| Novelty Hill’s Contemporary Winery Blends the Traditional and High-Tech

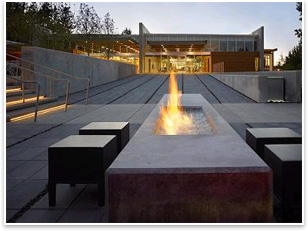

Novelty Hill’s new state-of-the-art winemaking facility in Woodinville, Wash., completed this summer, embraces the connection between the earth and the individual, from growing grapes through lifting a glass. The winery’s purpose—producing award-winning wines while promoting the grape’s ability to elevate the human spirit—is carefully reflected in the architecture and landscaping both inside and out. Two independent wineries, Novelty Hill and Januik Winery, share the new high-tech production facility and tasting room. Tom Alberg and his wife, Judi Beck, founded Novelty Hill in 2000. Alberg also heads the Madrona Venture Group, which invests in high-tech start-up companies. Mike Januik, winemaker for Chateau St. Michelle for nearly 10 years, crafts the exquisite wines for both wineries. The facility’s annual production capacity is 30,000 cases. “It was essential to show the connection between the earth and the wine, and the whole story of how wine is produced,” says Susan McNabb, AIA, project manager and project architect for the seven-person team of architects, interior designers, and landscape architects, including Alberg’s daughter, landscape architect Katherine Anderson, who all worked on the project at Mithun. Alberg and the architecture team wanted to illustrate the connections to the earth, vineyards, and nature in the structure through repeating patterns and blend both the traditional and high-tech along the way. Linear rows of grapevines and gleaming rows of fermentation tanks guided the shape of the building’s footprint and landscape. Parallel concrete walls and overhangs extend into the outdoor space and repeat throughout the terrain, where walls and terraces create a geometric rhythm in the landscape. In contrast to the solid, grounded concrete, walls of glass and resilient ipê hardwood bring warmth to both the inside and outside spaces.

Two-thirds of the building is devoted to the industrial aspects of manufacturing wine, including crushing, aging, and bottling, and Alberg wanted to reinforce this high-tech appearance. From the far end of the building, where the wine is crafted, to the front, where the wine is tasted, “the whole thing has a certain industrial look,” says Alberg. “It increases in sophistication and warmth as you go from one end to the other. What really grew out of our discussions was that this was a place where you not only taste the wine, but actually make it.” A corridor runs from the front entrance to the wine-making back of the building and ends in a deck enveloped by a canopy of trees. This second-story walkway is lined with large glass windows, where wine aficionados can look over the two-story production floor and the barrel room. Visitors can even step through the glass and onto a catwalk above the tanks for an increased sensory experience to hear, see, and smell the earthy aroma of winemaking below. The production floor features 27 gleaming steel tanks up to 15 feet tall, and the barrel rooms contain wine stacked in French and American oak barrels. Interesting spaces Beneath the banquet room is the cellar, lined with barrels and bottles of reserve wines from the Novelty Hill-Januik collection. The Treehouse and the Cellar feature banquet tables made from old-growth timbers reclaimed from giant fir and red cedar trees cut nearly a century ago. As with many Washington wineries, Novelty Hill-Januik grows their own grapes—in this case, on 300 acres—in the arid, desert-like eastern part of the state, then transports them over the mountains to western production facilities to be transformed into wine. Alberg sought to bring the atmosphere of the eastern slopes into the design.

The barrel rooms are built into the slope to maximize the natural cooling properties of the earth, as temperature control is necessary for wine fermentation. The building and outdoor spaces were oriented to maximize southern exposure. Daylighting studies informed where to position skylights to maximize natural light. The team also worked with arborists to preserve large heritage trees on the site. These natural forms cast shifting shadows onto the canvas of the concrete walls. Inside there is a sense of freedom in the large open spaces, high ceilings, and visual connections to the outside. “We wanted to be sure the architecture reflected the high quality of the wine,” concludes McNabb. Indeed it does: Both Novelty Hill-Januik’s wines and its architecture have made a stir in the Pacific Northwest. Their wines have won accolades and 90-plus ratings from wine guru Robert Parker, and the winery recently received the Seattle Design Center Northwest Design Award for Best Contemporary Design and the IIDA Northern Pacific Chapter's INaward’s Best in Competition Award for Hospitality. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design