Design West Studio a Study of Its City

Iowa State University satellite program looks at how design can teach students about the past

by Zach Mortice

Associate Editor

How do you . . . create a design studio that teaches students about its location’s architectural heritage through materiality? How do you . . . create a design studio that teaches students about its location’s architectural heritage through materiality?

Summary: The Iowa State University Design West studio in Sioux City, Iowa, is an adaptive reuse project that transformed a former steam boiler plant into a design studio that references the city’s architectural history and cultural heritage through its use of raw, industrial materials. It was developed through the Iowa Great Places program and celebrated its grand opening in September.

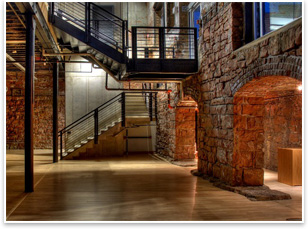

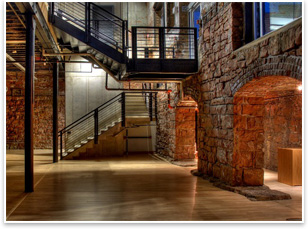

Plucked from the plains of eastern South Dakota, the quartzite stone that makes up the new Iowa State University Design West studio in Sioux City, Iowa, is an apt standard bearer for the city the design studio is intended to energize. This sturdy rock is rich in texture and expressive in color—in whites, grays, pinks, and reds. It’s seen in many of the area’s historic buildings. The rehabilitated quartzite interior and exterior walls of the facility display this variety in a warm, loose, natural design space in the best traditions of the city’s “quirky” architecture, says designer Nathan Kalaher, Assoc. AIA, of Sioux City-based M+ Architects. Like the richly varied quartzite stone that make up some of these structures, Sioux City hosts a wide variety of 19th- and 20th-century architecture styles, from Richardsonion Romanesque, to Italian Fascist, to the regionally ubiquitous Prairie School. Plucked from the plains of eastern South Dakota, the quartzite stone that makes up the new Iowa State University Design West studio in Sioux City, Iowa, is an apt standard bearer for the city the design studio is intended to energize. This sturdy rock is rich in texture and expressive in color—in whites, grays, pinks, and reds. It’s seen in many of the area’s historic buildings. The rehabilitated quartzite interior and exterior walls of the facility display this variety in a warm, loose, natural design space in the best traditions of the city’s “quirky” architecture, says designer Nathan Kalaher, Assoc. AIA, of Sioux City-based M+ Architects. Like the richly varied quartzite stone that make up some of these structures, Sioux City hosts a wide variety of 19th- and 20th-century architecture styles, from Richardsonion Romanesque, to Italian Fascist, to the regionally ubiquitous Prairie School.

Adaptive reuse design Adaptive reuse design

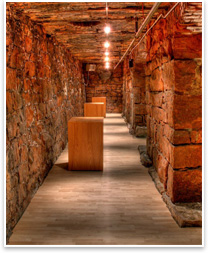

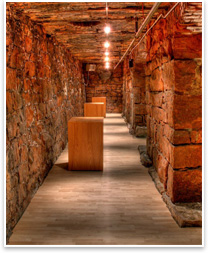

Design West is a 7,000-square-foot satellite program by the Iowa State School of Design that hosts classes on architecture, landscape architecture, urban and regional planning, interior design, and graphic design. Local and Iowa State students will both use the facility. Originally a steam boiler plant that heated adjacent buildings through a network of underground tunnels, the site for the studio is nestled into the city’s historic 4th St. District, a former commercial center and red light district that is now recovering from decades of under-use and decay with new waves of restaurants, bars, and boutique businesses springing up. This single story, stand-alone building is surrounded by three narrow alleys and a parking lot, and its lack of street frontage necessitated the use of its eye-catching 80-foot smoke stack as a key signage element.

Built in 1890 and nearly vacant for 80 years, time and the harsh weather changes of the Upper Midwest had taken a severe toll on the building. The lack of plumbing and electricity meant that subzero winters and blazing hot summers were never moderated. “Even though it was a utility building,” says Kalaher, “it didn’t have any utilities.” This seasonal freeze and thaw was especially damaging to the brick work of the quartzite walls. When the project began, Kalaher says “there was a foot of mortar dust on the floor.” Built in 1890 and nearly vacant for 80 years, time and the harsh weather changes of the Upper Midwest had taken a severe toll on the building. The lack of plumbing and electricity meant that subzero winters and blazing hot summers were never moderated. “Even though it was a utility building,” says Kalaher, “it didn’t have any utilities.” This seasonal freeze and thaw was especially damaging to the brick work of the quartzite walls. When the project began, Kalaher says “there was a foot of mortar dust on the floor.”

Cow town pride

The rehabilitation of the steam boiler plant was funded through former Iowa Governor Tom Vilsack’s Iowa Great Places program in 2005, which was created to invest in and invigorate the infrastructure and cultural amenities of Iowa towns and neighborhoods. Sioux City was selected as one of three pilot communities. As a co-chair of the Great Places Committee, Kalaher has been working with the program since its beginning, and has seen it capture the city’s imagination. “There were people with napkin sketches at bars and restaurants, and people talking about it on the street,” he says. “It was really taking place at the grassroots.”

The project’s task is to re-knit the urban fabric of Sioux City—to reunite the city with the Missouri River waterfront that forms the border with South Dakota and Nebraska, as well as to connect what Kalaher calls the various “investment areas” of the city, like the 4th Street district and the historic stockyards that were once the lynchpin of the area’s economy. The Great Places designation got the city $1 million, $537,000 of which was used for the design studio. The project’s task is to re-knit the urban fabric of Sioux City—to reunite the city with the Missouri River waterfront that forms the border with South Dakota and Nebraska, as well as to connect what Kalaher calls the various “investment areas” of the city, like the 4th Street district and the historic stockyards that were once the lynchpin of the area’s economy. The Great Places designation got the city $1 million, $537,000 of which was used for the design studio.

Design West is an urban laboratory dedicated to using Sioux City itself as a reference text for teaching students about architecture and design. Its intent is to decode the aesthetic appeal of this “cow town with an opera house,” as Sioux City is described in its Iowa Great Places submission materials. The opera house in question was the Peavey Grand Opera House, an ornate Second Empire theater with a double-tiered balcony and a gracefully arched proscenium. Though it caught fire in 1931 and had to be torn down, it was a potent symbol of the frontier town’s prosperity and rapid 19th century rise as a regional stockyard capital. Design West will give students an opportunity to investigate this quintessentially Midwestern small-scale cosmopolitanism.

Palette of stone Palette of stone

By maintaining the materials and original structure of the design studio, M+ Architects (who have worked on many adaptive reuse projects across the state) honor this history. In parts of the building where they could not save the original structure, they installed new structural elements, like stairs and a 23-foot atrium. In the studio’s below-ground level, Kalaher reprogrammed a steam tunnel into an art gallery, complete with five ground-level skylights fashioned from manhole openings formerly used to lower coal into the tunnel. In addition to the quartzite, the interiors are also composed of white brick and painted red brick. Hardwood floors, exposed ceiling ductwork, and a cantilevered stair complete the open, spacious floor plan.

This palette of raw, industrial materials, Kalaher says, was an affordable choice for a tight budget and a transparent way to get students thinking about the architectural heritage of their location. It’s also unassumingly hip for this tiny, Midwestern metropolis, or for any city, whether it has cows, an opera house, both, or neither.

|