm ownership, professorships, and other worthwhile activities and measures, we will continue to see incremental advances. The danger is to claim victory through these and other statistical generalizations. For example, according to NAAB, 40-50 percent of the graduates of architecture schools across the country currently are female, yet it is estimated that roughly 20 percent of registered architects in the U.S. are women. According to the AIA, just over 13 percent of its current members are women. So, where are the female architecture graduates and what are they doing? Why are they leaving and what can be done to keep them in architecture? Not surprisingly, there’s no easy answer. One idea is to look to the other gender. Why are male students following through with their careers in architecture? What interests them and keeps them in it? Don’t men seek balance as well? Perhaps, but the AIA’s summary of the 2005 Demographic Diversity Audit notes that female respondents rated "personal/family circumstances" and "inflexible hours" as their primary reasons for not practicing architecture nearly three times as often as male respondents. Recommendation #2: Employers must know and see that employees are treated fairly, focusing on value and performance rather than on gender. This fairness must permeate the firm culture and be evident in staffing/assignments, mentorships, development, advancement, benefits, etc. This will be a solid step towards keeping women in the profession. To complicate the issue, human attributes are not always so clearly gender-specific. For example I cannot cook, and my dear husband has no interest in sports. I happen to have skill and interest in finance, he is patient, artistic, and (luckily for me) loves to cook. When our first child was born, we both took three months of leave from our jobs; the only difference was that my employers were not surprised, while his employers were quite surprised. Comments from one matri.ARCH.itect attendee’s evaluation form stated: “At first I thought I might walk out, but I found that the subject matter really affects all genders and the content kept me attentive and engaged, even though I am a man.” During our Q&A, one male attendee stood to pose a question to the panel, but got so choked up that he could barely speak the words. His wife had Alzheimer’s disease and his life’s regret is that he didn’t spend enough time with her. No easy answer indeed … My intent is not to argue that there are no differences between genders, but that those differences should be celebrated, on an individual scale, as opposed to looking for one-size-that-fits-all-women and another size-that-fits-all-men. Individuals have unique talents, needs, and interests, and firms must find ways to accommodate them, regardless of gender. Recommendation #3: Architecture firm leadership should support their staff as individuals who pursue life balance, however they individually define it. As an employee at a large architecture firm in the 1990s, I watched female peers more talented than I who happily (sometimes desperately) returned from maternity leave. Many of them sought flexible hours or part-time positions, which unfortunately gave their superiors license to assign them to tasks beneath their abilities. Faced with uninspiring work, many chose to leave the firm or perhaps even the profession rather than to give up time with their children. But when I posed the idea of teaching a design studio, which would take me away from the office three afternoons a week for an entire semester, those same superiors were surprisingly accommodating. It was for me a profound recognition of the lack of family support in that firm, and likely others: Flexibility is tolerated, but only if it supports a “professional” endeavor. I took the teaching position while also maintaining my position and status in the firm. Predictably, some of my best project leadership and design work occurred during that time, invigorated by the additional layer of activity. I now know that having a child is equally if not more significantly invigorating. This is a very important point to employers and employees alike. Recommendation #4: As individuals, our lives are enriched through a variety of activities and experiences. Recognize that increases in the depth and/or breadth of experience can result in increased creativity, productivity, and happiness. But balance doesn't mean doing everything, or doing it forever. Prioritizing is key. With the clarity of hindsight, I see that my priorities have shifted dramatically throughout my career. In other words, how I’ve defined success and exactly what was included in “it all” have been redefined over time.

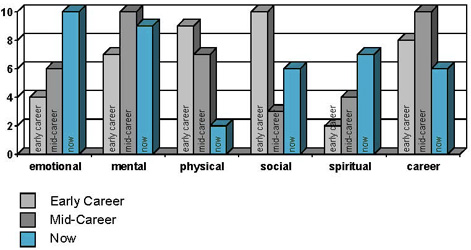

Early in my career, priorities included securing a design position in an architecture firm, getting licensed, socializing, and “bucking the system.” Mid-career was a time of serious focus on development, achievement, and advancement; a time of success and recognition. Working and teaching 70 hours per week was not only acceptable to me it was also invigorating. Today, my career has taken another dramatic shift. Following the birth of my son in 2003, I made the leap to self-employment and now enjoy a new type of balance. Working independently allows me to be selective about the projects I take on, allowing time for family and friends, lecturing and writing, and pro-bono projects that are dear to my heart. I know I am a better mother because I have a fulfilling career, and I know I am a better architect having the perspective of raising a family. Choices made during each of these phases aligned with my interpretation of success at the time. Recommendation #5: Recognize that priorities change over time. It’s ok to change direction to align with evolving priorities. Employees must communicate changes to their superiors, and employers must check in with their staff frequently. In the not-so-distant future, I believe this individualized approach will be the single most effective driver of firm success. As employers, we must value diversity of all kinds and endeavor to provide staff the flexibility to achieve balance in their lives. As employees, we should be ourselves, highlighting our individual strengths, values, and approaches. We can illustrate that various strategies can be employed to achieve the desired ends for our firms and for our clients. Clients will select the firms whose values and strategies (and egos) align with their unique needs. And as the number of women-led organizations and women-owned businesses continues to skyrocket, increasing numbers of our clients will be women. The more substantive story, in my opinion, is told by individuals: the mother and father architects, the wife and husband architects, the daughter and son architects, the runner and climber architects, the singer and writer architects, and all of us who are defining and achieving “balance” in our lives and our careers. Participants in our matri.ARCH.itect session heard stories from the moderator and panelists, but more importantly from their peers in the audience. There were many requests to repeat the session and to continue this valuable and timely conversation. In response, there will be an event during the 2008 AIA National Convention & Expo in Boston in May, with all new panel members and a new (less gender-specific) title: “Risky Business—Work/Life Balance”. We also established a blog as a venue to share stories and insights. We would love to hear from you … Recommendation #6: Share stories and insights with peers and friends, learning from the mistakes and successes of others, as well as gaining support and confidence to set your own priorities and your own strategies to achieve them. I did go to San Antonio to participate in the panel, although my daughter was still-born several weeks earlier. It was and is a pretty crazy time in our lives, but we go on with priorities yet again redefined. I still seek success, balance, and having it all, and I am doing it even as I write this piece. I value the ability to have allowed my career to take a break while I took care of myself and my family, and I appreciate having my career to give my heart a diversion from its recent sadness. It’s my balance and I wouldn’t have it any other way. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

Amy Yurko, AIA is a dedicated wife and mother. She is principal and founder of BrainSpaces, a consulting practice promoting brain-based considerations in the design of learning environments. Over her 20-year career, she has practiced architecture in large corporate firms and has held faculty positions at the University of Southern California and Illinois Institute of Technology. She is currently a member of the AIA Chicago Board of Directors, Chair of the Curriculum Design Sub-Committee for National AIA Continuing Education, National AIA liaison to the NAAB, and a Board member of the non-profit organization, “Schools for the Children of the World.” She welcomes comments, questions and conversation at ayurko@brainspaces.com.