Rodolfo

Acevedo, AIA Rodolfo

Acevedo, AIA

Summary: Rodolfo Acevedo, AIA, emigrated from Argentina 17 years ago with a degree in architecture. Upon arriving, he was unable to gain employment as an architect but was soon given a chance to work with JMWA in Boca Raton, Fla. To gain licensure in the U.S., he had to take additional college courses, go through IDP, and sit for the ARE. In 1998, he gained his architecture license and in 2002 became a principal with JMWA. On August 28, Acevedo broke ground on his new U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services building in Hialeah, Fla., and the following day he became a citizen of the U.S. Education: My degree is from the University of Córdoba, Argentina, and my degree is comparable to a BArch. Emigrating to the U.S.: When I immigrated to the States in 1990, I was already licensed in Argentina. I started working here about six months later as a print person. Back then, there were ammonia prints—bluelines. I couldn’t get a job as an architect because I didn’t have local experience and I didn’t know much of practice here, so those were good years to learn the practice in the States.

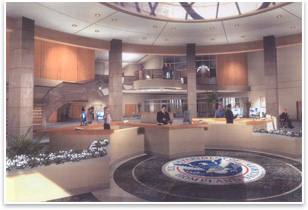

Proudest achievement: The coincidence of attaining citizenship and being awarded with the design of this building simultaneously. On breaking ground on the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Building one day, then becoming a citizen the next: It was a pretty awesome coincidence. I found out about it a month before, when I got the letter from Immigration. How did your experience inform the design? That’s an easy one, because there are so many things wrong from a design point of view and being an architect you can identify all those points in the inadequacy of the facilities. To get the opportunity to actually put them into practice is great. Some examples of the problems inherent in immigration facilities are: not enough room for waiting in long lines and having to wait outside sometimes, lack of parking, and even the conditions of the workers who are working there. You can easily understand why they are in a bad mood or very mean to people, because the working conditions are not ideal when it comes to lighting and even to the equipment, furniture, and facilities that they have to work with—or not to work with. Those were aspects that we were lucky enough to be able to address in the design of the facility. In addition to the program that we were given by the Department of Immigration Services, they themselves wanted to solve these problems from their end. They wanted to solve and improve the conditions of all their buildings. It was a requirement that this building be certified LEED®-Silver, and that is the reflection of where Immigration wants to go with this building. What do you think about diversity in the profession? Actually, I think it’s good. If we’re going to talk about our company, we’re about 50 people and half of the employees are from other countries. Most of them are Latin, like me, but we also have Haitians, Jamaicans, Asians. I think it’s great because they bring varied contributions that I believe have improved the practice and the service that we offer to clients—because our clientele is very diverse, too. I think it’s a reflection of the population here in South Florida with a heavy immigration influx, and that’s beneficial because there are a lot of candidates to interview and to hire. What should the AIA do to promote diversity? After all the exposure regarding my citizenship and this building and getting e-mails from people all over the world, architects from abroad don’t know that they can work in an architecture firm in the U.S. with the knowledge that they have and before getting a license here. I found out that they think that they have to get a license before they can do drafting or work for an architecture firm. Perhaps the AIA could make it more well-known to everybody that they could apply for some jobs without having a license. What’s next? We’d like to go after the next immigration building. INS has put out an RFP, and I think we’re in a good position to continue. |

||

Copyright 2007 The American Institute of Architects. All rights reserved. Home Page |

||

news headlines

practice

business

design

The path to licensure:

The path to licensure: